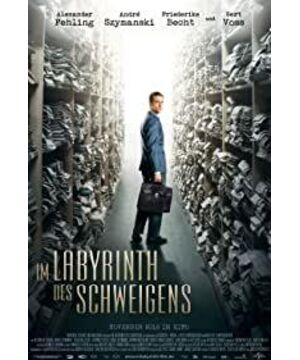

"Auschwitz" has become almost synonymous with Nazi atrocities in World War II in our time. At the mention of it, everyone will remember the chapter on the Holocaust in history textbooks, one of the most "inhuman" chapters in human history. Because of its notoriety known to women and children, it is difficult to imagine that Auschwitz was forgotten in the more than ten years after the war. The Nuremberg Trials in 1945-46 only touched the most important war criminals in the eyes of the Allies, and the Polish authorities in Auschwitz only dealt with dozens of people. A total of seven thousand people. More importantly, these trials were either political performances under Allied control or reckoning by foreign authorities (like Poland), without any ripples in the hearts of the Germans, without exposure, without reflection. The members of the SS who committed evil in Auschwitz quietly hid in the crowd after the war, working as ordinary people and living a peaceful life. It was not until the Frankfurt trial led by Hesse Attorney General and ex-Jewish fugitive Fritz Bauer in the early 1960s that the war criminals of World War II were punished by German law for the first time, and the history of the concentration camps began to torture the souls of Germans. Only then did Auschwitz enter the annals of history, and it became a scar that will forever remain in the memory of Germany and even all mankind. The film "Silence Labyrinth" tells the history of this "scar opening". In Frankfurt in 1958, Auschwitz survivor Simon Kersch (Johannes Kersch) accidentally discovers that the concentration camp guard who tortured him is not only at large, but also teaching at a school. He turned to the state Justice Department for help, aided by journalist Thomas Gunicar, but no one was willing to take on such a thankless case. Out of curiosity, the newly recruited young prosecutor John Radman (Alexander Fehling) took Kersh's lead to investigate. Unexpectedly, the investigation process faced layers of resistance, ranging from the confusion of colleagues in the Ministry of Justice to the lack of cooperation from the police. The executioners of the past are now living a peaceful life. Their materials are quietly piled up in the US military archives center. What people see is the post-war economic take-off and their singing and dancing lives-the indifference to history has built a mysterious labyrinth, turning those who seek the truth. people are trapped in it. Italian-German director Riccia Riley did not make "The Labyrinth of Silence" a biopic of Fritz Bauer, and the Israeli Mossad was just a background. The film is not completely faithful to history. It fictionalizes the slightly romantic character John Ludman, and putting this handsome blond man at the center of the narrative is not only a need for drama, but also a fine-tuning of the perspective of history. . The mainstream narrative generally pays more attention to the historical fact that Bauer cooperated with Mossad to capture the "Nazi executioner" Adolf Eichmann, while the protagonist in the film It is another war criminal "Angel of Death" Joseph Mengele who is being hunted down hard. His medical "research" led by Auschwitz used the bodies of Jewish prisoners as test objects, which can be called the most terrifying in the history of the Holocaust. one page. Ludman was unsuccessful, and he had to focus on other lesser war criminals. The subtitles at the end of the film tell us that Mengele in history has never been punished by the law, but spent the rest of his life in South America and died in an accident. Justice is not always done as we would like it to be, and sin sometimes does go unpunished. In a sense, the historical view of "The Silence Labyrinth" is actually more cruel, realistic and calm. The artistic technique may be romantic and dramatic, but the message conveyed is chilling. Rikia Riley revealed that the greatest significance of the Frankfurt trial was not the reckoning of revenge, but the awakening of the German society that had been intoxicated with post-war prosperity. Every mid-rank SS officer implicated in the investigation is a chilling history, and to make it public is to use a loud, clear, and unquestionable voice to torture the conscience of the Germans and let the entire nation walk out of silence. maze. As a competition film at last year's Toronto Film Festival, "Silence Labyrinth" was released in European countries outside Germany in May this year, undoubtedly marking the 70th anniversary of the surrender of Nazi Germany. This is not a direct reflection on war and massacres, but a reflection on reflection. It shows us that memories of violence and crime are constantly being modified and reshaped, and that the discourse over these memories is also a sinister battlefield, where the enemy's weapons are lies, delay, and concealment. Everyone who strives to find out the truth and retain their memory is a hero in this battle, and the biggest difficulty these heroes face is not cunning war criminals, but our silence and forgetting. It may be a coincidence that an old work by actor Alexander Fehling eight years ago may be the best footnote to "The Labyrinth of Silence": Fehling in "Passenger" plays a contemporary German youth who performs public service in Auschwitz I met a concentration camp survivor. Today's Auschwitz, as the one-sided original text says, is full of tourists after the war, and history seems to have turned a page decisively and never looks back. Fortunately, these literary and artistic works, including movies, also engraved that history in the memory of Germany one by one, and tortured every soul at every reflection. Therefore, history is no longer silent, and we no longer forget. (Published in "Beijing Youth Daily Literary Review" on August 14, 2015, with deletions and changes.) The prisoner's body is an experiment, the most horrific page in the history of the Holocaust. Ludman was unsuccessful, and he had to focus on other lesser war criminals. The subtitles at the end of the film tell us that Mengele in history has never been punished by the law, but spent the rest of his life in South America and died in an accident. Justice is not always done as we would like it to be, and sin sometimes does go unpunished. In a sense, the historical view of "The Silence Labyrinth" is actually more cruel, realistic and calm. The artistic technique may be romantic and dramatic, but the message conveyed is chilling. Rikia Riley revealed that the greatest significance of the Frankfurt trial was not the reckoning of revenge, but the awakening of the German society that had been intoxicated with post-war prosperity. Every mid-rank SS officer implicated in the investigation is a chilling history, and to make it public is to use a loud, clear, and unquestionable voice to torture the conscience of the Germans and let the entire nation walk out of silence. maze. As a competition film at last year's Toronto Film Festival, "Silence Labyrinth" was released in European countries outside Germany in May this year, undoubtedly marking the 70th anniversary of the surrender of Nazi Germany. This is not a direct reflection on war and massacres, but a reflection on reflection. It shows us that memories of violence and crime are constantly being modified and reshaped, and that the discourse over these memories is also a sinister battlefield, where the enemy's weapons are lies, delay, and concealment. Everyone who strives to find out the truth and retain their memory is a hero in this battle, and the biggest difficulty these heroes face is not cunning war criminals, but our silence and forgetting. It may be a coincidence that an old work by actor Alexander Fehling eight years ago may be the best footnote to "The Labyrinth of Silence": Fehling in "Passenger" plays a contemporary German youth who performs public service in Auschwitz I met a concentration camp survivor. Today's Auschwitz, as the one-sided original text says, is full of tourists after the war, and history seems to have turned a page decisively and never looks back. Fortunately, these literary and artistic works, including movies, also engraved that history in the memory of Germany one by one, and tortured every soul at every reflection. Therefore, history is no longer silent, and we no longer forget. (Published in "Beijing Youth Daily Literary Review" on August 14, 2015, with deletions and changes.) The prisoner's body is an experiment, the most horrific page in the history of the Holocaust. Ludman was unsuccessful, and he had to focus on other lesser war criminals. The subtitles at the end of the film tell us that Mengele in history has never been punished by the law, but spent the rest of his life in South America and died in an accident. Justice is not always done as we would like it to be, and sin sometimes does go unpunished. In a sense, the historical view of "The Silence Labyrinth" is actually more cruel, realistic and calm. The artistic technique may be romantic and dramatic, but the message conveyed is chilling. Rikia Riley revealed that the greatest significance of the Frankfurt trial was not the reckoning of revenge, but the awakening of the German society that had been intoxicated with post-war prosperity. Every mid-rank SS officer implicated in the investigation is a chilling history, and to make it public is to use a loud, clear, and unquestionable voice to torture the conscience of the Germans and let the entire nation walk out of silence. maze. As a competition film at last year's Toronto Film Festival, "Silence Labyrinth" was released in European countries outside Germany in May this year, undoubtedly marking the 70th anniversary of the surrender of Nazi Germany. This is not a direct reflection on war and massacres, but a reflection on reflection. It shows us that memories of violence and crime are constantly being modified and reshaped, and that the discourse over these memories is also a sinister battlefield, where the enemy's weapons are lies, delay, and concealment. Everyone who strives to find out the truth and retain their memory is a hero in this battle, and the biggest difficulty these heroes face is not cunning war criminals, but our silence and forgetting. It may be a coincidence that an old work by actor Alexander Fehling eight years ago may be the best footnote to "The Labyrinth of Silence": Fehling in "Passenger" plays a contemporary German youth who performs public service in Auschwitz I met a concentration camp survivor. Today's Auschwitz, as the one-sided original text says, is full of tourists after the war, and history seems to have turned a page decisively and never looks back. Fortunately, these literary and artistic works, including movies, also engraved that history in the memory of Germany one by one, and tortured every soul at every reflection. Therefore, history is no longer silent, and we no longer forget. (Published in "Beijing Youth Daily Literary Review" on August 14, 2015, with deletions and changes.) Live and die by accident. Justice is not always done as we would like it to be, and sin sometimes does go unpunished. In a sense, the historical view of "The Silence Labyrinth" is actually more cruel, realistic and calm. The artistic technique may be romantic and dramatic, but the message conveyed is chilling. Rikia Riley revealed that the greatest significance of the Frankfurt trial was not the reckoning of revenge, but the awakening of the German society that had been intoxicated with post-war prosperity. Every mid-rank SS officer implicated in the investigation is a chilling history, and to make it public is to use a loud, clear, and unquestionable voice to torture the conscience of the Germans and let the entire nation walk out of silence. maze. As a competition film at last year's Toronto Film Festival, "Silence Labyrinth" was released in European countries outside Germany in May this year, undoubtedly marking the 70th anniversary of the surrender of Nazi Germany. This is not a direct reflection on war and massacres, but a reflection on reflection. It shows us that memories of violence and crime are constantly being modified and reshaped, and that the discourse over these memories is also a sinister battlefield, where the enemy's weapons are lies, delay, and concealment. Everyone who strives to find out the truth and retain their memory is a hero in this battle, and the biggest difficulty these heroes face is not cunning war criminals, but our silence and forgetting. It may be a coincidence that an old work by actor Alexander Fehling eight years ago may be the best footnote to "The Labyrinth of Silence": Fehling in "Passenger" plays a contemporary German youth who performs public service in Auschwitz I met a concentration camp survivor. Today's Auschwitz, as the one-sided original text says, is full of tourists after the war, and history seems to have turned a page decisively and never looks back. Fortunately, these literary and artistic works, including movies, also engraved that history in the memory of Germany one by one, and tortured every soul at every reflection. Therefore, history is no longer silent, and we no longer forget. (Published in "Beijing Youth Daily Literary Review" on August 14, 2015, with deletions and changes.) Live and die by accident. Justice is not always done as we would like it to be, and sin sometimes does go unpunished. In a sense, the historical view of "The Silence Labyrinth" is actually more cruel, realistic and calm. The artistic technique may be romantic and dramatic, but the message conveyed is chilling. Rikia Riley revealed that the greatest significance of the Frankfurt trial was not the reckoning of revenge, but the awakening of the German society that had been intoxicated with post-war prosperity. Every mid-rank SS officer implicated in the investigation is a chilling history, and to make it public is to use a loud, clear, and unquestionable voice to torture the conscience of the Germans and let the entire nation walk out of silence. maze. As a competition film at last year's Toronto Film Festival, "Silence Labyrinth" was released in European countries outside Germany in May this year, undoubtedly marking the 70th anniversary of the surrender of Nazi Germany. This is not a direct reflection on war and massacres, but a reflection on reflection. It shows us that memories of violence and crime are constantly being modified and reshaped, and that the discourse over these memories is also a sinister battlefield, where the enemy's weapons are lies, delay, and concealment. Everyone who strives to find out the truth and retain their memory is a hero in this battle, and the biggest difficulty these heroes face is not cunning war criminals, but our silence and forgetting. It may be a coincidence that an old work by actor Alexander Fehling eight years ago may be the best footnote to "The Labyrinth of Silence": Fehling in "Passenger" plays a contemporary German youth who performs public service in Auschwitz I met a concentration camp survivor. Today's Auschwitz, as the one-sided original text says, is full of tourists after the war, and history seems to have turned a page decisively and never looks back. Fortunately, these literary and artistic works, including movies, also engraved that history in the memory of Germany one by one, and tortured every soul at every reflection. Therefore, history is no longer silent, and we no longer forget. (Published in "Beijing Youth Daily Literary Review" on August 14, 2015, with deletions and changes.) The history of shuddering, and making it public is to torture the conscience of the Germans with a loud, clear, and unquestionable voice, and let the entire nation walk out of the labyrinth of silence. As a competition film at last year's Toronto Film Festival, "Silence Labyrinth" was released in European countries outside Germany in May this year, undoubtedly marking the 70th anniversary of the surrender of Nazi Germany. This is not a direct reflection on war and massacres, but a reflection on reflection. It shows us that memories of violence and crime are constantly being modified and reshaped, and that the discourse over these memories is also a sinister battlefield, where the enemy's weapons are lies, delay, and concealment. Everyone who strives to find out the truth and retain their memory is a hero in this battle, and the biggest difficulty these heroes face is not cunning war criminals, but our silence and forgetting. It may be a coincidence that an old work by actor Alexander Fehling eight years ago may be the best footnote to "The Labyrinth of Silence": Fehling in "Passenger" plays a contemporary German youth who performs public service in Auschwitz I met a concentration camp survivor. Today's Auschwitz, as the one-sided original text says, is full of tourists after the war, and history seems to have turned a page decisively and never looks back. Fortunately, these literary and artistic works, including movies, also engraved that history in the memory of Germany one by one, and tortured every soul at every reflection. Therefore, history is no longer silent, and we no longer forget. (Published in "Beijing Youth Daily Literary Review" on August 14, 2015, with deletions and changes.) The history of shuddering, and making it public is to torture the conscience of the Germans with a loud, clear, and unquestionable voice, and let the entire nation walk out of the labyrinth of silence. As a competition film at last year's Toronto Film Festival, "Silence Labyrinth" was released in European countries outside Germany in May this year, undoubtedly marking the 70th anniversary of the surrender of Nazi Germany. This is not a direct reflection on war and massacres, but a reflection on reflection. It shows us that memories of violence and crime are constantly being modified and reshaped, and that the discourse over these memories is also a sinister battlefield, where the enemy's weapons are lies, delay, and concealment. Everyone who strives to find out the truth and retain their memory is a hero in this battle, and the biggest difficulty these heroes face is not cunning war criminals, but our silence and forgetting. It may be a coincidence that an old work by actor Alexander Fehling eight years ago may be the best footnote to "The Labyrinth of Silence": Fehling in "Passenger" plays a contemporary German youth who performs public service in Auschwitz I met a concentration camp survivor. Today's Auschwitz, as the one-sided original text says, is full of tourists after the war, and history seems to have turned a page decisively and never looks back. Fortunately, these literary and artistic works, including movies, also engraved that history in the memory of Germany one by one, and tortured every soul at every reflection. Therefore, history is no longer silent, and we no longer forget. (Published in "Beijing Youth Daily Literary Review" on August 14, 2015, with deletions and changes.) survivor. Today's Auschwitz, as the one-sided original text says, is full of tourists after the war, and history seems to have turned a page decisively and never looks back. Fortunately, these literary and artistic works, including movies, also engraved that history in the memory of Germany one by one, and tortured every soul at every reflection. Therefore, history is no longer silent, and we no longer forget. (Published in "Beijing Youth Daily Literary Review" on August 14, 2015, with deletions and changes.) survivor. Today's Auschwitz, as the one-sided original text says, is full of tourists after the war, and history seems to have turned a page decisively and never looks back. Fortunately, these literary and artistic works, including movies, have also engraved that history in the memory of Germany one by one, and tortured every soul at every reflection. Therefore, history is no longer silent, and we no longer forget. (Published in "Beijing Youth Daily Literary Review" on August 14, 2015, with deletions and changes.)

View more about Labyrinth of Lies reviews