big phantom

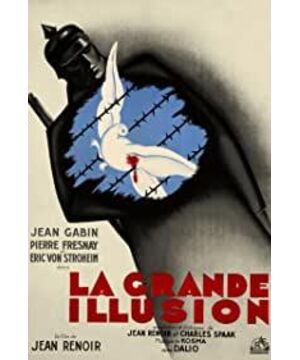

Grand Illusion, 1937

Among other achievements, Jean Renoir's "The Grand Mirage" influenced two later famous film sequences. In this 1937 masterpiece, we get our first glimpse of the tunnel-digging escape in "The Great Escape" (1963) and the Marseillaise sung to anger the Germans in "Casablanca." Even the details of digging the tunnels are exactly the same - prisoners hide the excavated soil in their pants and shake it out when they go to the playground.

But if The Great Phantom was just the inspiration for some later films, it wouldn't be on the list of so many great movies. This is not a film about a prison break, nor does it take a chauvinist strategy, it considers the disintegration of the old order of European civilization. The notion that gentlemen on both fronts follow the same code of conduct may forever remain a sentimental hallucination of the upper classes. Whatever it was, died in the trenches of World War I.

The captured French nobleman Colonel Boisdieu told the commander of the German prisoner-of-war camp von Hauffenstein: "Neither you nor I can stop the passage of time." escaped from the German castle, and ran to distract the guards. He forced the German commander to shoot him reluctantly, and the two said their last words before his deathbed. Boisdieu told the German, "I didn't know that being shot in the stomach hurts so much." The German said, "I'm aiming for your leg." He almost burst into tears. Shortly afterward, Boisdieu said: "For civilians, dying in war is a tragedy. But for you and me it's a good way to get out."

What Boirdieu understood, and what Hauffenstein would not admit, was that the new world belonged to the common people. When the gentlemen of Europe declared war on each other, the world moved into the hands of others. The title of Renoir's film, The Great Phantom, refers to the idea that the upper classes can be detached from war. The German commander could not believe that the prisoners of war he treated as guests would try to escape. After all, they promised not to.

Playing the commander is Eric von Stroheim, one of the most famous performances in film history. Even many people who haven't seen the movie will recognize the stills of the wounded ace pilot von Hauffenstein, his body held tightly by the braces on his neck and back, his eyes squinting through his monocle. . De Boisdieu (Pierre Fresna), from an old noble family, is a pilot who was shot down by von Hauffenstein himself in the war. The other two main characters are also French prisoners of war: Marshall (Jean Gabin), a worker, part of a rising proletariat, and Rosenthal (Marcel Darryl). O [Marcel Dalio]) is a Judas banker who, ironically, buys a castle that the Boirdieu family can no longer afford. The film was made as the clouds of World War II were gathering, and it used these characters to show how the themes of World War I would tragically deteriorate further in World War II.

Renoir's message was so sharp that when the Germans occupied France, the first thing they confiscated was The Grand Mirage. Propaganda Minister Goebbels publicly declared it "Public Enemy Number One" and ordered the confiscation of all original negatives. The film's subsequent history could be made into a film like The Red Violin (1998), the copies of which surreptitiously cross borders again and again. For many years, it was believed that the negatives were destroyed in an Allied air raid in 1942. But according to Stuart Klawens' report in The Nation, a German film archivist named Frank Hensel singled out the copy, and then a Nazi in Paris The officers shipped it to Berlin. By the sixties, when Renoir was overseeing a compilation of "restored" copies, no one knew anything about the original negatives. His material came from the best of the surviving cinema prints. As a result, the version the world has seen so far is a bit scratched and blurred, with awkward subtitles embedded in it.

At the same time, the original copies fell into the hands of the Russians occupying Berlin, and they were transported to the Film Archive in Moscow. Kravens writes that in the mid-1960s a Russian film archive exchanged copies with an archive in Toulouse, France, including the invaluable "The Grand Mirage." But because many other copies survived, and the original negatives were not believed to exist, it took another thirty years for these negatives to be considered treasures. All of the above means that the now nationally restored version of The Great Phantom is the best it's been since its premiere. The new subtitles, by Lenny Borger, have also been greatly improved – “cleaner and clearer”, says critic Stanley Kaufman.

This copy feels like a whole new movie. What we have is a refreshing version that highlights Renoir's visual style and his excellent technique for using subtle camera movements to capture longer passages without cutting shots. In the paintings of his father, Auguste Renoir, the camera gently guides our eyes through composition after composition. There is a quiet luxury in Son's films, no punctuation between frames, no sudden insertions, only smooth unfoldings.

At the beginning of The Great Phantom, we see Hauffenstein in a mess of German officers. He shot down two French planes and gave the order: "If they are officers, invite them to lunch."

Marshall and Boisdieu were later sent to a prisoner of war camp, where they met Rosenthal, who was already a prisoner. The food parcels sent by the Rosenthals did them a great favor, and they usually ate better than the jailers. There are also passages dug tunnels and the famous amateur singer concert scene. All fell silent when the prisoners saw a man in a woman's attire come out, they had not seen a real woman for too long.

The digging of the tunnels was interrupted because the prisoners of war were moved elsewhere. A few years later, all three main characters are sent to the POW camp in Winterbourne, a castle with impenetrable walls. Hauffenstein, unable to fly due to a back injury, volunteered to be commander of Winterbourne in order to remain in the army. He is strict, but also impartial, still deceived by ideas like class loyalty.

A man who was bewitched by romanticized notions of chivalry and friendship, Stroheim made an indelible impression in these scenes. His performance was touching. It's a collaboration between two great directors, one from the silent era and the other emerging as a master of sound. His performance was even better than it looked: audiences thought Eric von Stroheim was a German, but his origins were always shrouded in mystery. Born in Vienna in 1885, Stroheim was already working with DW Griffith in Hollywood by 1914, but when did he immigrate to America (and add a "von" to his name)? Renoir wrote in his memoirs: "Stroheim could hardly speak German. He had to learn his dialogues like a little boy learning a foreign language."

The escape from the castle prison, which leads to a touching end-of-day farewell between Boisdieu and Hauffenstein, is one of the most moving scenes in the film. Then we joined the worker Marshall and the banker Rosenthal as they tried to walk across German territory to another country. A farm widow offers them shelter, and she sees security in Marschalle. It is also possible that Renoir is here to tell us softly that the real class connection between the antagonists can only take place between the workers, not the rulers.

Jean Renoir was born in 1894. I rank him as one of the half dozen greatest directors, and his "Rules of the Game" (1939) is even more acclaimed than "The Great Phantom." He fought in World War I, then quickly returned to Paris and entered the film industry. In his best films, every shot shows observation and sympathy for the character. Almost none of the camera positions are chosen purely for effect, without first thinking about where the best position to observe the character is.

Renoir went to America in the 1940s and made several Hollywood films, notably The Southerner (1945) written by Faulkner. In the 1950s he started independent production with The River (1951), an adaptation of Rumer Godden's Calcutta story. During his long retirement he has been the object of young filmmakers and critics who feel that Renoir is as sunny as his grandfather in one of his father's impressionist paintings. Renoir died in 1979. He would have been very happy to know that even then the original negatives of The Grand Mirage were waiting to be discovered in Toulouse.

(Translated by Zhou Boqun)

View more about La Grande Illusion reviews