This text is a translation of Lolita: The Book of Images (Praise Books, New York, 1998) and is the introduction to the book by Stephen Schiff. In the article, Stephen introduces himself as the script writer of the 1997 version of "Lolita" (aka "A Tree of Pears and Begonias"), as well as the challenges of the film's screening and distribution due to its sensitive content. This article is an excerpt from Stephen's thoughts on Nabokov's original book and his reflections on the adaptation process. Introduction: The screenwriter talks about "Lolita" (the subtitle is proposed by the editor)

*The article was first published in the 2009 01 issue of "World Film" magazine, the translator is May 7. In order to obtain reprint authorization, please contact the original author for reprint. Text | Stephen Schiff

Translation | Five Seven

The full text is 7563 words, and it takes about 12 minutes to read.

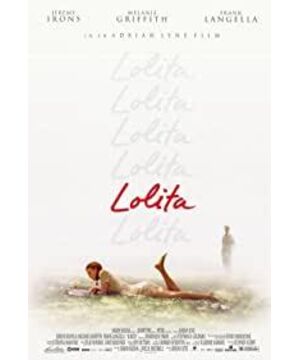

This is the story of a film — albeit only part of it — and whether you like it or not, there can’t be more to say about it. The $58 million new film "Lolita," written by me and directed by Adrian Lane, has become the most controversial work of all time. To this day, it's also the most famous unreleased film of all time -- the most talked about, the most written about, and the worst reputation for people who haven't seen it at all. By August 1998, when it made its debut to the American public on the Showtime Channel, it still had a very dubious reputation for premiering the most expensive film on television. Once hailed as the most refined film ever made by a very successful director, Lolita is a faithful, moving, and finely crafted visual representation of a complex and difficult literary masterpiece. It has also been denounced as murky and meaningless, or even worse, endangering society, instigating pedophilia, and simply a model that tramples on social morality.

My first draft of the script was also similar to what happened to Lolita. So why should I, and everyone else who has had the idea of adapting it, give it a try? In my pen-and-ink career, my primary role was that of a newspaperman - I thought, a cultural critic, self-righteously talking about books, theater, ballet, and above all, about movies, in the circle of script writers The often-heard stories of dishonesty or betrayal indicate that the temptation to dabble in the business of scripting is not so difficult to overcome. Also, I don't think it can be written. And, more than that, it doesn't mean that you can write something, and that you know movies, means you can write movie scripts. So, no matter how much my cerebral cortex was stimulated by the urge to write a book that lurked there, I was still focused on my newspaper business.

Of all the various people who push me from time to time to write a movie script, there is only one I really trust - producer and director Lily Finney Zinack. In 1990, when literary agent Owen Lazar was about to sell his rights to adapt the literary legacy of Vladimir Nabokov, Lily told me she thought I should adapt Lolita as The perfect choice for a movie script.

"Lolita" is one of the most beautiful, poignant, most interesting, most ingeniously designed, most brilliantly written, and most acutely psychologically portrayed works in English literature. In my opinion, it is the greatest novel of the postwar era. So the opportunity to have an artistically equivalent response to such a masterpiece—if it was an opportunity at all—was hard to resist.

I really moved my pen, but I had to add a quick one, which I did very stupidly: I wrote about 40 pages, but it was basically all dialogue, and there was no "stage direction". I don't have enough patience for the idea of describing what people have done. On the contrary, I am very attentive to what they have said; wherever the characters have actions in addition to their words, I write, "Stage Instructions KT" (KT means "future to be done" in US news style) and I know now that this method betrays how ignorant I am about script writing, because the screenplay is really a part of what you think of the film in your head. A prospect, to seize it in its fleeting moment; the difference between dialogue and stage direction is not so well-defined.

But, still somewhat sad, Lily called me a few weeks later and said, rather presciently, "Forget it. Any adaptation of Lolita in this political climate It's all going to be too controversial. It's impossible to start filming."

In the fall of 1994, I got a call from Lily's husband, Richard Zinack, who is now a producer on Adrian Lane's Lolita project. "Lily said you wrote part of it years ago," Dick said. "Send it here." I sent it over. Days, not weeks, passed. Dick Zinack's call came again.

"Stephen, we like your manuscript," he said.

"My manuscript is absurd," I said.

"Oh, I think it still says something," he said.

"Now, here's what you have to do: Find the cheapest way to get to the airport. Get the cheapest flight from New York to Los Angeles. Get the cheapest room in town. Then, come with me and Adrian Lane rendezvous." Finally, he did not forget to add the most crucial sentence: "Ah, these expenses may not be reimbursed."

I went. The meeting took place at Zinack's office in Beverly Hills. The first thing he and Adrian wanted to know was whether I would like to set the film in the present. (I didn't know it at the time, that's what Dearden's draft did.) The answer they got was "no."

A Lolita living in America today should have been warned by Humberts of the world as early as 3 years old; her teacher would talk to her about pedophilia; her mother would always be careful everywhere. . In addition, if I really want to leave this story of Nabokov to the present, I am afraid that I will lose a lot of the original title, because this novel is not all about an adult man and his 12-year-old. A love affair between stepdaughters also touches on how the dawn of dawn shone on European sentiments in postwar America. It's about how a refined, elegant old world plunged headlong into the arms of a crude, beautiful, childish, indisputably strong, young America that emerged only after World War II. And indulge in the process. Nabokov sets his novel in 1947, a very unique moment in American cultural history—before the rambunctious, hilarious 1950s was on the horizon; Before the colorful consumer culture that was compatible with it prevailed. It's an America that has never been fully explored in film, and Nabokov has woven it all neatly between the lines of his novel.

A few weeks later, we met again in New York, in Adrian's room at the St. Regis Hotel. It was more of a rambling, aimless chat, which was also enjoyable. But Adrian couldn't sit still and went to another room to call. He's inviting David Mamet to write the script for Lolita. To put it bluntly, I have a gut feeling that he might be able to write amazingly good stuff, but he's unlikely to write a script that can be shot.

So I just write it down, even if I'm trying my luck, at a fast marching speed. Sitting in front of a computer typing on a keyboard has never felt so exciting. It's just that this time, it's not like the first test in 1990, when a whole movie pops up in my head. In front of you, you can see the scenes, not just the words; the characters have character, not just dialogue. Things started to go smoothly. And just like that, three weeks passed. I'm waiting. Zinack called and told me that Mamet's script didn't pass. I said to him, I have something here for him to see. I sent the manuscript over. In an instant, a Hollywood satire came true for me. But what did I write? Let's start from the beginning, we all know very well that this film is not a "remake" of Stanley Kubrick's 1962 version (the script for that time is different because Kubrick wrote it himself. Glory, even though the stuff in his script has largely failed to make it to the screen).

In fact, the vast majority of us on the team see the Kubrick version as a template for "can't do that". (Nabokov’s own famous analogy is that watching Kubrick’s film is like taking a quick glance at the countryside—like a patient sitting in the back of a speeding ambulance.) And I The impression of this version is much better, but I watched it almost 14 years ago, and I consciously did not allow myself to watch it again. My only source of information is the original novel itself. As much as I've always loved this novel, I'm also very aware that a lot of it has to be discarded—even if it's my true love.

Not long ago, my friend Jason Epstein, the well-known editor of Random House (who pushed Nabokov's novel to be published in the United States), publicly expressed disdain for our adaptation ( Of course, without seeing the manuscript), I think that the beauty of "Lolita" lies in the style, that is to say, making a movie can only grasp the fur of some plots of the original book, Such a project is almost worthless. This view does not represent Jason's usual level, because he is usually wise and insightful, but he is stupid on this unique issue. First of all, Lolita would not be a masterpiece if it had only stylistic ingenuity and ostentation. Nabokov's stylistic success is not just the book's style and tone, but its substance. (Extremely speaking, when it comes to "Lolita", the style is the essence.) As long as the interpretation of the original work in the form of a movie is faithful, it is impossible to reflect the infiltration of the characters, dialogue, image and plot itself. stylistic style. In addition, Nabokov is not only a great stylistic expert, he is also a master of plot - the story structure of "Lolita" is a miracle in itself, and the skill of splicing can be called magic. This is all the more so given that the entire event is slowly leaking through the consciousness of one of the most unique and wildest characters in literary history, Humbert Humbert.

Humbert was endowed with all the nobility, but he was mired in the ugliness he had committed. Part of his tragedy—and to a large extent his comedy—is that its immense ingenuity has always been defeated by his obsessions. He can't always break the fascination, and he can't see who Lolita really is, and he can't see that she is just a very ordinary little girl, more attractive than other little girls, perhaps more sexually aware than Most little girls are more precocious, but at the end of the day she's still a child. Humbert's inner world is entirely subjective, a world of language and fantasy. But in the film I have to externalize it. Nabokov's prose can be submerged and animated on paper, but it is difficult to express in film; and if these things come out of the mouth of a flesh-and-blood actor, they will It seems pretentious, fussy, silly and stupid. The best way to do it is to present them in a knowing way—and, even then, do it with extra caution.

As for the dialogue itself - yes, in the original novel, the comprehension is very subtle. Nabokov likes to hint at what he is about to say with just a sentence or two, for example, "I'm going to give a big talk about my Arctic adventure." As a screenwriter, you have to put together this so-called "big story" out of thin air. ' and 'special' telling - of course, the result is likely not as 'big', as 'special' as Humbert ostensibly claims. When those dialogues flowed out of Nabokov's pen, the vernacular of juveniles around 1947, whose voices were high and low, were not necessarily particularly idiosyncratic in terms of what Nabokov heard. As a result, a considerable portion of the dialogue that appeared in my script was not in the original—and even to such an extent that some critics thought I was copying the original. Another point is that since Nabokov's Humbert lived in an extremely subjective world, and Lolita herself existed in fragments in his imagination, such an incomplete image can only live in the volume. superior. So, I had to make another her, using my own and the young Meng Lang I know to cut and stitch.

Adrian has experience raising a daughter herself, and her memory is full of the little things in her life—food, toys, clothes, that sort of thing. When I think about the only things I have a strong, unbreakable relationship with little American girls, I tend to fall on food; so, most of the things that come to mind are Oreos, magic bread, bananas, candy balls—these Can't be found in Nabokov's book (sadly, a lot of it was cut from the finished film).

So, where did this little girl come from? This is a problem. I also had to create a relationship between Lolita and Humbert, a relationship that is told in the book entirely by Humbert's own unreliable narration, and we see only surprise in our eyes. Hong glanced. For example, there are many moments like this in Humbert and Lolita's long trip across the country, where they are actually a couple -- a strange couple (according to Adrian ), but not a couple in the general sense. Nabokov leaves a lot of room for the reader to imagine, but I don't think I can rely on it, some of the most vivid scenes in the film are when the two are on the road, testing each other, refuting each other, and, Yes, and love each other too. (The claim that our version is far more explicit in terms of sexual performance than the previous version doesn't seem to make sense without a couple of sentences, yes, in Kubrick's version, there's really nothing more than a kiss on the cheek An erotic move. But, in my opinion, sex just plays exactly the same role in our on-screen interpretation as it does in the original, with no more, no less emphasis.)

Suffice it to say, from the beginning I basically agreed with Adrian's take on Humbert: we have to sympathize with, and, yes, love him, even if his behavior makes us sick. In the end, that's exactly what Nabokov did - or, arguably, the vast majority of the greatest works of literature have always been doing the same thing: by leading us into a person's soul, and through our Likes, let us know him more deeply, not only his brightest side, but also the darkest corners of his personality.

There are a few ways I cut in. First, Humbert has to be funny, charming, sarcastic, and even a little naughty. I have to get him to wink at the audience from time to time, and I do it in a number of ways: with sarcastic puns, with suggestive voiceovers, with awkward and awkward moves (as in Rita examines her belly in the mirror during one of the fights). There is another important step in the process of humanizing Humbert: as Nabokov did. Both Adrian and I wanted to connect Humbert's obsession with Lolita to the fascination with which Humbert started it all when he was 13, Annabelle, his lost love. So I had Humbert tell us in voiceover, "Her death froze something in me. The child I loved is gone, but I'm still after her—long gone in my own childhood. Later..." This connection is firmly established through the corresponding images.

As the script took shape, there was always one word that bothered me, no matter when it came up in a discussion—every time I had a “storymeeting.” I call it "Character Arc". A movie character can't stay dead for the two hours of screen time allotted to him; he has to change, he has to develop -- in the extreme, he has to learn something. I hate this law, but it is one of the most important laws of narrative. Without an arc of growth, there is a great danger of being just a sitcom character. (In fact, one of the things that differentiates sitcoms from films is that sitcom characters have a constant quality that drives them to do their own thing, week after week. Not in Seinfeld Which one has this arc of character change.) Achilles in the Iliad has an arc. Othello, Macbeth, Hamlet, King Lear, they all have arcs; Michael Corleone has arcs; Bonnie has it, Clyde has it.

Likewise, Humbert needs to have such an arc. Can't resort to sentimental lines, and can't go beyond the audience's comprehension, then I have to show how he struggled from the pain, what an emotionally poor family he was who needed to learn how to love - what he felt about himself. After all, what Lolita did was deeply regretful. The arc begins with his shady and self-absorbed psyche while living in Charlotte Haze's house, and ends with three key moments, the first two of which I created for the film: Humbert Asks Lori Ta, can she forgive what he did to her (and he knew, she never forgave him); he told Quilty that he had to be killed because he stole Lolita , while Quilty deceives Humbert with his remorse; finally, the film's final voice-over (a remix from the original book), his love for Lolita, and the symbolic deprivation of Lolita by him The childhood handed back to her is confirmed in it.

Another point, "Lolita" is not just a book, it is a mystery. No one can read it through once; that means reading it at least twice, and until it does, all the tricks and motives contained in the puzzle—especially the part that involves Quilty—are self-evident. will be clear. As for me, I had to write a film that the audience could fully understand. This is both subtle and tricky. Stanley Kubrick sidesteps this dilemma entirely by having Peter Sellers essentially improvise throughout the film (I often wonder if his film should be called Quilty) . Kubrick begins with Quilty being killed, so that the audience is clear from the start who is the enemy in the shadows. While I want to deal with Nabokov a little more, I hope that Quilty's mysterious presence in the script has at least roughly the same effect as the novel's surprising encroachment on Humbert's life. Effect.

In the Los Angeles area, we had three test screenings, each of which was well received. We continue to patch and delete. With some trepidation, we show the film to Dimitri Nabokov, the only son of Vladimir Nabokov, the meticulous caregiver and executor of his father's estate. He praised it as "wonderful," before issuing a statement: "The new Lolita is a film that needs to be tasted and well-made. It is by no means a shockingly blunt bargain, like Others feared or expected that Lolita had reached the depths of a poetic film that was closer to the original novel than Stanley Kubrick's other work of the same name... Lane "Lolita"...and Schiff's script, which tends to let the audience's imagination run free, just as Nabokov's words are for the reader...this latest "Lolita" Rita's is fantastic."

In March 1997, two years after the script was finished, it was time for a preview to potential distributors, studios. What happened next was very strange. One by one, the studios watched the films. A lot of heads came here to congratulate Adrian, and further down, one was counted as one, and they never mentioned the issue of the release. "It's a really good movie," an unnamed executive-level figure said in the Washington Post. "But it's not what we want. It's still a hot potato. It's tasteful, but it's still uncomfortable." When it comes to uncomfortable art, there are those of us who agree—in fact, we I believe that art is not art if it does not make people uncomfortable. The aragonite produced by the pearls seems to have little comedic darkness in the heart, and the dissonant harmony of the counterpoint voices - laughter and scolding are all articles. But, of course, the art here is not the problem.

Finally, the film premiered in September 1997, at the Sebastian Film Festival in Spain. Mixed reputation. But the whole situation has not changed, and the film is still strictly prohibited from being shown in the United States. Fear prevailed. But what are you afraid of? It boils down to the simplest sentence, and the argument against the release of "Lolita" is this: A person walks into a movie theater and sees a film that is meaningful, funny, tragic, and complicated. A film that has been repeatedly emphasized or tried to make it memorable, just a film that tells the life of a pedophile from beginning to end, and this man will slap his head and realize, "Hey! Pedophile Great idea! Why didn't I think to try this!" Ridiculous, but that's what happened. Would it be useful to point out that the human sexual psyche does not function in this way? Isn't it clear that a pedophile can be easily aroused by anything we see as irrelevant - The Wizard of Oz, Lacey the Dog, need to list? Wouldn't someone who wasn't a pedophile suffer from it just because he watched "Lolita"? As long as the inner darkness is properly hidden, nothing will happen, as many people in our culture have always believed. Confidential. There is no violence without violence in the movies. If the cultural environment does not give criminals "suggestions", there will be no sexual crimes. Guns don't kill people, and it's not the same as killing people on TV. and so on.

The fate of the movie "Lolita" and the strange image of the novel "Lolita". In 1954 Nabokov's magnum opus could not find a publisher in the United States; in 1955 it was printed by Olympia Press in Paris, a bookstore known for its erotic literature. It wasn't until Graham Greene hailed "Lolita" as one of the three best books of 1956 when it was barely noticed that the impression of the publishing house was completely changed. France immediately banned it; British columnist John Gordon called it "the most obscene book I've ever read", but that changed when it was published in the United States in 1958. It became an instant bestseller.

The movie "Lolita" still enjoyed a somewhat strange fate. In the spring of 1998, the most bizarre reversal took place in surprising ways, when the high-quality cable network Show Moment bought American rights to the film; in August 1998, it was broadcast to people of all ages across the United States. "Lolita"; later, perhaps a wave of pedophilia will lead to a series of theatrical releases. Perhaps you, dear readers, will also study my script and slowly discover that you too have developed a new, uncontrolled, perverted craving. But I don't think so.

I hope you will at least laugh from time to time, once a while, and perhaps be moved.

*The article was first published in the 2009 01 issue of "World Film" magazine, the translator is May 7.

Thanks to the World Film Editors for this article

View more about Lolita reviews