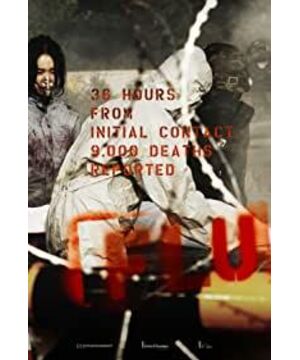

The movie "Influenza" shows a social landscape with obvious characteristics of the current era: once a disaster breaks out, the splendid and harmonious negatives will be torn to shreds immediately, and every citizen in the legal order will be surrounded by fear. It is the sovereign who declares that the community has entered an "exceptional state", and the patient's citizenship is taken away by the sovereign, and then he is imprisoned in a concentration camp to isolate the epidemic. Paradoxically, the patient's identity as the object of medical and epidemic prevention was replaced with a regional identity from the beginning, and the original purpose of medical assistance to eliminate patients was also transformed into a legal civil war aimed at eliminating the patient's body. The people of Bundang in the film have to face the reality that each of them has become a potential enemy of the entire community, and the identified patients will be in danger of being killed. Here, the sovereign issued a brutal killing order at the same time as drug research and development simply because he was worried about the spread of the epidemic.

When the epidemic was just announced, the movie focused on the supermarket. After learning about the epidemic, people panicked to buy goods. After the police issued an ultimatum that the supermarket was about to be blocked, people began to run for their lives. At the moment when the crisis comes, all the symbols and references of the consumer society have lost their former brilliance. The iron gates that are falling at a constant speed seem to be dividing the inside and outside of the legal order. If they do not escape from the supermarket, it means that they can no longer enter. into the legal order. Agamben uses "scared man" to refer to this group of outlaws whose lives can be placed at will by the sovereign, reduced to complete "bare life". In the concentration camps where the people of Bundang were imprisoned, no matter what a person's past social status was, his legal status was completely erased and replaced by a series of numbers. He/she would no longer be a living person, but It becomes an object that can be arbitrarily disposed of at any time.

This objectivity of the divine makes it impossible for them to evoke the sympathy of citizens within the legal order, and their suffering is reduced to a quantifiable indicator that the community can reject. What makes it shudder is that the prime minister in the film, in order to shoot the resisting Bundang people, said when persuading the more humanitarian president: "The intention to block Bundang has risen from 35% to 100%. Ninety-six." Obviously, the Korean people in the rest of the film almost ignored the lives of the people in the epidemic area, and all they hoped was that the disaster would not come to them. In a biopolitics with the safety management of life as its primary goal, the people are summoned to be a narcissistic subject - in order to defend this fragile and helpless self, any object that potentially threatens their "quiet" life must be Rejected, even mobilized people will be ruthlessly slaughtered. Žižek concludes: "Biopolitics is fundamentally a politics of fear, which focuses on defending against potential deception and harassment." It is this "politics of fear" that is exploited by decision makers who kill patients, and thus enforce Only then will they be able to complete this task, which is contrary to the spirit of humanity and the principles of democracy, with peace of mind.

Agamben argues: "The state of exception is neither external nor internal to the legal order, but the question of its definition is related to a threshold, or a zone of indifference, in which the inside and the outside are not mutually exclusive, but mingled with each other. ." The "exceptional state" deduced by "Influenza" precisely reflects this "mutual contamination" situation. On the one hand, the imperial order represented by the United States and the center-periphery system centered on Seoul are relying on violence to consolidate the original differential order in an exceptional state; but on the other hand, naked life in critical moments is a threat to them. The injustice suffered raises strong objections. The former uses extrajudicial means to strengthen the original legal order, and the latter challenges the previously unequal power structure in the process of fighting for legal power. This moment is not only a split law. The threshold between the inside and outside of the order is also the threshold that demarcates the old and new history of mankind. Benjamin pointed out:

Traditions of the oppressed tell us that the so-called "emergency" in which we live is not an exception but a norm. We must have a conception of history consistent with this observation. That way we will be clearly aware of it. Our task is to bring about a real state of emergency, thereby improving our position in the fight against fascism.

The "exceptional state" in the film is also what Benjamin called the "regularity". Creating exceptional people and excluding those who have no share has indisputably become the normality we face every day. In fact, modern society has reduced all of our lives to the point of nakedness, where everyone is a potential divine being at the behest of the sovereign. If we try to flip the narcissistic subject that has been made into it, we will find that it is not the people who are excluded from the order that really threatens us, but the "exceptional state" itself that can expel the other. The second half of the film tells of the rebellion of the Exceptional People, who are trying to bring about "a real state of emergency." In this "extreme" situation, the people of Bundang have come back together from their previous state of being separated by the capitalist order, demonstrating the courage and awareness to unite and forge alternative paths. Naked life is transformed into a new political subject at this moment, and they issue emergency orders over the sovereign to construct a new relationship of equality above the "threshold".

Yet instead of showing us the future of riots, the film uses "superheroes" and the conscientious ruling class as an intermediary to shut down a "true state of emergency" to restore an already precarious legal order, where once again conservative sensory structures become the new Barriers to the emergence of narrative. At the end of the film, the little girl who obtained the antibodies of the stowaways in Southeast Asia finally survived, and she became the hope of treating all patients. At this time, a South Korea still in the imperial order and playing the role of a "sub-empire" no longer regards the stowaways as an abstract external incarnation that needs to be destroyed, but affirms the significance of his salvation for South Korea, but when the rescue is completed After that, he will also be completely abandoned, and hope will inevitably be projected only on the "vigorous" bourgeois children within that community.

View more about Flu reviews