Orson Welles decided in 1958 to leave the United States for good and go into self-imposed exile in Europe. From there, Wells's work has tilted towards the perception of evil and good through his own experience. From "Citizen Kane" to "Miss Shanghai", he has more or less equal views on the ugliness and the good in human life. He believes that there are evil people in life, but they are not evil by nature, and the good and beautiful things in human nature can still be found in them. Whether it's Kane or George Minafer ("Ambersons"), Elsa or Arthur Banister ("Miss Shanghai"), there is still a side of sympathy or pity. However, from "Mr. Akatin" onwards, the pessimism intensified. Wells said, "Please note that there are two kinds of people in the world: givers and takers, the former who give generously and the latter who demand freely." Akatin is the "scorpion" in life, his nature is to sting those around him, so he must stay true to his nature. This approach to fatalism was confirmed again in "The Trial" shortly after "Mr. Arcadine." "I think he's guilty because he's a human being," Wells said of the unprovoked protagonist Joseph K. Wells was completely engrossed in original sin consciousness.

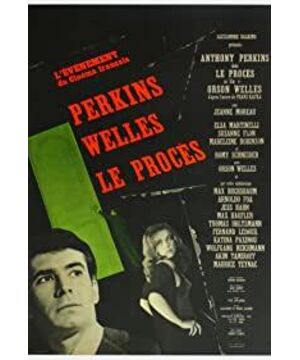

Wells' self-imposed exile is a Kafkaesque punishment-seeking process. This may be what makes him identify with the protagonists in Kafka's world. What happened to Joseph K. may seem absurd, but in Kafka's world, it was the reality of human existence, and it was confirmed in Wells' own experience. Wells had been seriously considering an adaptation of The Trial since 1960. He spent six weeks writing the script, but due to lack of funds, the actual shooting took nearly two years.

Wells may be the perfect person to bring Kafka's harrowing novel to the screen. The strong chiaroscuro, poignant humor and labyrinthine obscurity of his past works are all reminiscent of Kafka's fictional world. But unexpectedly, after the film was released, it attracted fierce criticism from British and American film critics. A fair evaluation of the film "The Trial" was only possible after a better understanding of Welles' intentions and connection to the ideological journey of Welles' film became possible.

The almost unanimous denunciation of the film by the British and American film critics at the time did not lie in the film's lack of respect for the plot development process and sequence of events of the original work. In this respect there can be practically no question of fidelity. The original novel was compiled and published by Max Broder after Kafka's death. Kafka's original manuscript has no chapter order. Most likely because Kafka believed that K's experience was originally a chaotic nightmare, and that there was no single plausible timing. According to a comparative study by a French critic, Wells changed Brode's order of chapters to: 1, 4, 2, 5, 6, 3, 8, 7, 9, 10.

The film was attacked for two main reasons. One is that the filming is too obscure and dull. Reading Kafka's novels is inherently easy to "go into the fog", but films are even more difficult to understand than novels. Second, Wells rewrote Kafka's "anti-hero" - helpless in the face of the absurd existence of man - into a "sinner" who still had the courage to resist. K's generous statement in court is considered an "unprobable" fiction, out of step with the Kafkaesque world of the film's opening. K escaped being stabbed to death by the executioner in the novel (which should be the logical ending), and in that less than one second shot, he grabs an object (a stone, or that bunch of explosives?) and throws it Going out, no matter how obscure it is, leaves a ray of hope for people after all.

Obscureness is one of the inherent characteristics of Western modernist works. If the film "Trial" tells the traditional story of an innocent man being persecuted innocently, the criticism it will attract is bound to be more serious. In the film, the whole world is indeed full of unrealistic colors. In gigantic offices with hundreds of typewriters, labyrinthine bank buildings, barristers' misty, candlelit bedrooms, Leni's papers-stuffed rooms, mysterious court halls, Titorelli's everywhere The dilapidated studio with the peeping eyes of a girl...all seemed "extremely unreal". This is a conscious affront to Kafka's style. As the British film critic Ei Stein pointed out, "Kafka's novels represent a fairly real world, but inhabited by fantasy people, in Wells' films real people inhabit it. in a nightmare world".

An adaptor making substantial changes to the original is acceptable if there are compelling reasons for that. Nine out of ten feature films from all over the world are adaptations. As an unwritten general rule, people never, and cannot, reassess the value of the original based on the success or failure of the adaptation. Conversely, an adaptation can have a new quality and value of its own. In fact, the film "The Trial" is just such an example.

Essentially, The Trial is a transformation of Kafka's ironic, impersonal world of despair into Wells' morality drama. When K announced to the barrister, "I have always wanted to be a martyr" and "I am a member of society", when he challenged the priest, he told the priest that he would be "responsible" for everything he did , "I am not your child," Wells criticized not only Kafka, but also some of the irrational tendencies instilled in the public by modernist art (such as the drama of the absurd) in the early 1960s. Wells elevates Kafka's nightmares into conscious dissections in one fell swoop. It is inevitable that he will change the final outcome of K.

Judging from all of Wells' films, he is more of a calm spectator of the world. He is more interested in the psychological state of the oppressor than in the distressed mood of the oppressed. He claimed to be an "Edwardian" (ie old-fashioned) rather than a "modern" intellectual. He clings to the nineteenth-century literary belief that literature should point people to certain bright futures. In The Trial, it is this essentially humanistic tradition's resistance to modernist values that drives him to reshape Kafka's "anti-hero", even if the modification almost undermines the work's logic.

Wells' modification of Kafka also has reasons for its historical background. He explained why the novel's ending had become unacceptable in 1962 in an interview with the French film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma following the release of The Trial. He said: "I think of The Trial as a 'ballet' written by a Jewish intellectual before Hitler came to power. After 6 million Jews were killed, Kafka would never have written that. In my opinion , those are all events before the existence of Auschwitz. I don't think my ending is that good, but it is the only possible ending." He also said that in the original "Joseph K. Evil is inseparable. He did not commit the crimes for which he was charged, but he was still guilty: he belonged to a sinful society, and he cooperated with it.” Therefore, if K continues to be a passive collaborator, "it is tantamount to implying that Hitler is indispensable". Wells may have exaggerated the issue, but his attack on irrational tendencies such as "life is absurd" and "people will be transported by life's conveyor belt to an unknowable end" is undoubtedly sincere and valuable.

Now that Joseph K. has changed from a "dream man" to a "real man" (Wells adapted the story about the door of the law told by the priest in the second half of the original book into what was in K's dream at the beginning of the film). see, and let the police wake him up), the derealization of the setting of the story becomes a necessity, since it is, after all, a fable, based on a novel by... Kafka. Wells said he couldn't afford to travel to Yugoslavia to use a set designed for the film because of financial difficulties, and had to scribble a set in an abandoned train station in Paris. His original design was actually more abstract than it actually was: "My original idea was for the set to fade away. The elements of realism should fade away, before the viewer's eyes, leaving only a wilderness, as if everything was reduced to Nothing.” We can still vaguely see this conception in the finished film: as Joseph K.’s psychological tension grows, the locations of the various events move miraculously closer to each other, the walls disappear, and at the end of the corridor , opening a door will lead to another location. The concrete and real environment is unrealistically connected, until a wilderness appears at the end of the film, and everything disappears in the sound of explosions.

If you watch this movie for entertainment purposes, you will find it obscure, dull, and difficult to finish. If you have serious expectations of artistic appreciation, you will develop a keen interest in this film, applying different standards of appreciation to different quality films, which is a matter of course.

View more about The Trial reviews