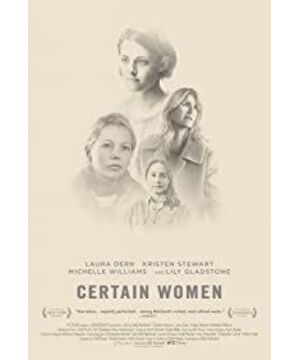

Translated from "Both Ways is the Only Way I Want It" by Mailie Meloy

The Chinese version "Best of Both Worlds " of the original book "Both Ways Is The Only Way I Want It" has been released. This article is a translation of the original draft, which is different from the version in the book.

When the movie was approved, I saw the first short story, which happened to be the story played by Kristen Stewart. I liked this subtle secret love story very much at the time. The character of Richter in the original book was a boy, but I didn't expect it to be changed to a girl in the movie, so I translated this. "Beth Travis"

Chet Morgan grew up in Logan, Montana, at a time when children rarely suffered from polio. But in Logan City, the disease is still common. Chet Morgan suffered from polio before he was two years old. Although he was cured, his right hip and hip never fully developed, so his mother always felt that he would not live long. Chet began learning to ride horses at the age of 14 as a way to prove to his mother what he was capable of. Chet discovered that horses kick or startle not because they are so cruel by nature, but because over millions of years of evolution, horses have developed this instinct to move fast, otherwise they would just become The lion's plate. Chet told his father what he had found, but his father only said, "You still mean it because they are." He couldn't explain it, but he thought Dad was wrong. He himself felt that there was a difference between the two, and that what people called "savage nature" was nothing like what he had personally experienced from horses. Chet was small but stocky, but his diseased hips made getting on and off a horse a challenge. Before he turned 18, he had problems with his right knee, right foot and left femur. Dad drove him to Great Falls, where doctors placed a plate on his normal leg, extending from hip to knee. Since then, he has walked like someone who is always asking himself questions. His mother was 3/4 Cheyenne and his father was a stubborn Irishman. Chet's stature was inherited from his mother. His parents had unrealistic dreams for their son's growth, but didn't know how to achieve them. His older brother went to join the army, and as Chet watched his older brother embark on a journey eastward, slender and handsome in uniform, he couldn't help but wonder, why did God and fate favor his older brother so much? Why is the opportunity so unfair? At the age of 20, Chet left home and headed north. Over the winter, he helps feed the cows on a farm outside Le Havre, where the family usually lives in the city and their children are already in school. When the roads weren't covered in snow, Chet would go to the nearest neighbor's house and play a few games of poker. But most of the time, the snow kept him home alone. He has plenty of food to eat, and the TV has a good signal. He also has a lot of women's magazines, and he knows far more about them than he knows about real women. For his 21st birthday, he was wearing long pajama pants, two flannel shirts and a winter coat, warming a bowl of soup on the stove. That winter, he suddenly worried about himself. He felt that if he went on alone like this again, there would always be some danger. In the spring, he found a new job in Billings, serving coffee in the office and chatting with friendly other secretaries about athletics and sports news. They liked Chet and offered to let him work in their Chicago office. He went back to his rented room, pacing back and forth dragging his stiff hips. He figured it out, if he wants to sit in the office every day, within three years, he will have to use a wheelchair. So he quit his job and packed all his stuff. He was nearly penniless, and the pain in his hip was about to eat him up. That winter, he found another job feeding animals in Glendive, near the North Dakota border. Instead of heading north, he considered turning east, where it might not snow as often. He lives in a cubicle in the barn with a TV, a sofa, a stove and a refrigerator. At night, he could hear the sound of the horses in the stable. But he completely misjudged the weather, where snow began to fall in October, too. Relying on packages and letters from his mother, he held on until Christmas. But in January of the following year, his worries about himself resurfaced. This worry is not without reason. It was tension in his spine at first, but not a specific pain point. The farmer left him a truck with a heater. One evening, he warmed up the car and drove into the city despite the heavy snow. The cafe was still open, but he wasn't hungry. The gas station glowed a warm blue light, but the truck's tank was already full. He didn't know any poker players in town and didn't know what to do to pass the time. He had to get off the main road and drive aimlessly around the city when he happened to pass a school. The side doors of the school were lit, and people parked in the parking lot and entered the classrooms. He started to slow down, pulled over to the side of the road, and watched the students. Involuntarily, he stroked the steering wheel wrapped in a warm wool cover with his hands, and finally made up his mind to get out of the car. Raising his collar against the cold wind, he followed the crowd into the school. One classroom was lit, and the students he followed sat down at desks that were apparently too small, greeting each other. The walls are littered with paper building signs and photos, and the alphabet is cluttered on the blackboard. Most of the students here are his parents' age, but with significantly more relaxed faces and more city-like clothing—thin shoes and clean coats. He walked to the back of the classroom and found a seat. He took off his heavy denim jacket and checked his boots to make sure there were no stains left in the classroom. "We should find a high school classroom," a man said. A woman—a girl—stands on the podium and takes a few sheets of paper from a briefcase. She has light-colored curly hair and wears a gray wool skirt and blue sweater, with gold-trimmed glasses. She was thin and looked tired and nervous. Everyone was quiet, waiting for her to speak. "I've never taught," she said. "I don't know how to start. Would you like to introduce yourself?" The gray-haired woman said, "We all know each other." Another woman objected, "No. , she doesn't know us." "You can talk about what you know about school law first." The adults sitting at the students' desks looked at each other. "I don't think we know anything," someone said, "that's why we're here." The girl looked helpless, she hesitated for a few seconds, turned to the blackboard, and wrote "Adult Education" 302" and her name "Beth Tevez". The chalk creaked on the blackboard as the letters "H" and "R" were written. The students held back, an older The woman said: "If you held the chalk straight with your thumb to the side, it wouldn't make that noise. Beth Tevez blushed and changed the subject to talk about the application of state and federal law to the public school system. Chet found a pencil in her desk, using what the lady had said was a chalk-holder. The way to hold a pencil. He wondered to himself why no one had ever said that chalk was used this way when he was in school. The students started taking notes, and he sat in the back seat listening intently. Beth Travis seemed to be a lawyer. Chet's dad always joked about lawyers, but he never said there were women lawyers. Most of the teachers in the classroom were teachers, and the questions they asked were about the rights of students and parents, and Chet never thought about it. These issues. He never knew students had their own rights. His mother grew up in a parochial school in St. Xavier, where Indian students were beaten for not speaking English, even for no reason. He's a bit luckier. An English teacher once hit him on the head with a dictionary, and a math teacher smashed a ruler on his desk. But in general, his teachers didn't find him Once, Beth Tevez looked like she was going to ask him a question, but a teacher raised his hand to answer, and he was spared. At nine o'clock, the lesson was over, the teachers said to Miss Tevez Thanks, said she taught well. They talked to each other about where to go for a beer for a while. Chet felt he should stay and explain his behavior, so he still sat at his desk. Sitting too long, his hips Starting to feel stiff. Miss Travis packed her briefcase and put on a red down jacket that made her look like a balloon. "Are you going to stay?" she asked. "No, ma'am. "He got up from behind his desk. "Are you registered for this course?" " "No, ma'am." I just saw someone come in. "Are you interested in school law?" He thought about how to answer. "Before tonight, I didn't know anything about it." " She looked at the slender golden watch in her hand. "Is there a place to eat nearby?" she asked. "I have to drive back to Missoula tonight." This is the North Dakota border, and west along the interstate are Billings, Bozeman , and then where he grew up, Logan, and further west is Missoula, almost to the border of Idaho. "That's a long drive," he said. She shook her head, not in disapproval, but a little surprised. "I took the job before I finished law school," she said. "I just needed a job, and I was worried that my student loan deadline was coming up. I had no idea where Glendive was. Here it is. Literally looks a lot like Belgrade, which is not far from Missoula. I must have confused the two places. Didn't expect that not only did I get a formal job, but they also To get me here to work extra. It takes me nine and a half hours to get here. Now I have to drive another nine and a half hours back because I have work to do in the morning. I have never done a better job in my life. It's the dumber thing." "I can take you to the coffee shop," he said. Her expression seemed to wonder if she should be afraid of him, but she nodded anyway. "Okay," she said. As he walked in the parking lot, he was a little worried that she would notice that he wasn't walking right, but she didn't seem to take it to heart. She got into her yellow Dassam and followed his truck to the cafe on the main road. He thought she could find it herself, but he wanted to spend more time with her. The two walked into the cafe and sat down face to face. She ordered coffee, a turkey sandwich, and a brownie sundae, and asked the waiter to serve it all at once. He doesn't want to eat anything. Beth Travis took off her glasses and put them on the table, rubbing her eyes. "Did you grow up here?" she asked. "Did you know those teachers?" "No, ma'am." She put her glasses back on. "I'm only 25," she said. "Don't call me ma'am." He didn't speak. She is three years older than him. Under the light, her hair was the color of honey. She didn't wear a ring. "Did you just tell me why you came to class?" she asked. "I just saw everyone walking in." She stared at him, as if wondering if he might be a danger. But it was bright in the dining room, and he tried to look harmless. He knew he would not bring any danger, especially with other people, and it kept him from feeling sad and uneasy. "Am I making a fool of myself?" she asked. "No." "Will you continue to come to class?" "When's the next class?" "Thursday," she replied, "Every Tuesday and Thursday for nine weeks. Hey." She used her hand again Blindfolded. "What the hell am I doing?" He tried to think about how he could help her. He has to go back to take care of those cows, and driving to Missoula to pick her up is unlikely. Missoula was too far, and they had to drive back. "I didn't register for the class," he said finally. She shrugged. "No one's going to check." Her food was delivered, and she picked up the sandwich first. "I didn't even know school law," she said. "I had to study it myself before every class." She wiped the mustard from her chin. "Where do you work?" "Feed the cows at Hayden Ranch just outside the city. It's just a winter job." "Would you like the other half of a sandwich?" He shook his head. She pushed the plate aside and took a bite of the melted sundae. "If you can stay longer, I can show you around," he said. "Look at what?" "The ranch," he replied, "and the cows." "I have to go back, I have to work tomorrow morning." "Okay." She looked at her watch, "Oh my God, it's nine o'clock. It's 45." She quickly took a few bites of the sundae and down her coffee, "I have to go." He watched the taillights of the Dassam fade into the darkness, and then drove himself in the opposite direction. Thursday was not far from Tuesday, and it was almost Wednesday. He suddenly felt hungry, and when she sat across from him, he never felt hungry. He wished he had just accepted the half of the sandwich, but he was so shy. "Am I making a fool of myself?" she asked. "No." "Will you continue to come to class?" "When's the next class?" "Thursday," she replied, "Every Tuesday and Thursday for nine weeks. Hey." She used her hand again Blindfolded. "What the hell am I doing?" He tried to think about how he could help her. He has to go back to take care of those cows, and driving to Missoula to pick her up is unlikely. Missoula was too far, and they had to drive back. "I didn't register for the class," he said finally. She shrugged. "No one's going to check." Her food was delivered, and she picked up the sandwich first. "I didn't even know school law," she said. "I had to study it myself before every class." She wiped the mustard from her chin. "Where do you work?" "Feed the cows at Hayden Ranch just outside the city. It's just a winter job." "Would you like the other half of a sandwich?" He shook his head. She pushed the plate aside and took a bite of the melted sundae. "If you can stay longer, I can show you around," he said. "Look at what?" "The ranch," he replied, "and the cows." "I have to go back, I have to work tomorrow morning." "Okay." She looked at her watch, "Oh my God, it's nine o'clock. It's 45." She quickly took a few bites of the sundae and down her coffee, "I have to go." He watched the taillights of the Dassam fade into the darkness, and then drove himself in the opposite direction. Thursday was not far from Tuesday, and it was almost Wednesday. He suddenly felt hungry, and when she sat across from him, he never felt hungry. He wished he had just accepted the half of the sandwich, but he was so shy. "Am I making a fool of myself?" she asked. "No." "Will you continue to come to class?" "When's the next class?" "Thursday," she replied, "Every Tuesday and Thursday for nine weeks. Hey." She used her hand again Blindfolded. "What the hell am I doing?" He tried to think about how he could help her. He has to go back to take care of those cows, and driving to Missoula to pick her up is unlikely. Missoula was too far, and they had to drive back. "I didn't register for the class," he said finally. She shrugged. "No one's going to check." Her food was delivered, and she picked up the sandwich first. "I didn't even know school law," she said. "I had to study it myself before every class." She wiped the mustard from her chin. "Where do you work?" "Feed the cows at Hayden Ranch just outside the city. It's just a winter job." "Would you like the other half of a sandwich?" He shook his head. She pushed the plate aside and took a bite of the melted sundae. "If you can stay longer, I can show you around," he said. "Look at what?" "The ranch," he replied, "and the cows." "I have to go back, I have to work tomorrow morning." "Okay." She looked at her watch, "Oh my God, it's nine o'clock. It's 45." She quickly took a few bites of the sundae and down her coffee, "I have to go." He watched the taillights of the Dassam fade into the darkness, and then drove himself in the opposite direction. Thursday was not far from Tuesday, and it was almost Wednesday. He suddenly felt hungry, and when she sat across from him, he never felt hungry. He wished he had just accepted the half of the sandwich, but he was so shy. He tried to think how he could help her. He has to go back to take care of those cows, and driving to Missoula to pick her up is unlikely. Missoula was too far, and they had to drive back. "I didn't register for the class," he said finally. She shrugged. "No one's going to check." Her food was delivered, and she picked up the sandwich first. "I didn't even know school law," she said. "I had to study it myself before every class." She wiped the mustard from her chin. "Where do you work?" "Feed the cows at Hayden Ranch just outside the city. It's just a winter job." "Would you like the other half of a sandwich?" He shook his head. She pushed the plate aside and took a bite of the melted sundae. "If you can stay longer, I can show you around," he said. "Look at what?" "The ranch," he replied, "and the cows." "I have to go back, I have to work tomorrow morning." "Okay." She looked at her watch, "Oh my God, it's nine o'clock. It's 45." She quickly took a few bites of the sundae and down her coffee, "I have to go." He watched the taillights of the Dassam fade into the darkness, and then drove himself in the opposite direction. Thursday was not far from Tuesday, and it was almost Wednesday. He suddenly felt hungry, and when she sat across from him, he never felt hungry. He wished he had just accepted the half of the sandwich, but he was so shy. He tried to think how he could help her. He has to go back to take care of those cows, and driving to Missoula to pick her up is unlikely. Missoula was too far, and they had to drive back. "I didn't register for the class," he said finally. She shrugged. "No one's going to check." Her food was delivered, and she picked up the sandwich first. "I didn't even know school law," she said. "I had to study it myself before every class." She wiped the mustard from her chin. "Where do you work?" "Feed the cows at Hayden Ranch just outside the city. It's just a winter job." "Would you like the other half of a sandwich?" He shook his head. She pushed the plate aside and took a bite of the melted sundae. "If you can stay longer, I can show you around," he said. "Look at what?" "The ranch," he replied, "and the cows." "I have to go back, I have to work tomorrow morning." "Okay." She looked at her watch, "Oh my God, it's nine o'clock. It's 45." She quickly took a few bites of the sundae and down her coffee, "I have to go." He watched the taillights of the Dassam fade into the darkness, and then drove himself in the opposite direction. Thursday was not far from Tuesday, and it was almost Wednesday. He suddenly felt hungry, and when she sat across from him, he never felt hungry. He wished he had just accepted the half of the sandwich, but he was so shy. "If you can stay longer, I can show you around," he said. "Look at what?" "The ranch," he replied, "and the cows." "I have to go back, I have to work tomorrow morning." "Okay." She looked at her watch, "Oh my God, it's nine o'clock. It's 45." She quickly took a few bites of the sundae and down her coffee, "I have to go." He watched the taillights of the Dassam fade into the darkness, and then drove himself in the opposite direction. Thursday was not far from Tuesday, and it was almost Wednesday. He suddenly felt hungry, and when she sat across from him, he never felt hungry. He wished he had just accepted the half of the sandwich, but he was so shy. "If you can stay longer, I can show you around," he said. "Look at what?" "The ranch," he replied, "and the cows." "I have to go back, I have to work tomorrow morning." "Okay." She looked at her watch, "Oh my God, it's nine o'clock. It's 45." She quickly took a few bites of the sundae and down her coffee, "I have to go." He watched the taillights of the Dassam fade into the darkness, and then drove himself in the opposite direction. Thursday was not far from Tuesday, and it was almost Wednesday. He suddenly felt hungry, and when she sat across from him, he never felt hungry. He wished he had just accepted the half of the sandwich, but he was so shy.

On Thursday night, he arrived earlier than everyone else, watching from his truck. A teacher opened the side door with a key. As most of the students entered the classroom, Chet continued to take his seat in the back row. Beth Tevez came in with a tired face, taking off her coat as usual, and taking a few pages from her briefcase. She was wearing a turtleneck green sweater, jeans and black snow boots today. She came down to distribute the handout and nodded to him. She also looks good in jeans. The top of the handout reads: "Important High Court Decision Affecting School Law." He sat at the back of the classroom and looked at the people who raised their hands to answer, trying to imagine his former teacher sitting here too, but he couldn't. A man about Chet's age raised his hand to ask about a raise, but Beth Tevez replied that she was not a labor organizer and asked him to ask about the union. The older women in the classroom laughed and teased him. The class ended on time at nine o'clock, and the others went to drink beer, leaving him and Beth Tevez alone in the classroom. "I have to lock the door," she said. He spent 48 hours assuming they would go to dinner together, but now he doesn't know how. He never asked a girl to go anywhere. In high school, there were girls who would sympathize with him, but he never took advantage of it, either because he was shy or because he had too much self-esteem. He stood there awkwardly for a moment. "Are you going to the coffee shop?" he finally asked. "I'll probably only be there for five minutes." At the cafe, she asked the waiter for the fastest meal. The waiter brought her bread and soup, packed coffee, and brought the bill together. When the waiter left, she said, "I don't know your name yet." "Chet Morgan." She nodded as if he had said the right answer. "Do you know anyone here who can teach this class?" "I don't know anyone." "Can I ask what's wrong with your leg?" He was a little surprised, but he was willing to answer any question she asked. He told her the simplest answer: polio, horseback riding, broken bones. "So are you still riding now?" He said that if it wasn't for riding, he might be in a wheelchair or in a lunatic asylum by now. She nodded as if that was the correct answer, and looked out the window at the dimly lit street. "I was worried that I would finish law school and only get a job selling shoes," she said. "Sorry to keep bringing this up, I was thinking about the way home."

That weekend was the hardest weekend he's ever had. He fed the cows and cleaned the pasture. He brushed the horses' fur, and he felt that the horses were wondering what his purpose was. When he was done, he went back to his room and sat on the sofa, switching between the channels and turning off the TV. He was thinking about how he should be courteous, she was older than him, a lawyer, and lived almost on the other side of the state. He felt a strange feeling in his chest, but it wasn't the unease he used to have. Instead of driving, he rode into the city on Tuesday. It was a warm night for January, the sky was clear, and he could feel the breeze blowing in his face. Darkness spreads on all sides of the plain, only the city lights are still lit. He was watching the stars in the sky while he rode. He tethered his horse to the school's bicycle rack, which was far from the side door and some distance from the teachers' parking lot. He took a large bag of wheat out of his coat pocket, and the horse smelled it and began to taste it. "There's only so much I have left," he said, stuffing the empty plastic bag back into his pocket. The horse looked up and smelled the strange smell of the city. "Don't let yourself get stolen," Chet said. He saw that half of the people had come, and he followed into the classroom, and everyone sat back to where they were last week. They were chatting about the recent weather and wondering if the snow would melt soon. Beth Travis, still in her bloated down jacket, holds her briefcase. Seeing her, he was happier than he expected. She's still wearing jeans today, and he thinks it's fine, because he's a little bit afraid that she'll wear that wool dress again. She looked a little troubled today, and she didn't seem very willing to appear here. After class, when the others left, he asked, "Can I take you to the coffee shop?" "Oh..." she said, looking away from him. "Not in a truck," he said quickly, thinking that a truck might be more dangerous to women, possibly because it's a more enclosed space. "Come out and I'll show you," he said. He got off the horse and rode a few laps, realizing that he might look a little silly, but he was happy to show Beth Travis that he could ride like a normal person, and Beth stood there holding her briefcase. "My God," she said. "Don't be afraid," he said. "Give me your bag, and then give me your hand. Put your left foot on the pedal, and step over the other." She did so awkwardly, and he reached out and pulled her to the side. behind himself. He hung her briefcase on the saddle bridge, and she clutched his coat tightly, their legs pressed together. He could only notice how warm her body was, her warmth running down his spine. He parked the horse behind the café, followed her off the horse, handed her the briefcase, and tied the horse. She looked at him and laughed, and he realized that he had never seen her smile. She raised her eyebrows and opened her eyes wider when she laughed, instead of squinting like most people do when they smile. She looked surprised. In the cafe, the waiter brought a burger and fries in front of Beth Tevez and asked, "Does the chef want to know if it's your horse at the door?" Chet answered in the affirmative. "Can he give it some water?" He said he was grateful he was willing to do so. "Is the truck broken?" the waitress asked. He shook his head and said there was nothing wrong with his truck, and the attendant left. Beth Tevez turned the long side of the oval plate toward him and picked up the burger. "Eat some fries," she said. "How can you eat nothing all the time?" He wanted to say that as long as he was around her, he wouldn't feel hungry. But he was a little afraid to see her expression when he heard it, the expression she always had when she was shy. "Why are you afraid of a job selling shoes?" he asked. "Have you ever sold shoes, that's hell." "I mean, why are you afraid you can't get another job?" She stared at the burger, as if there were answers. The color of her eyes is close to that of her hair, and her eyes are wrapped in light-colored eyelashes. "I don't know," she said. "No, I actually do. Because my mom works in the school cafeteria, my sister works in the hospital laundry, and selling shoes is the best job a girl in my family can get." Where's your father?" "I don't know him." "It's a sad story." "No, it's not," she said. "It's a happy story. I'm a lawyer, right? With a fantastic job driving to work in fucking Glendive and every 15 minutes I'm questioning if I'm crazy." She put down her burger and covered her eyes with the back of her hands. Her fingers were greasy and one was dipped in ketchup. "It's ten o'clock," she said. "I won't be home until 7:30 tomorrow morning. There are a lot of deer on the road, and the banks of the Three Forks are still covered with black ice. If I can make it through, I'll have time to go home and take a shower. , then go to work at 8 and do those jobs no one wants to do. Then learn a little school law tomorrow night, drive here after lunch on Thursday, and can't keep your eyes open all the way. Maybe better than doing laundry in the hospital Better, but not much better." "I live very close to the Trident," he said. "Then you know the ice conditions there." He nodded. She wiped her fingers with a paper towel dipped in water and drank her coffee. "You're fine and willing to ride," she said. "Can you take me back to find my car?" He led her on again, this time around his waist. She seemed to fit right into his body, like a missing piece of a puzzle. He slowly rode back to the school parking lot, not wanting her to leave in his heart. He parked his horse beside the yellow Dassam and held her hand tightly as he helped her dismount. She tugged off the coat that she had tufted up while riding, and the two stood looking at each other. "Thank you," she said. He nodded. He wanted to kiss her, but had absolutely no idea how to do it. He really wished he had practiced, like with his former high school girl classmates, or the friendly secretary in the office, so he could be more prepared at this moment. She was about to say something, but he interrupted her nervously. "See you Thursday," he said. She hesitated, then nodded. He took it as a sign of encouragement. He took her hand again and kissed it because he really wanted to. Her hands were soft and cold. Then he leaned over and kissed her on the cheek, because that's what he wanted to do too. She didn't move, and when he was about to give him a real kiss, she seemed to come to her senses, took a step back, and pulled her hand out of his. "I have to go," she said, and opened the door. He led the horse and watched her drive out of the parking lot, then kicked the snow hard. The horse ducked. He wanted to jump up and down, out of a mix of happiness, anxiety and pain. He scared her away. He shouldn't have kissed her. He should have kissed her again. He shouldn't have interrupted her. He led the horse and watched her drive out of the parking lot, then kicked the snow hard. The horse ducked. He wanted to jump up and down, out of a mix of happiness, anxiety and pain. He scared her away. He shouldn't have kissed her. He should have kissed her again. He shouldn't have interrupted her.

Instead of playing funny cowboy tricks Thursday night, he had a serious mission: He would answer all her questions seriously, like why he didn't eat. He won't interrupt her again. This time he didn't wait for others to come and went straight into the classroom. But a man in a gray suit came in and stood behind the podium. "Miss Tevez," he said, "couldn't afford the time and effort to drive from Missoula, so I took the next class. I'm practicing here. As you may know, I'm recently divorced. , so I'm more free. That's why I'm here." The man on the podium was still talking, and Chet had stood up and walked out the door. He stood outside, breathing the cold air. He stared at the twinkling lights of the city until he blinked hard enough to make it clear before climbing into his truck. He knew that Beth Tevez lived in Missoula, 600 miles away, on the other side of the mountain. He didn't know where she worked or if she had her phone number in the Yellow Pages. He didn't know if he scared her away, or the fact that they were riding together scared her away. He didn't know if his truck would make it all the way to Missoula, or how the rancher would react when he found out he was gone. But he still drove in the direction out of the city, and he had watched the yellow Dassam car leave here three times. Straight roads rolled under truck wheels, snow-covered roads stretched into dark, silent spaces. He stopped for a while outside Mills, and for a while outside Billings, getting out of the car and walking around to ease his stiff legs until he could continue driving. Near Great Timber, the plains transformed into mountains, and towering black silhouettes could be seen under the stars. He refueled the car in Bozeman, drank a cup of coffee, and drove down the open road past Trinity and Logan. In some house in the darkness to his right, his parents were sleeping peacefully. It was still dark when he arrived in Missoula. He stopped at a gas station and looked for the name "Tevez" in the phone book. There was a name and phone number of "Tevez B" in the phone book, but no address. He took down the number, but didn't call it. He asked the cashier where the law firm was in the city, and the cashier shrugged and replied, "Maybe in the city center." "Where is that?" The cashier stared at him. "It's downtown," he said, pointing to his left. Chet drives into the city center, where shops, old brick houses and a one-way street are bathed in dawn light. Being so close to the mountains made him feel a little claustrophobic. When he finally saw a sign that said "law firm," he went in and asked the secretary who had just opened the door if he knew Beth Travis, the lawyer. The secretary looked at his twisted legs, his boots and his coat, then shook his head. The law firm of the second firm was friendlier. She called the law school and asked where Beth Tevez worked, then put her hand over the phone and said, "She teaches in Glendive." "She also has a job, in the city." The secretary explained the situation on the phone, wrote something down on a piece of paper and handed it to him. "Over at the old train station," she said, pointing her pencil in the direction of the window. He arrived at the address written on the paper at 8:30, just as Beth Travis pulled into the parking lot. He got out of the car, still uneasy. She was rummaging in her briefcase and didn't see him right away. Then she looked up. She looked at the truck behind her, then at him. "I drove over here," he said. "I thought I was in the wrong place," she said. "What are you doing here?" "I'll see you." She nodded slowly. He did his best to stand up straight, and she lived in a world completely different from his. It takes less time to fly to France or Hawaii than to drive here. She lives around lawyers, downtown and mountains. His life is of horses that starve in the morning, cows waiting in the snow, and he needs to drive 10 hours to go back to feed them. "I'm sorry you don't teach anymore," he said. "I'm looking forward to those nights." "It's not because..." she said, "I was going to tell you on Tuesday, when I applied for a teacher change. , because it's too time-consuming to drive. They found a substitute teacher yesterday." "Okay," he said, "it's a real pain in the ass." "Right?" A man in a black suit got out of the silver car, looked at them, and looked at Chet. Beth Travis waved and smiled at him. He nodded, glanced at Chet again, and walked into the office. Chet suddenly hoped that she resigned because of herself, that he could have a little influence on her life. She pulled her hair behind her ears, and he wanted to go forward and touch her hand. But he could only put his hands into the pockets of his jeans. "I have no ill will," he said. "Okay." "I've got to go back and feed the cows," he said. "I just think if I don't drive over, I'll never see you again, and I don't want that. Just that." She nodded. . He stood there waiting, expecting something from her, eager to hear her voice again. He still wanted to touch her, her arm, or just her wrist. She was still standing in the distance, waiting for him to leave. Finally he had to climb into the truck and start the engine. She was still standing there, watching him pull out of the parking lot as he hit the highway and left the city. For the first half hour, he held the steering wheel tightly, his knuckles white and his eyes fixed on the road devoured by truck wheels. He was too tired to be angry at all. He began to shut his eyes and almost went out of the way. He bought a cup of coffee in Boot City and finished it while standing by the truck. He wished he hadn't seen her in the parking lot right away, he wished he'd had a minute to get ready. He crushed the coffee cup and threw it aside. When passing by Logan, he wanted to stop for a while, but he knew what his parents would say to him. The mother would worry about his health, her ailing son risking his life by driving all night. "You don't even know that white girl," she would say. His dad would say, "Oh my God, Chet, are those horses without water all day?" He went back to Hayden Ranch and fed the horses with food and water, and they seemed all right. The horses carried hay without complaint, and he remembered the two-year-old pony he had when he was 14, kicking all over him all the time. The pain in his stomach now is exactly the same as when he was kicked by a horse. But Beth Tevez did nothing unfair to him, he didn't know what he was expecting. Even if she told him to stay, he still had to come back. It was the sense of ending contained in the conversation between the two, and the protective look of the man in the black suit when he looked at her, which made him feel sore and scarred all over. As he walked out of the barn, the moon had just risen and the fields were covered with a somber blue. His hips were stiff and sore. He wondered if his seriousness with Beth Tevez could plant a seed in her heart. She's not coming back, and it's hard to imagine her driving back again for any reason. But she knew where he lived. She is a lawyer and she can find him whenever she wants. But she won't. It pained him. He wants to develop with girls, and now that he has these experiences, he hopes it is just a drill. It was getting colder and he had to go back to the barn right away. He took the note with her phone number out of his pocket and watched it in the moonlight until he knew the number by heart. After that, he did what he was supposed to do, he rolled the note into a ball and threw it into the distance.

(Please do not reprint)

View more about Certain Women reviews