The "the funny man" in other people's mouths is actually both sad and unaware of his own comicality. Chaplin achieves self-referentiality and self-deprecating dissolution of the meaning of comedian identity. Comedy is already an existence that is identical with the comedian's personal life, so even their tragedies are regarded as comedy pastimes. They are both the kings of the stage and the puppets of the audience.

The little tramp is watching a circus demonstration, and the multiple identities on and off the stage can be compared to Sherlock Holmes II—this can be seen as his and Keaton’s answers to the same issue from different perspectives: film or stage as a window, Keaton used it to face fantasy, dreams and the future, Chaplin used it to face reality, the heart and the present. How does the little tramp (also Chaplin's body), as an actor, examine himself as the other (audience), and at the same time, what attitude does Chaplin, who is the director, look at this kind of examination behind the camera? Echoing the previous metaphor of the labyrinth of mirrors, there is the trembling of being lost in multiple identities.

It may be because the filming era was in the transition period from silent films to sound films, and the film was rarely full of self-doubt. The shadow of the big studios gradually shrouded every freelance creator, and Chaplin's existing fame and fortune was a shackle in itself, so the fear of exhaustion and the reality of being famous was especially strong. Reflected in the film is the unusual use of dangerous stunts such as lion cages and high-altitude wire ropes. "swing high to the sky and don't have a look at the ground" sung at the beginning is a solution to this, but Chaplin is obviously not as obsessed with his own superiority and crisis as the little tramp. It is the fundamental difference between ontology and persona. Presumably he also envied the little tramp.

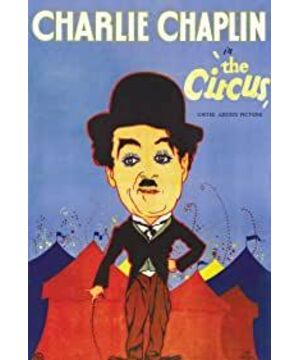

View more about The Circus reviews