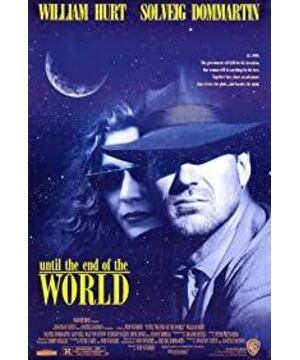

till the end of the world

Bis ans Ende der Welt (1991)

Director: Wim Wenders

Writers: Wim Wenders, Peter Carey, Solveig Domartin, Michelle Amiriad

Starring: Solveig Domartin, Chick Ortega

Genre: Drama / Science Fiction

Country/Region of Production: Germany/France/Australia

Language: English/ French/ Italian/ Japanese/ German

Release date: 1991-09-12

Wenders often calls "Until the World's End" the "ultimate road movie," perhaps not even realizing it was such an apt description. The film was necessarily, and always will be, the most prolific and ambitious foray into the road genre that has dominated Wenders' career, and it's his last road film in years to come. The original 158-minute abbreviated version of "Until the End of the World" was a box-office hit, and soon it was seen as a cursed movie, one of those mutilated films that shined in its own right. Although it was covered up, there was still a glimmer of light left. And the 287-minute director's cut is a true masterpiece.

Wenders revealed that under the contract, the length of the film was limited to two and a half minutes, but during the editing process, he realized that this was almost impossible. He asked production partners to allow him to edit the longer version and split it into two parts. The request was denied, and Wenders did what he thought was "the smartest thing I've ever done in my life." He secretly saved the two developed director's cuts and Super 35mm negatives, and paid for another to be developed. The full-length film competes with the abridged version, which he now calls the "Reader's Digest theatrical version."

In the early 1990s, director's cuts were not as common as they are now, but Wenders' vision led him to believe that longer versions would eventually come out. A few years later, he did, and as early as 1993, he brought his masterpiece, which he polished for nearly five bells, to museums and events for screening.

Before the idea for "Until the End of the World" sprouted in 1977 and 1978, Wenders traveled to Australia on a whim and stayed for several months. He recalled, "I was fascinated by the beliefs of the local Aboriginal culture, dreamlines and songlines. When the whole country was overwhelmed by the way of casting words and notes along the way, weaving dreams, also known as the map of songs, he began to work on a sci-fi script about the end of the world, and the appearance of the world will remain in the remote Australian desert. "After that, Wenders combines his ideas with a mythological retelling of The Odyssey, in which Penelope, anxiously awaiting Odysseus, decides to embark on a quest for a husband.

During filming, Wenders teamed up with his muse and actor Solveig Domartin, screenwriter Peter Carey, and filmmaker Michelle Amiriad to complete this constantly revised stories and scripts. We can also glimpse the shadows of these artists in the film-Ameliad's smooth genre experimentation, Domartin's female perspective, her figure and voice add a playful tenderness to the film, which is in Wenders Rarely seen in previous works, we can also see some literary influences on the film in the final film, such as Bruce Chatwin's "The Map of Songs", which introduces the Australian Aboriginal people. Song culture, where songs connect dreams and land; and the dystopian and existential esoteric romance of the missing in Paul Auster's In the Country of Last Things story.

After the success of "Texas, Paris" and "Under the Berlin Sky", Wenders finally had the confidence and capital to embark on this ambitious project - spanning 20 cities, 9 countries, 4 continents, and the production cost of 2400 It was one of the few big productions in the European film industry at that time. The new film is heavily influenced by the themes of the first two works, each of which represents a juncture in Wenders' career: "Paris, Texas" is perhaps his best portrayal of America, a presentation he has been obsessed with all his life; "Berlin" Under the Firmament presents a gloomy, isolated Berlin run by imperfect angels that feels like his German swan song. (Though the box-office flop of "Until the End of the World" followed, he shot the now often-forgotten sequel to "Under the Berlin Sky", 1993's "So Far Away"). These films freed Wenders: the road ahead of him was wider than ever.

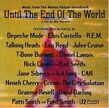

You can feel this expanse in the places that Till the End of the World travels every minute and every second, a kind of apprehensive awe that the film holds for the vastness of the world. Remarkably, Wenders invited 20 of his favorite musicians and bands from around the world to sing songs they imagined they would play in 1999, and nearly all accepted the challenge, Wenders The songs were eventually put together into an era-defining rock soundtrack that only appeared in abridged versions of exotic scenes, and could be heard in full director's cuts. Music and imagery have equal status, and together they render the atmosphere of the film. At the same time, Robbie Muller's colorful and idiosyncratic photography blends a variety of techniques and styles - film noir gloom, urban landscapes, natural serenity, classical elegance, and technically blurred pixelated images. Wait. Wenders was one of the most important directors of the early 1990s, but the sternness and compassion of his work also brought to mind a stereotype of the German artist: spectacled, head-to-toe black. (That's not entirely true.) But To the End of the World feels like the hand of a free creator, working at will in a new and free world.

During filming, Wenders told the Los Angeles Times, "It's not a sci-fi film. It's a contemporary film, and we're going to be a lot more free to set the story 10 years from now." That's not the norm. The freedom, so forward-looking, that the characters in the movie drive cars with navigation, albeit a different kind of navigation than today's GPS. "Until the End of the World" was filmed in a time when computers were only just getting commercialized, yet the film was able to accurately demonstrate the use of search engines and our ability to locate and track people through digital footprints. Interestingly, even the story of the film The frame — an Indian satellite that slammed into Earth on the turn of the millennium, cutting off all electronic communications and sparking a global panic — is also similar to the 1999 “Year-Year-Old” (Y2K) scare, when many believed The Millennium Bug will bring this technology-dependent planet back to the Stone Age.

Wenders is able to interpret the present through the use of an era close to the present. The world in 1990 has changed from a few years ago, especially for the German director. The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 brought the era of the Iron Curtain and the Cold War to an end, ushering in a civilization that was no longer held back by borders. (Originally, the idea of the fall of the Berlin Wall appeared in the storyline, but by the time Wenders finished filming, the Berlin Wall was a thing of the past.) Wenders said at the time: “History and technology are advancing at And human behavior, everything." This sentence may also confirm the grotesque and rich tension of the film, Wenders imagines the future in a strange new era, like a wonderful dream. But he also tells us that in such a fearless new world, there are seeds of self-destruction buried, which is another reason why this movie is the ultimate road movie – it leads to the end of the road.

The story in the abridged version and the director's cut is almost the same, but for Wenders, more important than the story itself is the point of view and rhythm he chooses to tell the story. There's a breathless depression lurking in the lighthearted international espionage genre, as we see at the beginning of the film: Claire wakes up at a night-lit party in Venice, wandering aimlessly through the colorful The room (reminiscent of the ingenious color space of Godard's road film Pierrot), people are either drunk or dance until dawn, the background music is "Sax and Violins" by Talking Heads, and the halo is delicate The messy, futuristic and shiny clothing exudes a charming atmosphere of decadence and depravity.

After Claire left the party, she took a rambling boat ride through the canals of Venice (a scene perhaps inspired by Lucchino Visconti, the great film poet who filmed historical decadence), found her car, and then our mistress was stuck On the way from Venice to France (traces of Godard's "Weekend"), she decided to take a detour through the forest. Then, she travels through stunning scenery along the way, off the beaten track (like a John Ford or Anthony Mann western). In these first shots, Claire's encounters are lifeless, her restlessness prompting her to find an exit. She has no destination, she is a wanderer who just wants to keep walking. (Claire took off the Anna Karina-style wig at the back, revealing the long blonde hair, like Brigitte Bardot in "Contempt", here, Godard's traces are very obvious)

As often unfolds in Wenders' work, the aimless wanderer meets the purposeful wanderer. In a crowded and chaotic shopping mall at the junction of Saint-Etienne and Lyon, Claire first met Sam Farber by a row of TV phones. Claire's final obsession with Sam Farber and the ambiguity of the two during the trip made her understand that there is something Wanderers hit the road with a clear purpose. For Sam (who begins by calling himself Trevor McPhee), the long trek from city to city, country to country, is just the face of this deep journey: he robs his father, Dr. Henry Farber, of The high-tech camera developed by the camera can record the photographer's brain waves and the images generated in the brain. Finally we learn that Henry and Sam are trying to restore sight to Sam's blind mother Edith using brain waves. Sam traveled the world recording images of friends and family, which he then projected onto Edith's brain through his nervous system in his father Henry's secret laboratory in Australia. In other words, it's a journey to the brain.

In order to make the plot unfold smoothly, Wenders created another unique, intertwined, loose story line. When Sam first appears on camera, we see him being tracked by a mysterious bounty hunter, Burt, and then by Claire, who has hired a private investigator named Phillip Winter (played by Rüdiger Vogler, Vogler Once again playing the role representing the director himself, however, the film has such characters hidden everywhere), Phillip also tracks Claire and Sam, and soon after, Claire's ex-boyfriend Eugene also joins the tracking game, Eugene I'm starting to write a story about Claire, which is narrated by the film's narration, and also determines the direction of the film from time to time.

Does it sound confusing? That's right. Wenders likes to eclectic elements of various genre films, while taking away the pleasure of watching genre films, he tells us bluntly: he did not choose the routine of genre films. The ruthless bank robber in "Until the End of the World" is actually generous and easy-going; the fedora-clad detective and bounty hunter are actually soft-hearted; even Eugene, chasing the lover who left him halfway, I don't really care if I hold a beautiful woman. All are trapped in the characters they long to get rid of (in Sam using a fake name and Claire wearing a wig). The film is slow-paced, and the plot is driven not by crisis, suspense, and mystery, but by fragmented emotions. In the second half of the film, where everyone ends up in Australia, it's more of a reunion of old friends than the film's dramatic conflict.

Wenders’ succession of cinematic metaphors also adds to the illusion of the film itself, which deepens the artificiality of the world and makes it overwhelming. It is clear that Wenders is immersed in the despair he has created, the millenarian despondency of a dead end. The entire film is a collage of metaphors, and each of Claire and Sam's journeys carries its own aesthetic metaphor. Chase in Tokyo is reminiscent of the works of Samuel Fuller and Kiyomizu Suzuki; French gangsters feel like characters from a Jean-Pierre Melville movie; Claire and Sam copy The scene where they come together is very much like the protagonist of Hitchcock's "Thirty-nine Steps"; in the second half of the Australian outback, the existentialist psychological drama of struggle and despair can be seen as Bergman's The combination with Antonioni (Jeanne Moreau, the heroine of Antonioni's "Night", and Max von Sydow, who has participated in more than a dozen Bergman works, two veterans of the film industry, also in the movie. perform).

"Until the End of the World" feels like the work of a director who is obsessed with picture and sound. The flood of sound and picture makes it need a little adjustment - interestingly, this adjustment also includes a film tribute. In Japan, Claire and Sam board a train that goes nowhere and end up in a remote inn in the mountains, where they are tended by an elderly couple, who are each ordered by Yasujiro Ozu's film. The unforgettable Kasa Zhizhong and Miyake Kuniko play. Sam nearly went blind from using his father's camera, and Claire treated him with herbs during this time. The rhythm of the film slows down, the frame is simplified to two basic shots and the main shot, and the background is filled with the sounds of nature. In fact, Wenders uses Ozu to get out of the hustle and bustle of the modern world.

Wenders believes in the healing power of art as well as its potential destructive power. Wenders' father was a surgeon, and when Wenders was young, he faced the choice of being a priest or a doctor. To a certain extent, "Until the End of the World" can be understood as an attempt to combine sound and vision with moral meanings. At first, Eugene writes, he resumed prayer at home alone shortly after Claire left him, "as I have always been, hesitant at first, but realized what it means to pray." He added, "It was this calmness that led me to my first novel, in which Claire was the protagonist." It is the porch of narrative mirrors, surreal and instructive: Claire evokes Eugene's introspective novel, which in the film In the end, the novel also rescues Claire from her addiction to images.

Although Wenders considers himself a Christian activist, the morality in his films is not strongly religious, but rather simple and unadorned: truth, beauty, and healing are not found in doctrine, but rather It is in the simplest and most basic things that are the most sacred. Sam relaxes listening to the singing of African Pygmy children, which his mother recorded many years ago. In the second half of the film, Aboriginal Australians use singing to find their land and preserve their culture. Compared with the dazzling variety of technological equipment, different languages, and postmodern hieroglyphs in the first half of the film, the second half is the animist and oral side of the film.

The general framework of "To the End of the World" -- a man and a woman going from country to country, continent to continent, to film footage that eventually devoured them and nearly took their lives -- this It's a metaphor for filmmaking, and it's a metaphor for the making of this film. Wenders prefers to shoot segment by segment, in part because it allows him to improvise certain scenes in rough terms, which means that the form and structure of his film images often bear the imprint of reality. . Of course, for road films, this technique is perfectly normal: the process of filmmaking mirrors the journey on the screen; but it also means that the film expresses a change in the creator's mood, as Wenders' earlier works, such as "Alice in the City" (1974) and "King of the Highway" (1976)—both intimate stories about the ever-changing chemistry of disparate individuals, the changes are subtle, the narrative is subtle. But "Until the World's End" is another road movie, not only because of the scope of the journey, but also because of the director's bold idea: in addition to showing the relationship between the characters, the film also explores the artist and the future, and the relationship between the planet. relation.

This makes the Xiao Shu sense of the film more tragic and prophetic at the end. Claire and Sam end up clinging to Henry's portable device that records and replays their dreams, and they're addicted to these mobile devices. They concentrate, stop talking, and sit apart -- a sight that's very much like people's iPhone addiction these days. (Claire finally collapses when her device runs out of battery, which is distressing.) The simple grimness of these scenes contrasts sharply with the film's subsequent metaphors and optimism, as if the work itself has grown from the first four hours of overflowing color, movement, and music. pulled out.

The variety of styles and forms throughout the film give Wenders' film the air of a student's work. In the second half, the footage is mostly digitally converted high-resolution video images of people's brains, which are blurred fragments of nightmares. Interestingly, "Until the End of the World" was one of the first films to use high-resolution imagery on a large scale, but Wenders didn't care about its eye-catching clarity and resolution, but about the fluidity of the image— He adjusted the pixels and lines to present the feeling of abstract and flowing oil on canvas. This is a completely different attempt to describe dreams in previous films. This effect is both beautiful and disturbing. It is a flowing runoff in the image world. , the director called "the destruction of visual culture".

We often talk about finding the self, and it’s a cliché about the traveler: journeys ultimately lead people to self-awareness, and that’s what Claire and Sam found in Henry’s camera rig: a gateway to their innermost being. Entrance. And that's devastating in Wenders' setting, these devices mirror themselves, and they're stuck in self-indulgence. At this level, Wenders left his most important and most cautionary predictions for last: if the promises of technology and the road, and of course, the film itself, were fulfilled; if all the doors of perception were opened; if In the end, in the journey of self-discovery, is there anything but numbness and despair? What if the destination is more dangerous than the journey? What if the end of the road is also the end of our dreams?

View more about Until the End of the World reviews