Like Bruce Beresford, Michael Mann might claim to be slightly other than the “typical” Hollyoood director, though he is Chicago-born and works a little more comfortably within American genres and conventions. But his apprenticeship includes a BA in literature from University of Wisconsin and a film degree from the prestigious London Film School. Returning to the USA in the1970s, he moved smoothly into commercial advertising where, like Ridley (Blade Runner) Scott, he quickly claimed distinction for his remarkable sense of lighting and décor. By the early 1980s he had segued off into television, gaining fame as the executive producer of a popular and long-running investigative crime drama, Miami Vice.The series established the city of Miami as the new site of “film noir” and its impact on the industry is still visible in contemporary shows like Miami CSI and The Glades. Lots of neon, lots of light on water, lots of with-it music.

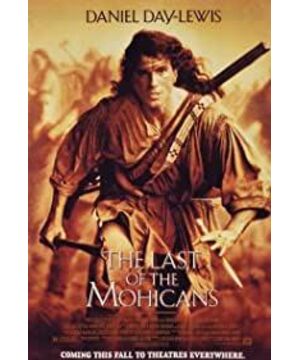

Frequently, directors who gravitate towards television sink below the horizon and are never heard from again. Mann was spared this fate because his skills-set fit nicely with the popular neo-noir revival of the 1980s and 1990s, to which he contributed Manhunter (1983 ). LA Takedown (1986) and Heat (1995), and The Insider (1999). In the new millennium Mann would add Miami Vice (2006) and Public Enemies (2009) to his screen credits: the first is a film vaguely evolved from the television series of the 1980s and the second a reprise of the 1930s gangster film, built around the figure of John Dillinger. It has never done any harm to Mann's career that he is also a capable screenwriter and a competent business manager with a knack for collecting first-class theatrical talent (think, Al Pacino, Robert DeNiro, and Russell Crowe, among others).Though his proven achievements would seem to best suit him for films with contemporary, urban settings and accents of the thriller, it didn't surprise too many people when he was contracted to direct The Last of the Mohicans (1992), the sixth remake of James Fenimore Cooper's novel of the same name, the favorite narrative of “Leather-Stocking Tales,” which founded the western genre in the 1820s.

As in Black Robe, we have in Last of the Mohicans a narrative of the earlier American west, when the “frontier” began on the northwest outskirts of New York City. We are now slightly more than 100 years downstream from the period of the Jesuit chronicles, but the war we are plunged into is the same world-historical battle between the empires of France and Britain for the control of North America. Now in its final phase, a seven-year encounter which in the USA is called the French/ Indian War (1756-63), this protracted battle leaves Britain the master of the continent, but also brings to the world stage a new set of actors who are beginning to call themselves “Americans,” and even remarking, quietly and hesitantly still, that they might prefer not to be servants of the English crown. The tribal tensions remain much the same:the Indians south of Lake Ontario (the Iroquois and the Mohicans) are allied with the English; the Algonquins and the Hurons, both north of the lake, take their marching orders from the French. A little incongruously, the Mohicans are tribal kin of the Algonquins, as indicated by their language, and bear no great love for the Iroquois. But the Iroquois Confederacy, the most powerful Native American political force of New York and New England, pursued a policy of “assimilation,” which forcibly drew members of other tribes into their own, sometimes effectively erasing the tribe's original identity. Hence the dire threat state to the Mohicans, which gives Cooper the title of his novel.take their marching orders from the French. A little incongruously, the Mohicans are tribal kin of the Algonquins, as indicated by their language, and bear no great love for the Iroquois. But the Iroquois Confederacy, the most powerful Native American political force of New York and New England, pursued a policy of “assimilation,” which forcibly drew members of other tribes into their own, sometimes effectively erasing the tribe's original identity. Hence the dire threat state to the Mohicans, which gives Cooper the title of his novel.take their marching orders from the French. A little incongruously, the Mohicans are tribal kin of the Algonquins, as indicated by their language, and bear no great love for the Iroquois. But the Iroquois Confederacy, the most powerful Native American political force of New York and New England, pursued a policy of “assimilation,” which forcibly drew members of other tribes into their own, sometimes effectively erasing the tribe's original identity. Hence the dire threat state to the Mohicans, which gives Cooper the title of his novel.”Which forcibly drew members of other tribes into their own, sometimes effectively erasing the tribe's original identity. Hence the dire threat state to the Mohicans, which gives Cooper the title of his novel.”Which forcibly drew members of other tribes into their own, sometimes effectively erasing the tribe's original identity. Hence the dire threat state to the Mohicans, which gives Cooper the title of his novel.

Fenimore Cooper, of course, is much more invested in these historical events than Michael Mann. The creator of “Leather Stocking” belongs to the first generation of post-revolution Americans: he was born in 1789, virtually at the outset of Washington's first term as President. And one of the crucial events of Cooper's teenage years was the journey of Lewis and Clark up the Missouri river to map the land acquired in the Louisiana Purchase. More to the point, perhaps, is that he was growing up during the second war with Britain (1812-14), in which the USA had decisively defeated English forces in the west. A decade later, just three years before the publication of Cooper's novel, President Monroe sent to Congress a message known as the Monroe Doctrine,which decisively asserts the claims of American nationalism against all the European powers. Cooper writes out of this intensely nationalistic milieu, but is aware of some of its complexity, working very self-consciously with issues of race and ethnicity. What place, if any, do the native peoples have in the new nation? How have they contributed to the creation of a unique American sensibility? How do we gracefully invite them to leave the land to us? As you will see in our small excerpt from the novel, Cooper struggles with these questions, finding them a bit awkward.do the native peoples have in the new nation? How have they contributed to the creation of a unique American sensibility? How do we gracefully invite them to leave the land to us? As you will see in our small excerpt from the novel, Cooper struggles with these questions, finding them a bit awkward.do the native peoples have in the new nation? How have they contributed to the creation of a unique American sensibility? How do we gracefully invite them to leave the land to us? As you will see in our small excerpt from the novel, Cooper struggles with these questions, finding them a bit awkward.

Mann is far less interested in American history and operates at a much lower level of political fervor. You might notice, for example, that Nathaniel, the archetypal American, turns out to be the British actor Daniel Day Lewis, who manages somehow to look pretty authentic in the costume of a backwoodsman. Mann handles the Native Americans differently as well, nodding appreciatively towards their value system but excluding them from real relevance. Interestingly, the film was released in the same year that marked the 500th anniversary of Columbus' first voyage , which caused it to be charged in some circles with “cultural imperialism.” That's a matter we will almost certainly discuss in class. What also seems reasonably certain is that Mann tries strenuously to reduce the political concerns of the novel and replace them with a love story.But as with other purveyors of western myth, the love story has an added dimension. We are really being invited to fall in love with the American west.

View more about The Last of the Mohicans reviews