Nietzsche - The Genealogy of Morals

4

In the longest period of human history, there was no punishment at all, because people held the perpetrators accountable for their actions, rather than only punishing criminals as a premise - more like parents punishing their children today, Annoyed at the troublemaker for having suffered a loss, - however, this anger is limited and mitigated by the idea that any loss will be compensated, and that the loss can really be offset by compensation, even by the troublemaker pain can also be. The old idea that loss is equal to pain is deeply ingrained and may not be removed today. How did it gain such power? I have already guessed: it arises from the contractual relationship between creditor and debtor, which is as old as the existence of "legal subjects" (23), and which can be reduced back to the basic forms of buying and selling, exchange, trade and communication go up.

(23) [Pütz Edition Note] "Legal subject": All individuals who can enjoy rights and perform obligations under the relevant legal regulations. Nietzsche may have put quotation marks around the word to emphasize that they are, in fact, objects of law.

5 However, as one might expect from previous explanations, the assumptions and interpretations of these contractual relationships raise questions and resistances against the ancients who created or endorsed them. It is here that the act of promise takes place; it is here that [299] the question of keeping the promiser remembered; there is every reason to doubt with negative emotions, and it is here that one will find cruelty, cruelty, and torture. In order to make people believe in his promise to repay the debt, in order to ensure the sincerity and sanctity of his promise, and in order to make his conscience remember that repayment is his duty and responsibility, if he cannot repay the debt, he will take possession of his usual "possession" according to the contract. ” and at his disposal to the creditor, for example, his body, his wife, his liberty, and his life (or under certain religious preconditions, the debtor may even mortgage him "Happiness in Elysium," the salvation of his soul, and even his peace in the tomb: such was the case in Egypt (24), where the creditor did not even let the body of the debtor rest in the tomb - and the Egyptians were focus on this tranquility) (25). In particular, it is important to note that the creditor can insult and torture the body of the debtor at will, for example, by cutting flesh from the debtor roughly equal to the amount of the debt: - On this basis, there have been formerly claims about human limbs and body parts all over the world. The estimates of the various parts, these estimates are precise and detailed, and some parts are even horribly detailed, and their existence is legitimate. (26) The Roman Law of the Twelve Tables (27) states that the creditor in this case is the same regardless of how much or less, "si plus minusve secuerunt, ne fraude esto" (28), which I think is It is already an advance, proving that the concept of law has become freer, more generous, more Romanized. Now, let's figure out the logic of this whole form of compensation: the logic is very peculiar. The realization of equal repayment is not to directly compensate the loss through property (not to compensate with money, real estate, or other property), but to entitle the creditor to obtain some kind of pleasure as repayment and compensation, - this kind of pleasure is the creditor The unbridled exercise of power over the disempowered [300] is the lust that is "de faire le mal pour le plaisir de le

(24) [Pütz edition note] Egypt: Nietzsche's suggestion of tranquility in Egyptian tombs refers both to the sanctity of the tomb and the expense of sacrificing the dead, and to the robbery of tombs that was once officially organized. According to the ancient Greek historian Herodotus (490-422 BC), Egyptians at the time (around 2480 BC) could borrow money using their father's mummy as collateral (see Herodotus "Aboriginal History" Volume II Section 136).

(25) [Annotation] See J. Kohler, Law as a Cultural Phenomenon, An Introduction to Comparative Law (Das Recht als Kulturerscheinung, Einleitung in die Vergleichende Rechtswissenschaft) Würzburg, 1885, pp. 18-19.

(26) [Annotation] See Albert Hermann Post's book "An Outline of a Universal Jurisprudence Based on Comparative Ethnography", Exhibit 1, pp. 334-336.

(27) [Pütz Edition Note] The Law of the Twelve Tables: This is a decree issued by the Roman Senate in 450 BC with the support of the people. These decrees, in place of the Romans' traditional customary law, were engraved on 12 bronze plates erected on the market square. Although it has been expanded and reinterpreted many times during this period, its basic content has been preserved until the end of the Roman Empire.

(28) [Note to the Pütz version] “si plus minusve secuerunt, se fraude esto” ([Translation] the last sentence was originally written as ne fraude esto in the KSA version, and is now corrected according to the Pütz version): “Whether they cut more or less, they are all should not be counted as illegal" (se = sine: no, not meaning). This clause is taken from the sixth section of the third plate of the Twelve Tables.

(29) [KSA edition note] "de faire le mal pour le plaisir de le faire": French, meaning "do evil for the pleasure of doing evil". See Lettres à une inconnue, Prosper Mérimée Jenny Dacquin (1811-1895), a collection of correspondence for nearly forty years, published by the latter after Mérimée's death), Paris, 1874, I, 8; Nietzsche in "Humanity, Too This quote is also quoted in Quote 50 in The Humanity.

(30) [Annotation] One with authority above: From the Book of Romans in the New Testament, see the related notes on verse 14 of the first chapter of this book.

8

Perhaps in our language, the word "man" (manas (56)) expresses such a sense of self: man calls himself a being that measures value, evaluates and evaluates, and calls himself "innately capable of estimating value". animal". Buying and selling, with their psychological properties, are older than even any primitive form of social organization and social group: among the most primitive forms of The budding consciousness of debts, rights, obligations, and compensation was first transferred to the most extensive and primitive public groups (that is, in the relationship with other similar public groups), along with the comparison, The habit of measuring and calculating power. And people's eyes have also been adjusted to this angle: the ancient human thought, although clumsy, would stubbornly continue in the same direction, and with the continuity unique to this thought, people immediately concluded That great universal conclusion: "Everything has its price; and everything can be repaid" - this is the most ancient and naive moral law that belongs to justice, all "good" and "fair" ” (58), “goodwill” and the beginning of “objectivity”. This rudimentary justice is the goodwill that prevails among those who are roughly equal in strength, the mutual tolerance between them, the "understanding" reached by some kind of coordination--and[307] when it concerns the weaker , it will force the weak to reach a certain coordination within.

(56) [Pütz Edition Note] manas: Sanskrit, meaning "consciousness", from the Hindu classic "Veda". ([Translation] The parentheses in the text were added by Nietzsche himself. He first used the German word Mensch [person], and then added the Sanskrit manas in the following parentheses, which should be to show the etymology of the two. (57) [Pütz Edition Note] The most primitive form of personal legal rights: contract legal rights (promise legal rights) and goods legal rights (income legal rights and property legal rights) together constitute an individual’s private legal rights, The opposite is the right of public law, and the right of penal law is an important part of the right of public law. And Nietzsche in "The Genealogy of Morals" deduces the law of punishment from the right of individual law, and also subsumes it into the right of individual law.

(58) [Pütz edition note] Fairness (Billigkeit): Unlike a strictly indictable claim to justice, "fairness" involves giving a Compensation for concessions made (cf. Kant, The Metaphysics of Morality, 1797, pp. 38 et seq.).

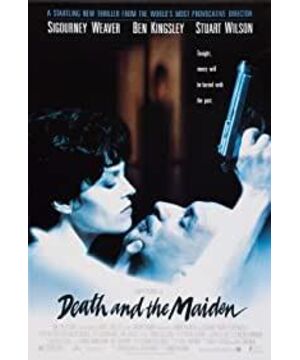

View more about Death and the Maiden reviews