Aschenbach's eventual death is also the inevitable outcome of Lacan's dilemma of the subject—"an idealized voyeuristic-sadistic sexual relationship, a personality that can only achieve self-realization in suicide".

1. Introduction: Plot overview

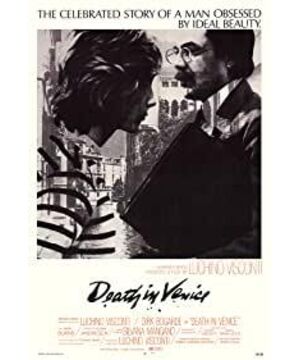

In 1971, the famous Italian director Visconti was diagnosed with cancer. After learning that he would die soon, he decided to make a film to express his thoughts on art and lament about life, so he chose German writer Thomas Mann's novel "Soulbroken Venice" as the blueprint, and shot "Soulbroken Venice". Broken Venice movie.

The film tells the story of the famous German composer Professor Gustav Asenbach, who just experienced the pain of bereavement, came to Venice for a vacation and wanted to take advantage of the beauty of the water city to soothe his mood. But all the scenery evoked were more sad memories. The longing for his wife and daughter who died early and the heat wave in Venice attacked him, and he could only continue to work on his own while struggling. It wasn't until one day that Asenbach met Tacchio, a beautiful young man in a hotel, and his face like a Greek statue made him tremble.

Asenbach's reason forces him to leave Venice, but before the train starts, he finds that his luggage has been sent elsewhere, so this becomes an excuse for him to return to Venice and to Tacchio. However, at this time, the city of Venice has been shrouded in plague, but the officials deliberately blocked the news. When Asenbach gradually discovered this astonishing crisis, he did not panic like others and wanted to escape as soon as possible. On the contrary, in order to take a look at Tacchio, he followed Tacchio in this dead city like a ghost all day long, willing to dye The plague killed Venice in Venice.

At noon on the day Tacchio was about to leave Venice, Asenbach sat on the beach and stared at him. Tacchio's flirting with his companions made Asenbach thirsty, so he got up to stop it, but collapsed on the beach exhausted, and his life ended. At this time, the young man slowly walked into the ocean, turned around and pointed into the distance, the perfect figure was like a Greek god slowly rising from the water.

2. The pain of losing a daughter: Oedipus complex and traumatic memory

When pursuing a sexual object, most children choose their mother as the object of their first sexual impulse, which is called the "Oedipus complex". A large part of the guilt that neurotics often feel guilty about comes from the Oedipus complex - "There is no neurotic who is not Oedipus [1] ". Freud thought: "Children often take their father or mother as their sexual object. The father loves the daughter more than the son, and the mother loves the son more than the daughter. The child also responds accordingly. If the son wants to occupy the father's place, if The daughter wants to take the place of the mother. The pleasures of these parent-child and child-child relationships are not only lyrical, but hostile as well..." [2]

In the movie "Breakthrough Venice", the metaphor of Oedipus complex is more obvious. In the film, Visconti shoots a lot of scenes about the seascape (Figure 1), and in the context of psychoanalysis, the seawater is interpreted as the mother's breast - silent, large and joyful. The permanent loss of the maternal breast created a traumatic memory at the bottom of Asenbach's heart, but this trauma was repressed, repulsed, and never revealed to consciousness. Asenbach transferred his mother's sexual urge to his daughter, and her daughter's death was undoubtedly the trigger for his trauma. "We call an experience a perpetual disturbance of the distribution of the effective faculties of the mind which, for a short period of time, causes the mind to be stimulated to a degree of the highest degree, so that it cannot seek adaptation in the normal way. The experience is traumatic [3] ", under the strong psychological impact, the repression cannot restrain the emergence of traumatic traces, so his adjustment mechanism is out of balance.

Or to put it in Lacanian terms, in the first half of Asenbach's life, his libido was placed on his daughter, so he would put her daughter's picture in front of the mirror, and whenever he looked in the mirror, At the same time, he will also see the image of the daughter (Figure 2), the "other" of the daughter is always in his own formal structure. And when his daughter dies, this other in the mirror becomes Tacchio, the new transfer object of his libido - Tacchio's perfect face is the best symbol of a mother's breast. And the daughter/Tacchio is not only the other. Asenbach's narcissistic identification with the self in the mirror is also the "formal fixation" implemented by the self to the object. The self is the other, and the other is the self. There is a double identity relationship between Asenbach and Tacchio, as Raymond puts it - "The older man plays the role of the boy's mother, and that's how he identifies himself, he can be like His mother treated the boy the way he did." [4]

3. Pursuit in the dark: lust and double peeping

Freud attributed neurotic symptoms, faults, dreams, the growth of personality, the creation of culture and civilization, and the driving force of human social development to sexual instinct, and "Soulbreak in Venice" well supports this point of view.

The original Asenbach was a very sexually repressed individual. Generally speaking, a normal musician would be delighted and excited if he met a muse who could inspire him, but Asenbach, who had just met Tacchio, was always ecstatic. It is to avoid Tacchio subconsciously. When he met Tacchio in the elevator, Asenbach just lowered his head without saying hello to Tacchio at all, and even had the idea of escape from Venice. He didn't dare to get close to Tacchio, and just followed Tacchio's figure in the dark, traveling all over Venice. This sexual repression is also manifested in the language of the lens. First of all, the scenes shot from the perspective of Asenbach are seen from corners, railings, etc., not directly from the human eye (Figure 3). This imprisoned subjective lens is the embodiment of Asenbach's closed mind. Secondly, there are many scenes shot from the mirror in the film, such as the dialogue scene between Asenbach and the hotel manager and the scene where Asenbach leaves the prostitute's room (Fig. 4), which makes the whole space show a feeling of infinite extension, In this sense of extension, a kind of subject depression will be induced in reverse, showing the isolation and occlusion of the subject in the infinite space.

But when this sexual repression was broken by the unconscious sexual instinct, Asenbach really realized the true meaning of art and beauty. At the end of the original script, Asenbach said: "We, the artists... By the way, that's what I'm going to say to you. We can't pursue beauty and refuse the coming of Eros... We men can use our The way to become a hero, to be a warrior who obeys the command of the battlefield, but in essence we are no different from women, because it is not ideals that motivate us, but the pursuit of hobbies and sex that drives us to success..." [5] That is to say, when Asenbach met Tacchio, he really released the passion of the id and stimulated the motivation of artistic creation. This change is reflected in the contrast of colors in the film. The scenes in which Asenbach appears in the whole film are dark colors. Whether it is his clothes or the furnishings and layout of his room, they are all elegant and simple. But when Tacchio first appeared, the use of color in the scene was gorgeous, from the vases in the hall to the jewelry worn by the ladies. And Tacchio's appearance made everything around him eclipsed, and Asenbach could only see the color of Tacchio alone (Figure 5). This also symbolizes that the appearance of Tacchio has added bright color to Asenbach's life. This young man like an ancient Greek sculpture is the only light in Asenbach's life. Asenbach's life has been injected with vitality and vitality since then, but it was short-lived. The vigor and vigor also became the fatal blow to kill Asenbach, which is another story.

Since first meeting Tacchio, Asenbach has been following and peeping at him, although Asenbach has never had any direct communication with Tacchio. Psychoanalytic theory holds that visual impulse is one of human sexual instincts, and it is the projection of the viewer's desire, thereby obtaining imaginative satisfaction. Therefore, what "seeing" itself confirms is not the satisfaction of desire, but the fantasy of desire. Aschenbach refers to the desire for gratification, the gaze at Tacchio, but Tacchio, the object of desire, always escapes from viewing. This also proves that this kind of looking is itself an imaginary look, and this look is influenced by the symbolic look that takes place in the field of the other from the beginning, which is why although Asenbach imagines that Tacchio His own gaze (Fig. 6)—imagines the actual gaze of the fixed other, but in reality, he is just "seeing himself", dominated and stared by an impossibility that has been lost in advance.

It is worth noting that the film naturally "objectifies" the world of the screen, and uses the "unique photoelectricity" in the dark room to focus on the audience's visual impulse, which also perfectly satisfies the audience's desire for voyeurism [6] . A second peep beyond the text. Metz proposes that film practice is possible only through the passions of perception, the desire to see (horizon-driven, voyeurism, spectatorism) that participates in the art of silent film alone, and the desire to hear, which is superimposed on the sound film. That is to say, the viewing of movies is also completely based on sex drive. "Sex drives are distinguished from other drives by being more dependent on absence, or at least in a more definite and unique way, from other drives, which even from the outset regard them as imaginary more than other drives. Lateral existential boundaries are marked." [7] That is, sexual drives are distinguished from purely organ instincts or needs (Lacan), or, according to Freud, from self-preservation instincts (which he later tended to attach to self-consciousness). "ego-driven" in love, a disposition he never could bring himself to truly pursue its conclusions). Sexual drives are fickle, adaptive (and fundamentally more perverse, Lacan says), and always insatiable. And the voyeur as a movie-goer earnestly maintains a gulf, an empty space between the object and the eye, the object and his body, pinning the object at a suitable distance that separates the voyeuristic object from the self , break, which forms a wonderful intertext and contrast with the peeping relationship between Asenbach and Tacchio. The split between the eye and the gaze, the split between the object and the self also indicates that viewing is doomed to be impossible, and in this split constitutes the tension of the protagonist's personality.

4. Self-Destruction: Misrecognition and Personality Wrestling

In the author's opinion, the core theme of "Soulbroken Venice" is actually the personality wrestling of the protagonist Asenbach. There are many disputes between Asenbach and his friend Alfred in the film - for example, for art, Gustav believes that "sensibility can never be sublimated into spirit", "art requires complete control over sensibility", while Alfred believes that "sensibility can never be sublimated to spirit" Germany believes that "talent is the spark of innate sin". In fact, we can think of these two characters as two characters specially set by Visconti-representing Asenbach's superego (Aschenbach) and id (Alfred), or using La In Kahn's theoretical terms - the misidentification of the self (Aschenbach) and his true self (Alfred).

Corresponding to the conscious and unconscious, Freud divided the personality into three structures - id, ego and superego. The id is the instinctive field of human beings, mainly composed of sexual instincts. It is the most primitive unconscious psychological structure and acts according to the "pleasure principle"; the ego represents rationality and common sense, and is the id regulated and modified by the intuitive system. Exercise restraint, take a circuitous approach to primitive impulses, and act according to the "principle of reality"; the superego is the idealized and modeled self, representing morality and conscience, and its task is to suppress instinctual desires, act according to the "principle of supreme goodness", and guide the ego Suppress the uncontrolled turbulence of the id, constantly stimulate the sense of indebtedness and guilt, and call on the self to return to moral norms. "Just as Asenbach did, initially rejecting the passionate ego, clinging to the rational ego, and finally reluctantly into the passionate embrace, this turn is inevitable." [8] Asenbach initially accepted the control of the superego completely. Acting, he worked hard for musical works, dedicating his time wholeheartedly to creation. He believed that all great things must be free from lust and moral corruption. After Asenbach arrived in Venice, his superego and id had a fierce competition. On the one hand, his id was deeply attracted by the beauty of Tacchio, longing to indulge in it forever and not want to wake up, but on the other hand, his id was deeply attracted by the beauty of Tacchio. , his superego realizes that Tacchio is the inducement for the appearance of the id, so the superego is struggling, constantly reminding the ego to act rationally, which makes Asenbach really have the idea of escape. It was only in the process of escaping that Asenbach's mistake in sending the wrong box gave him a reason to stay in Venice. In fact, in Freud's view, any mistake has its subconscious origin, which is due to semi-repression. Therefore, Asenbach's fault is actually his id. Asenbach's id began to slowly overwhelm the superego in struggles and debates and became his dominant personality. This is reflected in the lens language as a high and low contrast of viewpoints - in the many discussions between Asenbach and Alfred, Alfred is increasingly occupying the center of the lens, and shows a downward attitude, with On the contrary, Asenbach is always squeezed to the side of the lens, and it reflects the attitude of looking up, and the switching back and forth between the lens pitches reflects Asenbach’s (superego)’s inferior position in the dispute (Figure 7). ).

Using Lacan's theory [9] to analyze, the original ideal composer Asenbach is nothing but a misidentification of the hero's self in the mirror stage - the individual projects his own libido into the visible image on the mirror. He constructs the ideal image of the imagination, this image exists in the imaginary world, and then he converts his libidinal energy into the desire for the other of this ideal image, and then through the image of the other, that is, the idealization and objectification of the image. Achieving identity with others and constructing a unified self-integration. That is to say, Asenbach's misidentification of the self has created his ideal and successful composer identity. He believes that he is meticulous, rational, and moral, so he will develop himself along the foreshadowed ideal, but All this is but a misrecognition, a portent of doomed wounds and gaps. In movies, we can see many representations of mirror images. "When Asenbach put on a white tie and a tuxedo before dinner and looked at himself in the mirror, he looked clean and radiant - his hair was neat and his beard was trimmed. He looked well-mannered , well-informed and young. But we know the mirror is lying, and we 've seen him old on the boat—in tattered clothes, with a bushy beard, and eyes dazed and miserable." [10] , Every splendid hall is complemented by strong color blocks - vases, bouquets, lampshades, headgear, screens, etc. all show a variety of colors. On the contrary, every time Tacchio appears, he is wearing a bondage, and Visconti seems to use luxurious colors to contrast the innocence of the beautiful boy, which also implies the gap between the "rational" beauty in Asenbach's heart and the beauty of reality. Therefore, when the fatal trauma strikes, the rift between the self and the object widens, and his true self emerges in the tension of the inner conflict of the theme.

As mentioned above, Asenbach's narcissistic identification with the self in the mirror is also the "formal fixation" implemented by the self to the object, and the other and the self are mixed. That is to say, Tacchio is, on the one hand, the "placement" of Asenbach's libido, and, on the other hand, Asenbach's "mirror self" (Fig. 8). The energy and form by which the ego organizes its own emotions in what appears to be an erotic relationship must also be the energy and form that leads the subject to an aggressive relationship to himself and to others: a form that coagulates in the tension of the subject's inner conflict. In , this tension will eventually awaken his desire for the object of his desire for others, and the original collaboration quickly turns into an aggressive competition.

In the water city of Venice, Asenbach has undoubtedly fallen deeply in love with Tacchio. And Asenbach's ideal self does not allow such a thing to happen - falling in love with a same-sex, young Other, which is contrary to ethics. So Asenbach's ideal self began to fragment into some "fragmented body images". Therefore, Asenbach's image in the film becomes increasingly haggard and withered (Figure 9), which also implies the collapse of his ideal self. So, the aggressiveness of the subject begins to reveal—he gave up the chance to escape Venice.

5. Beyond Ontology: The Lost of Visconti and Thomas

Shapiro believes that efforts should be made to discover the special texture of his works in the personality of an artist, and then reconstruct the personality of an individual artist from his works. Therefore, we should also observe "Soulbroken Venice" from outside the film itself. Surprisingly, we can indeed find film director Visconti and novelist Thomas the same lost as the protagonist Asenbach [11] .

Asenbach's crisis also happened to novelist Thomas Mann. First of all, the motivation for the creation of the novel comes from a real travel of Thomas. In 1911 Thomas came to Venice and stayed for about a week. According to Thomas's wife, he "liked a beautiful Polish teenager in Venice to the point of death, and he was always watching him and his friends by the sea. He didn't go to Venice to follow him around, which is nothing. But the boy attracted him, and he often thought of the boy afterwards" [12] . Thomas’s thinking about crisis can also be seen from other works and documents of Thomas. In addition to discussing the existential crisis of artists, Thomas often makes the protagonist suffer from the torment caused by homosexuality [13] . Thomas himself admitted in his diary his fondness for boys before puberty, so the writer no doubt recognized this feature and incorporated it into his literary creation.

The same is true for Visconti, whose contradictions are no less than Thomas Mann, who has openly admitted his bisexual identity, and his lover Berg, like Tacchio in the movie, is a young and beautiful man, and Visconti himself is old. In addition, Visconti also publicly revealed his own Oedipus plot. The set for "Breakthrough Venice" took on the style of Visconti's childhood in the Lido, where the family used to vacation. The actor who played Tacchio's mother in the film also said in an interview that when Visconti communicated with her about the role, she felt that Visconti wanted her to be as close to her mother as possible. And "mother" is a very important role in Visconti's life, she is combined with the symbol of family to become Visconti's unconscious [14] . "Death in Venice" was filmed five years before Visconti's death. During this period, Visconti had entered old age and his thoughts had entered a period of introspection, so this film was not only about his lifelong pursuit of beauty The embodiment is also the end of his artistic career. In this film, he showed the contradiction of his personality wrestling, and also showed the eternal dilemma of the subject, "he can't get rid of the self-enclosed world with only memory, existentialism and artistic problems [15] ".

Freud's revelation of human irrationality is to make people fully aware of themselves, so as to sublimate their own instincts and realize the order of the rational world. "The sexual urge may abandon the previous purpose of partial gratification or reproductive gratification and adopt a new purpose--a new purpose which, although related in its occurrence to the first purpose, is no longer regarded as sexual , shall be called social in character [16] ”. This process is called sublimation. "Sublimation" is the mechanism of unconscious activity corresponding to "repression", which means that the unconscious instinctive energy can be transformed into a more lofty and socially valuable goal through advanced forms such as literature and art. Coincidentally, Thomas was indeed deeply influenced by Floyd, albeit very late. Thomas attempted to combine music, myth, and psychology with Freud's psychoanalysis, and he strongly agreed with Freud's analysis of the subconscious and myth, believing that he offered hope for a "wiser, freer human being" [17] . [18] That is to say, "Soulbroken Venice" is essentially the sublimation of the unconscious instinctive energy of Thomas and Visconti. They found an outlet for their impulses through literary and artistic creation, so their works themselves It shows the artist's main lost dilemma, which is also a perpetual dilemma - "Soulbreak Venice opens up a constantly generated text group and 'image field', a source from Thomas and Visconti but far from limited to In this field, its canonization process accompanies the turning of the times and the passing of grand things, it shows the dilemma of aesthetics, art, the times and life.”

6. Conclusion: the predicament of the doomed subject

Near the end of the film, Asenbach went to a barbershop, cut his hair and put on makeup (Fig. 10), hoping to regain his ideal self again. When he stared in the mirror again, he finally realized his self-misrecognition. , confirming the emptiness of the subject.

Freud believed that we must assume that there are two basic instincts in human beings, namely, the erotic instinct, which tries to maintain the unity of life or the body, and the destructive instinct, which tries to destroy life and return the body to an inanimate state. It is the "life instinct", which is called the "death instinct", and the aggression of the subject proposed by Lacan is a manifestation of the "death instinct". Lacan points out that aggression is a disposition that correlates with a mode of identification I call narcissism, which determines the formal structure of man's self, and of the realm of entities specific to his world . 19] . When Asenbach realized the fragmentation and incompleteness of the self, his identity structure was broken, and the aggression (death instinct) of the subject became more and more intense, so he walked to the beach, looked at Tacchio's figure, and walked towards death. This is also the inevitable outcome of Lacan's subject's dilemma - "this is an idealized voyeuristic-sadistic sexual relationship, a personality that can only achieve self-realization in suicide [20] ".

This subject dilemma is hinted at in many places throughout the film. For example, in the use of music, Mahler's Fifth Symphony is used as accompaniment in many scenes in the film - the opening scene of the film, the scene where Asenbach decides to leave Venice and meets Tacchio in the hotel, and the scene where Asenbach's daughter appears in the coffin in the interlude The scene, the scene where Asenbach follows the Tacchio family after putting on makeup, and the last scene where Asenbach watches Tacchio by the sea until he dies, etc. The first two chapters of Mahler's Fifth Symphony are pieced together from several pieces that Mahler composed in 1901, one of which, "I have become a stranger in this world," deeply embodies his presence in this world. A sense of alienation and alienation. "The Fifth Symphony is actually Mahler's psychic experience of walking into this real society that both disturbs and confuses him, the sum total of all the pain he suffered in real life, and the fact that he faced such a A spirit of struggle manifested by the reality of life and suffering, Mahler abstracted this connotation into the category of tragic contradictions of 'life and death'." [21] Visconti used in the film The scenes of Mahler's Fifth Symphony are all related to death, and they all show a trend toward death. This may be a kind of death destined under the predicament of the subject, and it is also the only way to reach reconciliation. It is worth noting that the names of "Aschenbach" and "Tacchio" actually contain metaphors for death, "Aschenbach" will be reminiscent of "ashes", and "Tacchi" The first syllable of "O (Tadzio)" is reminiscent of "tod (death in German)". [twenty two]

To sum up, the seeds of dissent that are planted during misrecognition will grow and develop with the nourishment of trauma, and the increasingly strong sexual instinct will break out of the body through repression. Therefore, Asenbach's personality wrestling points to the broken subject, to the predestination of the subject's predicament, and only death can achieve final reconciliation.

references

[1] [French] Metz, translated by Wang Zhimin. Imaginary Signifiers: Psychoanalysis and Film [M]. China Radio and Television Press, 2006.

[2] [Austria] Freud, translated by Gao Juefu. Introduction to Psychoanalysis [M]. Commercial Press, 1984.

[3] [French] Jacques Lacan, translated by Chu Xiaoquan. Anthology of Lacan [M]. Shanghai Sanlian Publishing House, 2001.

[4] Wu Qiong. Jacques Lacan: Reading Your Symptoms [M]. Renmin University Press, 2011.

[5] [Austria] Freud. Interpretation of Dreams [M]. Commercial Press, 1996.

[6] [Ao] Freud. Three Theories on Sexology [M]. Zhejiang Literature and Art Publishing House, 2015.

[7] Huang Liaoyu. Thomas Mann [M]. Sichuan People's Publishing House, 1999.

[8] Wang Ning. Literature and Psychoanalysis [M]. People's Literature Publishing House, 2001.

[9] Zhu Xiaolan. "Gaze" Theory Research [D]. Nanjing University, 2011.

[10] Jin Bo. Exploration on the Construction of Artists' Gender Identity: An Interpretation of "Death in Venice" [D]. Yunnan University, 2013.

[11] Liu Yang. Two Texts, Three Artists and One Theme: The Modern Dilemma of Art Creation from the Novel "Death in Venice" and the movie "Soul Break in Venice" [D]. Graduate School of Sichuan Academy of Social Sciences, 2009.

[12][Italian] Lu Visconti, translated by Zhao Xiuying. Soul Broken Venice (script) [J]. World Cinema, 1987.

[13] Cheng Runfeng, Li Anbin. Art·Death·Desire: Intertextual Interpretation of "Death in Venice" and "Soulbreak in Venice" [J]. Film Review, 2019.

[14][Italian] Jia Rondolino, translated by Yin Ping. About "Soulbroken Venice" [J]. World Cinema, 1987.

[15] Guan Rongzhen. Contradictions and Struggles - Interpretation of Human Nature in "Soulbroken Venice" [J]. Outside the Territory, 2006.

[16] Raymond Tarbox. "Death in Venice": The Aesthetic Object as Dream Guide. American Imago , Vol. 26, 1969.

[17] Carolyn Galerstein. Images of Decadence in Visconti's "Death in Venice". Literature/Film Quarterly , Vol. 13, 1985. pp. 29-34.

[18] Carrie Zlotnick-Woldenberg. An Object-Relational Interpretation of Thomas Mann's “Death in Venice”. American Journal of Psychotherapy , Vol. 51, 1997.

[19] Harry Slochower. Thomas Mann's "Death in Venice". American Imago , Vol. 26, 1969. pp. 99-122.

[1] [Ao] Freud, translated by Gao Juefu. Introduction to Psychoanalysis [M]. Commercial Press, 1984:269.

[2] Wang Ning. Literature and Psychoanalysis [M]. People's Literature Publishing House, 2001: 11-35.

[3] [Austria] Freud, translated by Gao Juefu. Introduction to Psychoanalysis [M]. Commercial Press, 1984: (forgot which page, too lazy to turn it)

[4] Raymond Tarbox. "Death in Venice": The Aesthetic Object as Dream Guide. American Imago , Vol. 26, 1969. pp. 123-144.

[5] [Italian] Lu Visconti, translated by Zhao Xiuying. Soul Broken Venice (screenplay) [J]. World Cinema, 1987: 111-159. But this part was not recorded in the film, the author thinks that maybe It was the director who thought that these words were too straightforward for the subject.

[6] Zhu Xiaolan. "Gaze" Theory Research [D]. Nanjing University, 2011.

[7] [French] Metz, translated by Wang Zhimin. The imaginary signifier: Psychoanalysis and film [M]. China Radio and Television Press, 2006: 55.

[8] Carrie Zlotnick-Woldenberg. An Object-Relational Interpretation of Thomas Mann's “Death in Venice”. American Journal of Psychotherapy , Vol. 51, 1997. pp. 542-551.

[9] Lacan divides people's spiritual structure into three types: "the Imaginary", "the Symbolic" and "the Real", which correspond to Freud to some extent. The three personality structures of superego, ego and id.

[10] Carolyn Galerstein. Images of Decadence in Visconti's "Death in Venice". Literature/Film Quarterly , Vol. 13, 1985. pp. 29-34.

[11] Because this article is mainly from the perspective of classic psychoanalysis, that is, focusing on the drive of sexual instinct, it will not conduct further personality analysis of Asenbach's archetype, the musician Mahler.

[12] Huang Liaoyu. Thomas Mann [M]. Sichuan People's Publishing House, 1999: 73.

[13] Liu Yang. Two Texts, Three Artists and One Theme: The Modern Dilemma of Art Creation from the Novel "Death in Venice" and the movie "Soul Break in Venice" [D]. Graduate School of Sichuan Academy of Social Sciences, 2009.

[14] Liu Yang. Two Texts, Three Artists and One Theme: The Modern Dilemma of Art Creation from the Novel "Death in Venice" and the movie "Soul Break in Venice" [D]. Graduate School of Sichuan Academy of Social Sciences, 2009.

[15] [Italian] Jia Rondolino, translated by Yin Ping. About "Soulbroken Venice" [J]. World Cinema, 1987: 160-165.

[16] [Austria] Freud, translated by Gao Juefu. Introduction to Psychoanalysis [M]. Commercial Press, 1984:278.

[17] Harry Slochower. Thomas Mann's "Death in Venice". American Imago , Vol. 26, 1969. pp. 99-122

[18] Cheng Runfeng, Li Anbin. Art·Death·Desire: Intertextual Interpretation of "Death in Venice" and "Soulbreak in Venice" [J]. Film Review, 2019: 77-79.

[19] Wu Qiong. Jacques Lacan: Reading Your Symptoms [M]. Renmin University Press, 2011: 132.

[20] [French] Jacques Lacan, translated by Chu Xiaoquan. Anthology of Lacan [M]. Shanghai Sanlian Publishing House, 2001:80.

[21] Jin Bo. Exploration on the Construction of Artists' Gender Identity: An Interpretation of "Death in Venice" [D]. Yunnan University, 2013: 31.

[22] Carrie Zlotnick-Woldenberg. An Object-Relational Interpretation of Thomas Mann's “Death in Venice”. American Journal of Psychotherapy , Vol. 51, 1997.pp.549.

View more about Death in Venice reviews