2. This experiment is very famous, but let’s talk about the basic content of the experimental design:

(1) The “superficial” theme of the experiment is: scientists want to understand how humans learn knowledge and what factors can improve the efficiency of human learning; In this experiment, the variable tested is "punishment". Does the greater the punishment, the higher the learning efficiency? (Of course, this is just a pretense)

(2) Each experiment includes three participants: a "Teacher": he/she is a volunteer, the real "subject" in the experiment. Another "Learner": He sits in another room, separated from the "Teacher" by a wall, and will receive the "Teacher"'s instructions and answer questions; the "Student" is also a volunteer on the surface, but in reality Above is the experimenter's accomplice. Finally, there is an "Experimenter": the person who sits behind the "teacher" and "supervises" the experiment. In experimental terms, the "experimenter" is the one who actually stimulates the experimental group.

(3) First, the "teacher" will read a set of words (such as "strong arm", "black curtain") to the "student", then he will read the first word and ask the "student" to choose the correct phrase combination. For example, if "teacher" says "strong", then "student" should say "arm". If the "student" answers incorrectly, the "teacher" will shock the "student". Milgram built a shock box that produced currents of different voltages, ranging from 45V to a maximum of 450V; each time a "student" answered a question incorrectly, the next shock would be raised by 15V—but that's all It's fake, the "students" don't actually get any shocks; the screams are all pre-recorded. (However, in order to convince the real subject "teacher" of the authenticity of the experiment, he himself will receive a 45V electric shock and experience it)

(4) The "student" will answer a few questions correctly as planned, so that the "teacher" will believe No cheating; but then the questions keep getting wrong and the "teacher" keeps applying shocks and increasing the voltage. When the voltage reaches 135V, some "teachers" will hesitate and ask the "experimenter" whether to stop the experiment. After all, the sound from the next room is really miserable. At this time, the most critical test goal of this experiment will emerge: how much influence does authority have on our behavioral decisions?

The "Experimenter" will say 4 sentences in sequence according to the script: ①"Please continue" ②"The experiment needs you to continue" ③"It is very important for you to continue the experiment" ④"You have no choice but to continue"— — We can feel that the tone of these four sentences is constantly improving, and the attitude of the "Experimenter" command is strengthening. If the "teacher" still insists on stopping the experiment after these four sentences, then the experiment will stop; otherwise, the experiment will continue until the voltage reaches 450V.

(5) It is very important for the experimental subjects to maintain randomness. Therefore, the two subjects brought in at the beginning of each experiment had to draw a slip of paper to choose who would be the "teacher" and who would be the "student". However, we know that the "students" actually colluded in advance, so the few pieces of paper drawn by the real subjects all said "teacher". Also, obviously, the experiment has no reference group.

(6) After that, Milgram changed this experiment into 25 different forms, adding different variables, using different subjects (sex, age, race, face to face/across the wall...) The results are similar.

Milgram concluded that although the subjects were hesitant to stop the experiment, the final 65% of the subjects pushed the shock to a maximum of 450V. The experimenter just politely urged the subjects to "please continue the experiment".

Milgram, a Jew, was motivated by this experiment to understand why events like the Holocaust happened. Many German soldiers did not have any deep hatred for Jews, or even hesitated, when they carried out orders from their superiors to kill Jews. But they carried out their orders in the end, as Eichmann did (a clip of the Eichmann trial appears in the film. Milgram's first electric shock experiment was videotaped on May 26/27, 1962, And four days later, Eichmann was executed in Jerusalem), believing they were justified in doing so, because they were just obeying orders. Do they obey their superiors because they are afraid of their superiors' violence? But Milgram's own experimental results show that we ordinary people do not need violence and coercion to obey our superiors, leaders, and authority.

After each experiment, Milgram conducted additional interviews with the subjects (“teacher”). One of the subjects' answers is worth thinking about:

Milgram: (After hearing the screams) Why didn't you stop the experiment at that time?

Subject: Because he (the experimenter) told me to go on

Milgram: Why did you listen to the experimenter but not the one who was suffering?

Subject: Because I feel that this experiment depends on me to continue. And no one told me to stop experimenting.

Milgram: But he (the "student") told you to stop.

Subject: Yes, but he is a subject.

Milgram: Who is responsible for this person (the "student") being electrocuted?

Subject: I don't know.

The subtext of this subject's answer reminded me of a criminological theory: "depersonalization" - the perpetrator will remove the victim's personality and deny his personality in his heart, thereby reducing his sense of guilt when he commits a crime. At the same time, the answer in "Who is responsible" and "I don't know" also demonstrates what Hannah Arendt calls "the evil of banality." This subject did not realize that he was actually the subject after the experiment was over (of course, after the experiment was made public, another question arose).

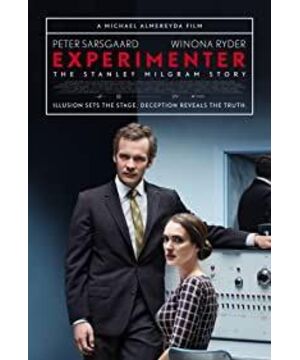

3. Not only is the title of this film called "The Experimenter", but the shooting method is also very "experimental". The whole film has a strong dramatic style. The film's reputation among critics and audiences is quite polar, which is somewhat related to this style of drama.

A. The protagonist of this film, Milgram, often suddenly faces the camera, speaks to the audience, and gives an inner monologue, which is also known as "breaking the fourth wall" - actors on the stage of the drama Read the dialogue towards the audience. The most widespread use of this technique recently is naturally "House of Cards". For a biopic of an academic figure, using "Breaking the Fourth Wall" allows the protagonist to directly expound his theory. After all, there are many academic things that are difficult to show with everyday dialogue.

B. Perhaps what makes some audiences puzzled or even unhappy is that the director has to "indoor scene" or "stage" even some scenes. For some scenes that could have been shot directly, the director deliberately used the curtain as the background. For example, Milgram and his wife Sasha (Winona Ryder) drove to visit Milgram's former teacher, Solomon Asch, another famous social psychologist. That kind of background curtain technology; and at Asch's house, except for the sofa and coffee table for the Asch couple and the Milgram couple, all other furnishings in the home should also be represented by curtains, just like we often watch dramas. as seen.

The director is obviously not short of money - even 5 cents of special effects can't be done like this. I guess the director may be trying to say that for Milgram, life and social environment are like a stage (Goffman's "Drama Theory"). In addition, the black and white backgrounds used in this set of shots visiting Asch may also reflect Milgram's complicated, even tense, relationship with his former mentor, Asch. Milgram was doing experiments and writing reports for Asch in Princeton. He thought that Asch, a famous academic person, would introduce him to some other academic celebrities and help him find a job - no; and Princeton's research institute was heavily bureaucratic, even Ask for a piece of paper, a lollipop, and a report. But after so many years, he still seems to care about what the teacher thinks of him and wants to be appreciated by the teacher.

Solomon Asch has also done some well-known experiments, such as the one to determine the length of line segments. Maybe when you read some books on psychology and conformity behavior, you will mention this experiment; and this experiment also takes conformity behavior as the research object, and also involves deceiving the subjects. What Milgram thought was that if I were to study conformity, it would be more than just a few line segments.

C. Twice in Milgram's monologue in the hallway, an elephant appeared behind him. But no one seemed to notice the elephant—the director apparently used the metaphor of "the elephant in the room": important facts that are well known, but are reluctant to state, or even deliberately ignore. The problem revealed by the electric shock experiment was precisely such an "elephant"; Milgram's subsequent encounters in the academic circle were partly due to his public talk about this "elephant".

4. In the previous electric shock experiment, there was a case of "uncoordinated" in the film: a "teacher" (subject) asked to stop the experiment when the electric shock reached a certain level. Although the "experimenter" repeatedly asked him to continue the experiment, he refused to carry out the request; when the "experimenter" said that you "have no choice", the subject asked back: How could I have no choice? I volunteered to participate in the experiment, and I thought I could contribute something to this research; but if I want to hurt others for it, no, I won't.

The subject with some exceptions was a power engineer, and apparently, as a professional, he was well aware of the consequences when the voltage reached 450V. As a result, he firmly refused the experimenter's request. In connection with the previous question about why ordinary people are willing to obey their superiors and authority (even without violence), if we look at this counter-example alone, we can say: because the world is full of too many unknowns and too many uncertainties for ordinary people , too many risks, and only rely on the knowledge of experts to guide us to make the right decisions, so we obey the authority. I would like to use Habermas's terminology that the "lifeworld" is colonized by "systems".

But did the 35% who refused to obey the "experimenter" command simply because they had relevant knowledge about the shock experiment? And 65% of the subjects who obeyed chose to obey because of their intellectual limitations? When chatting with the French psychologist Moscovici, in order to encourage Milgram to continue such experiments, Moscovici said: Although you have come up with this conclusion, you have not studied why they do it.

(The Frenchman is not identified in the film as Moscovici, but Moscovici is a Romanian Jewish immigrant, experienced the Holocaust, a social psychologist in the 1960s and 1970s, and most importantly, also named Serge. Apparently, that's him)

Ultimately, Milgram had his own explanation, a theory of "the agentic state": individuals are willing to submit to authority because doing so separates responsibility from their own actions; in the In an agentic state, individuals voluntarily turn themselves into tools for others to achieve their goals. People are not without choice, but once he/she chooses the agentic state, it is almost impossible to overcome this identity and resist submission to authority.

5. Although Milgram's electric shock experiment made him equivalent to the electric shock experiment in the public mind, he has also done (or directed) many bizarre sociological experiments; some of which you may have heard of - but didn't know it was Milgram who did it. The director also introduced these experiments into the plot.

A. The Lost Letter Experiment

Milgram made four types of envelopes, each with four recipients, the identities of the four people were: Communist-Party Supporter, Nazi-Party Supporter, Medical Research Association, Mr. Walter Carnap (The name Carnap is clearly a parody of the philosopher Rudolf Carnap) - but they are both in the same mailbox, and the contents of the letter inside the envelope are the same. Then he asked the students to deliberately "lost" these four types of letters in the streets, phone booths, car windshields... As a result, 72% and 71% of the latter two types of letters were sent to the recipient's mailbox, while Only 25% of the first two types of letters are delivered to the mailbox.

Milgram then expanded on the recipients' identities: white political organizations and black political organizations. As a result, in white neighborhoods, more letters from white political organizations were received; in black neighborhoods, it was natural that more letters from black political organizations were received.

B. The Small World Experiment

Perhaps another name for this experiment would be better known - "six degree of separation". In Kansas City and Omaha, Milgram sent some people to help him deliver a batch of letters to a stockbroker named Jacobs in Massachusetts. Of course, these subjects didn't know Jacobs, let alone his full name and specific address; all the subjects had to do was to send the letter to someone he knew and thought he might also know Jacobs to see how many people would pass through in the end. to be delivered to Jacobs. The film gives an example of how an Omaha woman sent a letter to Jacobs through the hands of seven people.

The average result of the experiment is that it only takes 5.5 people to transfer, or even less than 6. Although small-world theory has been around for a long time, Milgram's experiment may be the first empirical test of the theory.

C. People looking up at the sky

If a group of people suddenly stared at the sky on the street, how many pedestrians would follow and stare at the sky? Milgram's research shows that the number of people who actively look up to the sky increases exponentially with the number of people who follow the herd—another experiment on herd behavior. I'm not a sociology student, so I don't know if there are relevant theories or models in the sociology community, but according to some literature I have personally contacted, this kind of phenomenon can be roughly explained by the so-called "information cascade" model in economics. explain.

D. Familiar strangers

When you wait for the bus to work at the bus stop near your home every day, do you think there are a few people who are waiting for the bus like you are familiar? Milgram's research found that you'll probably recognize about four strangers in a scene that you see often but never say hello to.

Among these familiar strangers, there is a category called "socialmetric star" - when you see him/her, not only will you feel familiar, but eventually you will find that you have actually met him/her on other occasions.

(Have you seen "I Love Huckabee"? There is an "existential joke" in it: the hero sees a hotel waiter who he doesn't know in three different places in one day, so he thinks, I must exist with this waiter Destiny connection. According to Milgram's theory, the waiter may just be a "socialmetric star")

6. The electric shock experiment caused many problems for Milgram after it was made public.

The first is that the method of the experiment has been subject to moral criticism from the public and academia. Some people published articles in journals questioning that Milgram's experiments did not conform to experimental ethics; then institutions such as the school's ethics committee were also activated, and some people said that you were manipulating data and fabricating conclusions. The sinister makes everyone very worried." "The purpose of science is to enhance everyone's morality" and so on. There are even people who say, "You force the subjects to torture other subjects in the experiment." This is a typical baseless argument. Milgram tried his best, but it was useless. Later, he couldn't get tenure or funding at Harvard, and he was basically kicked out of academia. Even years later, in TV interviews and on the road, he would meet people who had heard him and would say, "Ah, it's the guy who forced others to conduct experiments with electric shocks," and most of the public had only heard the story, and at most it was After several book reviews, almost no one really got through Milgram's work.

Secondly, the electric shock experiment also cast doubt on Milgram's credibility - because every time he saw him, he suspected that he was also talking about the experiment. There is no way, after all, he really deceived the subjects. After Kennedy was assassinated, Milgram ran into the classroom to tell everyone the news, but the students said they must be doing experiments to deceive us again; another teaching assistant, Paul Hollander, told the students to turn on the radio and listen to the news, but even the radio news was on. , there are still students who suspect that this radio broadcast is also forged by Milgram. It's miserable.

After leaving Cambridge, Massachusetts, Milgram took his family to teach at New York University, where he was able to restore the joy of academic research, published books, appeared on TV talk shows, and even filmed CBS based on him. TV series, gave him a consulting fee. I have the name and the money, but I don’t know why, when I watched the second half of the film, I always felt that Milgram didn’t seem as high-spirited as the first half of the film. Maybe it was because he grew a beard later, maybe because he always felt disliked by the public pointing, maybe he was old and his life was coming to an end, maybe the question of obedience to authority represented behind the electric shock experiment had been bothering him.

(The situation depicted in the film seems to be that Milgram has no friends in academia, with the only exception of Paul Hollander mentioned above; but this Hollander seems to be doing political science stuff later on. Hollander likes to quote gram The words of Kierkegaard, but when he came to visit Milgram in New York, Hollander wanted to quote Kierkegaard, but he couldn’t remember it. Instead, the passing black postman correctly quoted the scriptures for him: “Only backward can understand. Life, but if you want to live well, you have to look forward" - at the beginning of the film, Milgram said this sentence)

7. Winona Ryder plays Milgram's wife Sasha, originally a dancer, and later became a Office worker, meets Milgram in the elevator. In the whole film, Sasha basically does not have any major tension, just the role of an ordinary good wife and mother, but Winona plays a lot of time.

Winona turned 44 in October - time flies, and many of the goddesses of yesteryear are now middle-aged. You can also see blog posts or photos about her from time to time by browsing Weibo - but all of them are fan posts about how he was with Depp or stills and magazine photos when he was young; a few of her recent news or pictures, the following replies are all the same "Old", "beautiful twilight", "killing pig" and so on. This embarrassing situation is all due to the theft (the funny thing is that she stole something from the Marc Jacobs brand, and has since become a good friend of Marc Jacobs). In the past ten years, the small supporting role and the protagonist in the blockbuster are basically independent films and small productions, and they have disappeared from the mainstream vision of the entertainment industry. However, as far as she is concerned, her acting skills have improved a lot in recent years. Although the role of a good wife and a good mother in this film is not great, it is still remarkable; the female politician played in Show Me a Hero this year is even more brilliant. I don't think it's likely that she'll return to her prime, but it's nice to see her grow into a good actress who is becoming more and more sophisticated.

Just write so much.

View more about Experimenter reviews