1.

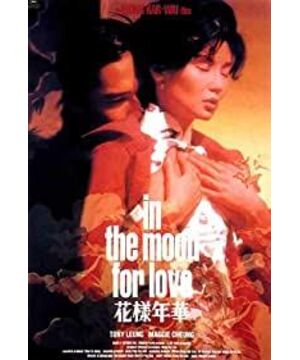

In the scrutiny of Western film media, "In the Mood for Love" is Wong Kar Wai's most perfect work. It almost uses a ritualized oriental charm and aesthetic performance to carry an impossible romance with a touch of sentimentality. Prior to this, there has never been a Chinese-speaking director who used such a symbolic style to present the Eastern style of love that is detached and unforgettable.

This is probably why the famous British film magazine "Vision and Hearing" listed "In the Mood for Love" as one of the 50 best films in film history in 2012, and it is also the only Chinese film on the list. Even picky French people praised "In the Mood for Love". In 2000, the "Cinema Manual" first selected the top ten of the year, and it was selected as the fifth; fifteen years later, the "Manual" again selected the best 250 in film history. The film, "In the Mood for Love" is the only Chinese film selected. Of course, it has been praised and occupies countless lists in the major Western film media, and almost no other Chinese-language film can match it.

However, for Wong Kar-wai, "In the Mood for Love" is a key turning point that is hidden and undisclosed. No matter in terms of video style or connotation, "In the Mood for Love" is completely different from his other previous films. And just after this film, Wong Kar-wai’s narrative interest and even expression thoughts have undergone a regrettable shift, from open to closed, from wandering to constant, from mysterious and unpredictable freedom to freedom. Reluctant to give up after thousands of times.

2.

The French philosopher Deleuze once divided film images into three categories in his film philosophy work "Motion-Image": perception, emotion and action. They respectively represent three different states of image expression. In his view, a movie can be composed of these three different types of images, or it can be developed around one type of image. Furthermore, he believes that between emotion and action, there is a special type of "micro" image, or a unique emotion expressed by the image, which he calls "Affect", that is, emotion. A critical state that is stimulated and surging out, but has not yet been perceived by the recipient. In other words, this is a state of diffusion in which emotions are floating in the "air" without belonging.

Deleuze believes that there are very few movies that really revolve around "affairs". He only cited Wim Wenders's "Alice in the City" as an example in the book. However, if he had the opportunity to watch Wong Kar-wai’s early films "Carmen in Mong Kok", "A Fei's Story", "Evil West Dux", "Chongqing Forest" and "Fallen Angels", he would most likely be surprised, because almost all of them can be Categorized as a "sentimental" movie. That's right, before Wong Kar-wai, there was no director in the history of film, and he made five films in one breath, all of which were diffused without touching the emotion of the recipient. From this point of view, Wang Jiawei in the 1990s was not only a master of romantic sentiment, he also became a practitioner of Deleuze's image philosophy without knowing it.

3.

In "Chongqing Forest", the two pairs of characters Jin Chengwu/Lin Qingxia, Liang Chaowei/Wong Faye are in a strange state: they get together, one of them is deeply attracted by the other, and constantly releases emotions to each other; But the other person is absent-minded, and his thoughts are always flying outwards pointing to those inaccessible people and things, and he has no intention of receiving the emotions of the people around him. So in the image space of "Chongqing Forest", such unowned emotions and misplaced feelings gradually diffuse like a smoke screen, and finally fill every virtual corner of the entire film, and the only thing they can't contaminate is in it. Of several characters.

Not only "Chongqing Forest", "A Fei's True Story", "Darkness" and "Fallen Angels", and even his debut gangster movie "Carmen in Mong Kok" are full of emotional signals that always miss the recipient. They are in the movie Shuttle back and forth in the space of the screen, crocheting a romantic world with the label of Wong Kar Wai. This is what makes him unique: in the nineties, he did not pursue emotional closure or create a happy ending, but persistently let the characters' emotions continue to drift elsewhere.

If we can say that from "Happy Together" we have smelled the tendency of some characters' emotions to intersect and close, then "In the Mood for Love" produced in the first year of the new century is a big turn of 180 degrees. From the very beginning, we discovered that what separated the two protagonists, Zhou Muyun and Su Lizhen, was their rational life state: they were married. In the process of the film, the two sides went from unfamiliar to familiar, from calm scrutiny to cuddling and reluctantly, emotions, thoughts and even eyes were constantly docking, resulting in a closed communication.

If the previous Wong Kar-wai didn’t care about the physical gathering of the two parties, and paid more attention to the directionless and purposeless dispersion of emotions, then starting from "In the Mood for Love", he showed the completely opposite intention: physical physical gathering and emotion The closed state formed by the docking became his repeated performance and prominent theme, and their separation and no longer intersecting became the most regrettable regret. From this moment on, he broke away from the state of "Deleuze's emotional image", and returned to the inner emotional narrative line of popular drama: physical separation is a kind of pain, and emotional separation becomes a sad ending. The infinite charm of the diffuse "sentiment" that was rendered in his original film was turned over in "In the Mood for Love" and became the "culprit" of unsatisfactory love, which is the root of all tragic elements.

4.

We cannot say that "In the Mood for Love" has fallen into vulgarity. There are still many moving love movies that are based on emotional communication and chemical interaction between the characters. But for Wong Kar-wai, this is a regressive transformation. He withdrew from his iconic or even deep philosophical uniqueness and returned to the human nature on the screen that we are used to.

What's interesting is that we can still see Wong Kar-wai's nostalgia for Wandering and Separation in "In the Mood for Love": Su Lizhen and Zhou Muyun suddenly began to play the imaginary situation in which their marriage partners seduce each other, and their thoughts, emotions and even personalities. They all floated out of their bodies, full of possibilities of intersecting and disjointing each other. But only a moment later, the raised souls of the two quickly fell back to the ground, returning to the two sentimental and affectionate men and women we were familiar with. Wong Kar-wai seems to be bidding farewell to his past self through such a setting: after all, the abnormal emotions that flashed by aura are instantaneous and short-lived, and after that what he wants to express is his heartfelt feelings with immutable and eternal meaning (this is "In the Mood for Love" The main theme of the sequel "2046").

With the change of the theme, Wong Kar-wai's video language in "In the Mood for Love" has also undergone a qualitative change. In order to stabilize the two main characters within their emotional frame and no longer drift around, he abandoned the erratic and fast switching handheld photography and exaggerated and highly rendering close-up wide-angle close-ups. He always maintains an elegant distance between the characters and the camera, and fixes them in the center of the picture by half-length close-up. This change makes the delicate and clear emotions the real protagonist of the image performance, but at the same time it obviously slows down the film's rhythm and leads it to an unavoidable monotony in the overall vision.

In order to make changes within the limited selection of framing, Wong Kar-wai began to use conventional slow-motion to express the characters' movements, and accompanied by the overflowing and exotic music. The incitement of the audience's emotions through music has eased the repetitive procrastination of the rhythm to a certain extent, but at the same time, the film is in danger of slipping into a music video with a vacant form and a lack of content. Such a series of problems caused by the change of aesthetic choice caused by the change of the content subject caused Wang Jiawei to sacrifice a means of expression that he did not commonly use before: symbolization. Su Lizhen’s dazzling variety of fancy cheongsams that are constantly changing is such a symbolic weapon: it does not even have a substantial connection with the storyline and the character of the characters, but symbolizes the meaning from a distance. An Eastern style of implicit emotional release, while visually enriching the expression of multiple changes in the sense of rhythm. The audience's attention shifted away from the scenes of the soundtrack which were actually inserted abruptly, and they were attracted by the renovated cheongsam fabric and the graceful female body. It has become a symbolic symbol of the feminine and feminine attitude of the East in "In the Mood for Love", and it hits the G-spot of the pleasure of western audiences with "Orientalism" in a very counterpoint manner. The latter generalizes it as “Oriental colors”, and selectively ignores the signs of the film’s inner theme, and the traces of the separation between the characters’ personalities and identities—no one will ask why a company’s typist wears them. If you can afford such many styles and well-tailored cheongsams, everyone will only be dragged into the fantasy of Asian women by the soundtrack costume display.

This is Wong Kar-wai's cleverness. He is always clearly aware of the technical effect of seducing the audience with just the right formal charm: it can have a symbolic connection with the content of the film without directly being involved. It's like two stones will not melt and become one when they are boiled in boiling water, but it doesn't matter, they only need to look like the same thing.

5.

The Western media touted "In the Mood for Love" is more derived from the fictional imagination of visual aesthetics with oriental traditions. But for Wong Kar-wai, "In the Mood for Love" is a sharp turn in the direction of inner creation. Since then, although he still worked hard to maintain the unique characteristics of the form, the inner character of the characters in the film-whether it is Zhou Muyun in "2046" or Nora Jones in "Blueberry Night", or It's Ye Wen in "The Great Master"-no longer the "love ronin" who does not ask the results but enjoys the process, does not close emotions but is open to release emotions. Instead, it turns into a "servant of love" who is obsessed with a certain emotion and never gives up. This process of turning from freedom to tradition and from open to closed is really embarrassing.

And "In the Mood for Love" is just such a proclaiming work at a turning point: the wandering and flying of people gathering and dispersing gradually fade away, and the separation of the physical body of consonance becomes the main axis. It creates a romance that is tightly locked by the mind in a way that the form is greater than the content, and the sensation is more than the mood.

As the years go by, a person may not be able to stay on the move forever. And Wong Kar-wai's filming of "In the Mood for Love" at the 42-year-old node may mean the maturity of his spiritual age (senility?) and the passing of his youth impulse.

View more about In the Mood for Love reviews