Written shit is not, but still have to save a file. Make-up work in the middle of the night is not advisable.

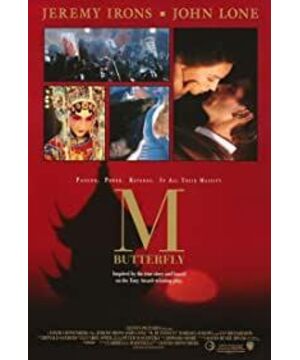

If The Butterfly King, adapted from the original work of Chinese American Huang Zhe Lun, has inevitably been stained with the traces of staring at the "Other" in the East from the subjective perspective of the West, then its Canadian director David Cronenberg Under the second creation of Grid, it has obviously become an indescribable hybrid of reconstructed "Oriental symbols" under the blessing of images.

The film sets the mythology around 1968, the year the worlds collided. At that time, whether in the hinterland of Eastern Europe shrouded by the Iron Curtain, in the industrial cities on the banks of the Great Lakes in northern America, or in Paris, the holy land of humanism, a left-wing wave heralding the wind of innovation was sweeping the world. And in the far, mysterious East, a movement that sees the beginning of the dragon but not the end is at its climax. Middle-class youth in the West could never imagine how destructive and radical the movement was, and their fantasies about revolution and the East were filled with propaganda posters and red treasure books printed in Fat Song script. It was not until the release of Italian director Antonioni's documentary "China" in 1972 that the mystery of the ancient country was solved. A few years later, with the political disarmament of that movement and the opening of the diplomatic sphere, three and four generations of reflective films were able to meet Western audiences. However, whether it is the ideological propaganda before 1976 or the scarred films after 1978, for most Western audiences, the spectacled visual symbol system of the movement is only constructed from the appearance.

Just like The Butterfly King, The Last Emperor, and The Chess King, which are mistakes made by films that look at China from an external perspective, the scenes involving that movement were undoubtedly over-masked and stylized by the artist according to his own wishes. In the film "Mr. Butterfly", the director used the eyes of the protagonist Gao Renni to reproduce many scenes of communist China in the mid-1960s. But we can clearly find that the shots of the daily life of the Chinese people in the film undoubtedly draw on the content and composition of Antonioni's "China". In addition, in a drama that uses the "broken four olds" as a metaphor for the change of the times, we can find several typical impressions about the Cultural Revolution are figuratively pieced together by the images: the burnt costumes, the people dancing the Loyalty Character Dance. Female Red Guards, the crowd holding up the red treasure book and the portrait of Mao Zedong, as well as the stinky old nine and the actors who were "flying" by the young Red Guards with wooden signs marked with black crosses.

These familiar scenes have already been presented in "The Last Emperor" and "Farewell My Concubine", but for these two films, the appearance of such scenes is completely in line with the narrative structure and the inner motivation of the characters. In "Mr. Butterfly", the description of the scenes of the Cultural Revolution has completely become a spectacle-like, acrobatic display, an interpretation of the "violence and barbarism" of the revolution.

This hybrid presentation that breaks time and space also appears in the official residence of Song Liling, played by Zun Long. The story of the film begins in 1964, eight years after the end of the socialist transformation. During this period, almost all courtyards in Beijing were taken over to the public and re-divided as dormitories for major enterprises and institutions. rented to workers. However, in the film, Song Liling not only monopolizes the meticulously maintained courtyard, but also owns a southern mother who seems to have walked out of the post-war movies in the 1940s. Neither the so-called "house attendant" nor the whistleblower sent by the organization seems to be able to tactfully explain the reasonable meaning of the mother's existence in the film. Together with Siheyuan and Song Liling's cheongsam, which symbolizes tradition and submission, she forms the form and appearance of the director's interpretation of "ancient and mysterious" China. This set of signifier symbols corresponds to the tradition and stability of the ancient oriental country in the director's mind, while the strange show about the Cultural Revolution points to disorder, chaos and the externalization of Gao Renni's inner state of mind.

Perhaps the director does not necessarily want to present a contemporary China full of stereotypes in such a film that deconstructs the mysterious East, but the tone of the film with romanticism and modernity undoubtedly keeps him away from realism and historical facts, and internalizes the storms of the times For the inner waves of the character. So we were able to see such a reconstructed "contemporary East" in the film very coincidentally.

View more about M. Butterfly reviews