I have a friend who refuses to know anything about the filming process, saying it would confuse her, unable to imagine how actors move between the inside and the outside of the film, the real and the fake.

Her exclamation was particularly sympathetic to me. There's always a part of my brain that refuses to admit that my favorite movies are fiction. (Even if Wenders himself hits my head with a sledgehammer, don't make me accept that the angels of "Under the Berlin Sky" don't exist.) All art forms have a mask that separates the artificial world from the real world. , the intermittent shooting and laying scenes are covered by skillful hands into a smooth and real picture. The process is not much different from pulling a rabbit out of a hat. No wonder former magician Georges Méliès was the first to realize the conjuring nature of the movie, waving a handkerchief and sending the spacecraft into space.

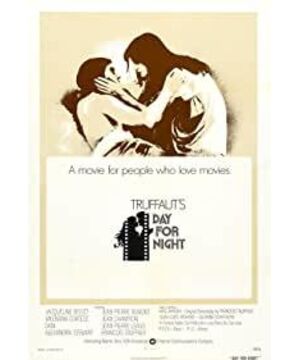

Movies, like all magic, run the risk of reducing the wonderful to boring when the mystery is uncovered. The male and female protagonists of the love story are like fire and water, and the unforgettable open ending is only because the director has no money to shoot the last scene... The audience must have a good brain to distinguish, in order to forget the gossip and let the movie run on its own. The most precious thing about Truffaut's Day by Night is that, despite its best efforts to penetrate the surface of filmmaking, it retains its ineffable magic at the same time.

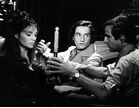

Let's look at the first shot of "Day to Night": the camera follows the hero (played by Jean-Pierre Leaud) out of the underground passage, through the crowds in the square, and stops at a middle-aged man. In front of him, he raised his hand to slap the man in the face, and his palm stayed in the air. "Cut", the screen quickly cuts to the director's close-up (played by Truffaut himself). Then cut back to the previous picture. This time we saw all kinds of studio staff, some of which were doing makeup for the male lead, and some arranged for extras to be in place. After everyone was in their places, the long shot was staged again. But this time we can hear the director's shouts, "Ladies with dogs, please hurry up" and "Get ready for the red car". So faced with the same picture, our attention goes from "what happens next" to "how this happens".

It's an extremely fluid and effective opening, with Hitchcock-esque simplicity. (Nanni Moretti's "My Mother" almost repeats this sequence at the beginning, with a different emphasis.) The next film revolves around the difficult filming of "Meet Pamela." This may be the best time for Truffaut's ability to schedule group dramas, especially for scene notes, makeup, and stunt performers, which are rarely seen outside of documentaries and books. Accurate and loving depictions of crucial characters.

Near the end of the film, an unexpected death occurs. In the voiceover that follows, the director describes the tragedy as "the end of the studio system", "movies like 'Meet Pamela' will never exist, films will be shot on the street, hand-held Shooting." Here, we were able to understand more clearly what Truffaut had in mind. Traditional Hollywood studios squeeze countless talented directors into money-making tools and give them the opportunity to create countless masterpieces, which is a love-hate relationship. It's an elegy to the dying American studio system and all those working behind the scenes. (The film is dedicated to Lillan Lish and Dorothy Lish, two of D.W. Griffith's greatest silent film actresses.)

It is precisely this kind of naive nostalgia that makes "Day to Night" received a lot of criticism. Famous film critic Pauline Kael wrote mercilessly: "Trüffaut's love for the mode of filmmaking that 'Meet Pamela' represents is beyond me." Compared with Jean-Luc Godard's reaction, It's just a bit of a mosquito bite. The two former friends have drifted apart after the 68 years of turmoil. Godard still emphasized the political and aggressive nature of the film, while Truffaut continued Hitchcock's influence and gradually embraced the mainstream.

One summer night in 1973, Godard walked out of the screening of "Day to Night" and wrote angrily to Truffaut, accusing him of being a liar, "You say that movies are like trains running in the dark, but who is Passengers? Which carriage (class) is he sitting in? Who is driving this train, with the informant of the management standing beside him?" To this, Truffaut replied with a 20-page long letter, which will contain years of grievances. Spit out fast, so I won't go into details here. If you are interested, you might as well come and read it. After that, the two new wave good (base) friends completely parted ways, which is embarrassing.

Returning to Day by Night itself, the ideological critiques of both Godard and Pauline Kael somewhat miss the point. It doesn't matter what kind of film "Meet Pamela" is, the joy of making a film—good or bad, difficult or easy—and the strong and fragile connection between people is what Truffaut praises Core. "Day to Night" has no intention of becoming "Contempt" any more than he has no intention of pursuing provocation and political change. It's a tiny time capsule filled with the fleeting and splendid happiness that movies bring. Perfect for winter viewing.

View more about Day for Night reviews