De Sica, the allegorical poet of "Three Drawers of Buns"

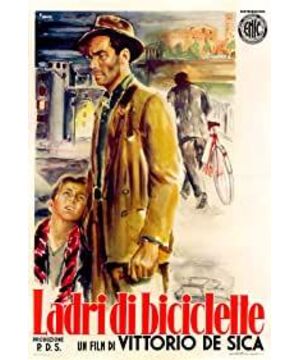

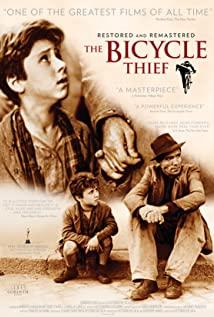

Except for a few Western commentators occupying high positions in historical observation, probably few have a position to say that De Sica is underestimated. After all, he is one of the core figures of Italian neo-realism, and neo-realism is a mountain that all film-loving and film-learning people cannot get around. The flag is shouting. But De Sica is not without "neglect", and people's understanding of his life achievements can easily stop at the trilogy "The Shoe Shine Boy" and "The Bicycle Thief" as a "classical" model of neorealism How "Wind Candle and Tears" matches the principles of neorealism. Real scenes, non-professional actors, daily life and social care, these few phrases label what neorealism is, but they also cover up neorealism under the wooden frame, making people feel that stereotyped records are mediocre repetitions that it cannot get rid of. one side.

The film masters Visconti and Rossellini, who are the same generation and representatives as De Sica, have demonstrated their insight and transcendence of neorealism with their elite posture and opening and closing approach respectively. The Milan noble Visconti believed in Marx and was the initiator of the "disloyalty" of neorealism. He studied with the famous French director Jean Renoir and opened the discussion on neorealism with "Down", but he did not stick to it. Relevant creeds sometimes change in form around their chosen themes. Rossellini has a more formal and innovative spirit. He has been diligent in studying the possibility of free creation since he joined the film in the 1930s. At the end of the war, he used a camera to record the life of the Italian people, thus giving birth to "Rome, Undefended City". This film Considered the official starting point of Neorealism, he then looked beyond social life, completing a series of works that are regarded as the beginning of modern cinema. That is "Love on the Edge of a Volcano", "Visit to Italy" and so on that Beijing fans saw last week.

If Visconti clarified the position of opinion represented by the term, and Rossellini created the conceptual basis for its germination, then De Sica expressed all the emotional concerns that neorealism might contain. It is evident in his insistence on people, human nature and humanism, as well as the rich emotions expressed through images and images. But this does not constitute any advantage in speech. How can the word "emotion" be advertised? Everyone has emotions, can emotions be outstanding and different from ordinary people? De Sica did not choose to be different from ordinary people. He chose ordinary people's emotions. Under his mirror, ordinary people suffer from daily hardships, daily poverty, illness, betrayal, and harsh treatment. He interprets but does not criticize, sympathizes but seldom supports, he magnifies truthful psychology and emotion to the greatest extent, almost beyond reality, so he gets the evaluation of "sentimental" - this is what we heard when we were students Yes - De Sica is too sentimental, too sentimental. De Sica fans and researchers have found an explanation for this: Modern audiences sometimes distrust presentations that bring us to tears, even though "De Sica sentimentality is some kind of easier sentimental hedge" .

Whether in the historical context of Neorealism from the postwar to the early 1950s, after the turn to Italian-style comedy, or in other more individual works, the realities of people as a collective are the basis of Desica's work. Taking the beginning of the "Trilogy" as an example, "Shoe Shine Boy" has the opening subtitles in the background of an empty mirror of the prison that hints at the characters' later fates. Next to the government officials who are about to be assigned positions, "Tears of the Wind and Candle" allows the audience to see the parade of retired workers demanding better pay. Rather than staring at a single person, his camera prefers to face the lives of a group of people. Konogonda, a new Korean-American director, once peeked into the leopard, took De Sica's brushstrokes as the standard of neorealism. In 1952, De Sica collaborated with Hollywood producer Selznick on a derailed melodrama "Terminal" starring a Hollywood star. Kang Gongda in his short film What is Neorealism? , compares the respective cut versions of De Sica and Selznick. The biggest difference between them is that Selznick cut out all the passages where De Sica doesn't follow the protagonist's actions and lingers on the extras. Selznick's logic is studio, Hollywood, and De Sica's choice is neorealism.

Reality is sometimes seen as a constraint on neorealism—some critics argue that this confines the film's scope to one's outer life while ignoring the inner world—but these luminous films bridge the gap between poetic realism, Before psychorealism, their presentation of post-war Roman reality was completely different from the later independent films that seemed to be low-budget, live-action, non-professional actors, and the way regular documentaries or so-called documentary-style social films reproduced reality. . De Sica once emphasized this point in an interview: "Neorealism is the exact opposite of the realistic style, it is not reality, it is not naturalism, it is not realism, it is reality filtered out by poetry, it is pure and bright. Reality." The poetry that Zavatini, co-writer and promoter of Neorealism put into his writing, shines brightly in his shots. All audio-visual elements have carefully designed metaphorical colors, and each frame emphasizes its dual psychological effects on the characters and the audience. As the camera moves away from the characters, we can hear de Sica's cues: Look, you've guessed how they're going to be treated, and you've seen hope and hope. Putting aside our prior understanding of the meaning of the textbook "The Bicycle Thief", we re-examined this work. What it surprised us was the dream-like fluidity, a man who has lost his basis of existence and is about to face despair. People of tomorrow will roam the streets and underground of Rome, looking for the possibility of continuing their life, looking for clues to old fantasies, and seeing all kinds of people living, performing, resisting and enjoying themselves in this city. In the false alarm of losing his son, the father experienced a moment of relative lightness and satisfaction, but was quickly overwhelmed by the cruelty of reality. There were bicycles and bicycle parts everywhere, and he ended up being driven mad by this constant repetition, overprinting, and vision. In the last shot, he held his son's hand and walked into the crowd, leaving the audience with a full picture of the back of his head, extremely depressed and desperate, and the suffering of one person has become the suffering of everyone.

Interestingly enough, despite Zevaratny's famous quote about "the function of the film is not an allegory" or "a hungry man, a humiliated man can only be presented by his full name, not allegorically". The identification of poetry and fables is indeed an important way to watch the films of De Sica and Zavatini, which is the spiritual content they cultivated and extended from reality. The influence of Neorealism is far-reaching and extensive, setting off a new wave in France, and the waves that follow one after another. Its radiation products can be found in France, Portugal, Asia, and America. Inside Italian films, the clues of its inheritance may be clearer. For example, last year's Palme d'Or winner for best screenplay "Lazzaro the Happy" showed references to De Sica's films. The well-loved treatment at the end of the film—the lone wolf who brought Lazaro to life, came from the mountains and took his soul away—resonates with De Sika and Chaifa in "Shoe Shine Boy" The poetic moment that Tiny co-created, the steed that had entrusted the friendship and hope of the two brothers, stepped away in the dark night of death. The story of Lazzaro, the ignorant saint of the industrial age, can basically be regarded as a variation of De Sica's neglected masterpiece "Miracle of Milan". Lazaro and Toto, who led everyone in the slum to resist demolition and returned with a broom in the Milan Cathedral, have certain similarities in casting, not to mention the two films in terms of scene, theme, and character relationship. of various coincidences. De Sica described The Miracle of Milan as "completely a fairy tale, a fable, a Hans Christian Andersen story".

"Miracle of Milan" is adapted from Zavartini's novel "Toto the Good Man". It was completed after "The Bicycle Thief" and before "The Wind and Tears". Because of its fantasy color and fairy tale logic, it was summed up by the "trilogy". Paradoxically, he was isolated from that creative resume. But when we look at the film and re-enter the world of de Sica from this opening, the fable becomes ubiquitous, stabilizing as a form of understanding for all these delicate short stories of reality. In De Sica's seemingly different works, the stories of mad men and women, poor and lowly married couples, those of children, and the stories of the elderly, all come together into one chapter, linking up with various themes of war, history, nation and culture from time to time. , have become a kind of microcosm of post-war Italy, post-war Europe, and of course all of humanity. In "Italian Marriage", Sophia Loren put three children in front of Mastroianni, using allegories in literary classics. The young couple in "The Roof" spends the entire film building an "illegal" hut with a missing roof. De Sica's positive beliefs lead to pessimism about reality. The sentimental retreat in his character is manifested as insightful and vicious tongues in interviews. He uses movies to deduce his contradictory attitude towards human life. The destruction of people in suffering and the value of life developed by the destruction are presented at the same time. They cannot escape the fateful situation and are always looking for some kind of "unity" to save them. But unity and intimacy are often short-lived. Beyond unity, there is the irreconcilability between people and the egoism of each character (even animals) towards survival.

The bitter reality of struggling to survive that de Sica perceives applies equally to his personal career as a director. He was always having a hard time filming. He was "begging" for investment and couldn't get it. The most outstanding films were made by himself. After "Wind Candle and Tears", he had to compromise with reality. In the tug of war with the environment, he made films that were not so realistic, such as for the producer and the producer's girlfriends, Selznick and Jennifer Jones, Carlo Ponty and Sophia Loren. He even wasted years in Hollywood looking for investment to no avail. In the witty and insightful Italian comedies and romantic melodramas that followed, we can of course still find the unique brushstrokes of De Sica, whose genius shines in like sunlight from an empty roof window (and, These movies really make money). He may have never been satisfied with these works with strong industrialization and industrialization. But as a director, you always have to keep shooting, right? In this way, those characters who are struggling to find a place to live seem to have become a sentimental fable about the dignity of the film master.

Originally Posted in Beiqing Art Review

View more about Bicycle Thieves reviews