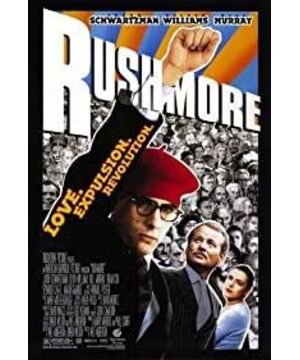

Before Wes Anderson's first film, "Bottled Rockets," he worked with Owen Wilson to write the script for "Youth and Youth". The inspiration for "Youth" is actually Roald Dahl, an outstanding British children's literature writer. The purpose of Wes Anderson and Owen Wilson in making this film is also to create their own "somewhat like the reality of Roald Dahl's children's books." Roald Dahl had a profound influence on Wes Anderson. He even adapted a book by Roald Dahl in 2009: "Fantastic Mr. Fox".

Anderson's Elder Muse-Bill Murray

In this movie, Wes Anderson meets his own older version of the muse-Bill Murray. In more than two decades of films, Wes Anderson has formed a core team relationship with many people, creating a close film family. Among them, Bill Murray had a profound influence on him. Since the beginning of "Youth", Wes Anderson has had Bill Murray's figure or voice in every work-even in "The Great Fox Papa" and "Island of Dogs", Bill Murray also contributed Has his own voice acting.

Bill Murray's career began in TV shows in the late 1970s, the most famous of which was "Saturday Night Live", which appeared in feature films only after that. Prior to working with Wes Anderson, Bill Murray had hardly received nominations or awards. Among them, his most well-known role should be the role in the famous one-day cycle movie "Groundhog Day". Most of his characters have both humorous and serious elements, discussing themes in a rational or philosophical way. Film critic Pauline Kyle summed up Murray’s comedic charm during this period. He said: “We like Murray because of his weirdness, because he seems to be fundamentally untrustworthy. Some souls.” Crap "It's great to let him know how to work."

Bill Murray's "crappiness" continued into the late 1990s, until his attention turned to projects like "Youth and Younger". In Wes Anderson's films, Murray's "crappy" contrasts with the meticulous scheduling in Anderson's films, and he becomes an unbalanced but compelling element in his own cinematic universe. Although Bill Murray’s character in Anderson’s films is based on his previous works, Anderson has made subtle and significant changes to his role, which has also led other directors to adopt this modification since then. Anderson pushed Murray's role beyond the general Hollywood comedy scene and focused on the struggles involving family, love, and finding one's identity.

Bill Murray was a great help to Wes Anderson, taking the production process of "Young and Young" as an example. On the first day of photography, Wes Anderson quietly instructed Bill Murray to make his work with the actors awesome. In public, Murray graciously listened to Anderson's advice and helped deliver the equipment. When Disney denied that a helicopter scene would cost $75,000, he gave Anderson a check to pay for the cost.

The preciseness of the script of "Youth and Youth" convinced Bill Murray to participate in the development of the film. He firmly believed that the script did not need his comedic characteristics to be enhanced by the character. Murray explained to others that the script "was very precise and Wes Anderson knew exactly what he was doing. He knew exactly what he wanted to do, exactly how he wanted each scene. I never Have really seen such a precise script. I will be confident of anyone who can write such a good one."

Murray's performance in "Youth and Youth" is so clear that it hits the root of his role. Like almost all Murray-like characters, Herman Bloom is in pain. "Youth and Youth" does everything possible to determine why Herman Bloom is sad: he is depressed with his marriage, despise his son, and despite a series of achievements, he still feels the emptiness of life. Then, he found an incredible antidote to this middle-aged crisis: befriend his son’s precocious classmate Max Fisher, and complete the reenactment and resolution of the crisis with him.

The reappearance and dissolution of mourning

In adolescence, Max Fisher is an adult who strives to grow up, and Herman Bloom is like a teenager with stunted growth. This mismatch between identity and appearance always symbolizes the traumatic moments encountered by the characters in the movie: Max Fisher has lost his mother, and Herman Bloom is immersed in a midlife crisis.

The theme of trauma is always present in each of Wes Anderson’s movies. The protagonist has either suffered a substantial absence from his relatives ("Moonrise Kingdom") or felt a crisis of age ("Aquatic Life" "Amazing" "Papa Fox"). In fact, Wes Anderson's movie style reproduces the depressed mood of the protagonist in the movie to some extent. The calm emotions in Wes Anderson's films are the emotional manifestation of the protagonist's crisis. The texture with high brightness and low saturation embeds and reveals this emotion.

In each of Wes Anderson's films, he guides his character through the beginning of mourning, repetition and dissolution with a different focus. In "Youth", Max Fisher mourns for his mother. His poor performance in school classrooms and extracurricular activities show that he is trying to get rid of the grief but can't get rid of the pain. The type of drama selected by Marx Fisher in the film reflects his precocity that is not in line with his age, while the year-long friendship between Herman Bloom and Max Fisher reflects the influence of adults under the influence of mental trauma. Attempt to return to childhood. The attitude reflected by this friendship creates an ageless space. The different traumas of the two have eliminated the age gap. In this space, people of different ages can even interact with each other with great empathy.

In Michael Charpin's "Wes Anderson's World", it was pointed out: "Sooner or later everyone will receive a thorough and broken education." Chris Robb, in "Wes Anderson, Masculinity, and the Crisis of the Patriarch", believes that the masculinity of male characters in Wes Anderson's movies reflects the compensatory behavior that they cannot mourn when they lose their loved ones. Therefore, the main behavior of the characters in Wes Anderson's movies can be summarized in one word: mourning.

Chris Robert quoted Freud's statement that mourning can only happen after the memories related to the object being mourned are recalled and examined. In Anderson's movies, the broken-hearted characters always tend to mourn the lack in the form of objects. In Susan Stewart's OnLonging: Narratives of the Miniature, Gigantic, Souvenir, the Collection (OnLonging: Narratives of the Miniature, Gigantic, Souvenir, the Collection), an object theory related to our sense of yearning is proposed. He also made a special distinction between objects used as souvenirs and objects used as collections, thinking that "the space of collection is a complex interaction of exposure and concealment, organization and chaos."

The bird's-eye view shots in Wes Anderson's films are often praised, and the shots are often full of rich details to entice the audience to study. The display of such collection objects can be regarded as miniaturization of the mourning process. Anderson expresses the emotions of the characters in the form of concrete objects in these shots, so that the psychological state of the characters is presented in the form of miniaturization. His attention to the collection of objects actually shows the characters, the process of the characters getting along with the trauma and the status quo that they have not yet recovered from the trauma.

Naturally, the appearance of mourning is often accompanied by the repetition and dissolution of mourning. In "Beyond the Pleasure Principle", Freud pointed out the repetitive nature inherent in trauma. After experiencing traumatic events, because of the lack of traumatic events, people tend to fall back into the trauma and experience repeated events again and again. This kind of ignorant repetition is often a sign of trauma, and in Wes Anderson's movies you can always see such recurring moments, where the characters hurt each other unknowingly. Cathy Caruth called it: "Trauma is not only a repetition of missing death, but also a repetition of survival."

According to Freud’s Mourning and Melancholia (Mourning and Melancholia), the subject in Wes Anderson’s movie can only complete the mourning after the object of the old love is replaced and the object of the new love is obtained and interrogated. Dissolution of the process. In "Youth and Youth", this dissolution is arranged as the last stage play of the movie. In fact, at the beginning of the film, theater and film were integrated together. Tom Gunning once put forward the concept of " attractive film " in the early 20th century to summarize the characteristics of a non-narrative film: this kind of film directly appeals to the audience's attention and stimulates the audience's senses through exciting spectacles .

Although Wes Anderson's films are not similar to the non-narrative sideshow films when the film first appeared, they still attract the audience through theatrical lens, and their selling points are also focused on color or balanced composition. Under this kind of "attractive movie", movie audiences are like theater audiences, enjoying the amazing performances on stage, and in the movie, it is assumed that the stage's "play in play" structure expresses what the movie shows. The longing for the existence of things is concretely expressed in this movie as the reappearance of mourning.

The stage play "Heaven and Hell" at the end of the movie is actually the protagonist's embodiment of his own inner life. Just like the bird's-eye view of Wes Anderson's movie shows memorabilia of trauma, Max Fisher embodies the contradictions in life. In this stage play. The Rushmore School Gymnasium in "Youth and Youth" has become a place where all adults and children gather to watch comedy and their plight. The drama is endowed with the characteristics of mourning, and the repetition of mourning is performed on the stage. They watch and witness the repetition of their mourning. Through this paradigm, Max Fisher not only managed to escape the shadow of his mother’s death, but also led the others in the gym through his trauma: Max returned to his adolescence, and Bloom walked in. Love relationship.

As Devin Allgron wrote in "LaCamera-Crayola: Authorship Comes of Age in the Cinema of Wes Anderson": "Max’s drama has surpassed plagiarism or monotonous fireworks. , But it affects the formation of the real community. The celebration scene after the play is Max’s real work. Wes Anderson slowed down the picture when the play was about to end, the camera stretched for a moment, slowly moved backward, This family is reflected in the picture frame."

Concluding remarks

Max Fisher said in "Youth and Youth": "I have been going to sea for a long time." Each of Anderson's films has characters who can be metaphorically gone to sea. They lost themselves in loss and trauma. These people include Anthony Adams in "Bottled Rockets", Rich Tienbaum in "The Genius", Steve Zisu from "Aquatic Life", and the fox in "The Great Papa Fox" .

In these movies, the characters eventually find a way to go beyond mourning in some way. In "Youth and Youth" or "Moonrise Kingdom", this method is presented in the form of a stage play. The stage in the movie allows the people in the audience to finally see the things that were ignored or lost in the mourning process, and to form a space for love with others. And Wes Anderson uses slow motion to condense this space of love on the screen forever.

View more about Rushmore reviews