On February 14, 2011, Jeff Goldstein, one of the main collectors of Vivian Maier's works, published an article in the blog section of the team website. The article for "Art, money and Vivian Maier", the content is related to a sensitive topic raised by the "Photographer Vivian Maier" photography exhibition (2011.4.15-6.18) to be held at the Russell Bowman Art Promotion Space. This may be a question that many people care about: Collectors, do you want to make money by discovering, arranging, and displaying Vivian's secret photographs and selling enlarged photos? Jeff gave his own answer.

We recently posted on our website about our upcoming (Vivian) photography exhibition at the Russell Bowman Art Promotion Space and received an interesting letter of comment. This reply comes from street photographer Robert M. Johnson). Bob asks whether we are "chasing profit" with promotions. I think this is a very good question, and it is inseparable from our promotion business. As the saying goes, famous captains are famous for nothing but because they ordered their ships to be scuttled, but I didn't want to do that, so I sent him a long letter back explaining why Now we are going to hold exhibitions and sales of works. At the beginning of the letter, I briefly stated: I am not trying to make money from these activities. The reason for holding the event is that our (photo collection and sorting) business has already made ends meet, and we need this money. income to subsidize. So he also sent me a longer letter, and both Bob and I felt we should share the content of those exchanges.

In my opinion, "art and money" are inseparable, and the source of income is the "lubricant" to ensure the steady progress of the art cause. For a healthy career to grow, artists, art-related activities, and the collecting community need financial income, and galleries and museums are no exception. Donors and collectors provide the lubricant—or financial support—to the entire cause to promote artistic creation and promotion. For artists and promoters, financial support is a necessary backing and beneficial impetus for artistic creation.

The public promotion of Vivian Maier's work is a systematic project. Currently, John Maloof (we are in touch every day) and I do most of the work. Please understand that I'm not complaining, we both have no regrets about our decisions and are deeply proud to be part of this cause. In fact, we've both faced a lot of temptations to pay well, but we've both declined.

You have every reason to ask: what kind of expenses do you have? Although John and I are well aware of each other's financial burden, it is inconvenient for me to directly disclose the pressure on him. Included in the list of costs (in my case): Forming a corporate entity, taking out insurance, attorney fees, accounting fees, fire repairs and temperature controls, dehumidifiers, drainage, alarms and security, employee commissions, Electrical equipment, documentation storage fees, and the cost of acquiring and rescuing Vivian Maier's work.

The last item, the cost of acquiring Vivian Maier's work, is much higher than all the previous projects. Here I would like to mention a collection of Vivian works that John and I just recently purchased, although I can't go into too much detail, we have both been following this collection for a few days. This business is not so easy to talk about. The transaction location is far from Chicago. In a randomly designated hotel conference room, a total of seven people participated, including two retired notary agents to ensure "the transaction is voluntary and fair." Both John and I consider these thousands of photos to be the last of Vivian Maier's masterpieces to stray, and we're delighted to have them successfully brought back to the studio. You should know that John and I have reached an agreement that we will share the collection of works in hand, forming a good mechanism for complementing each other. Of course, due to the complexity of time, economy and initial cooperation, we believe that before embarking on the implementation of the cooperation plan, it is necessary to allow time for both parties until the time is right.

In addition to funding the collection and promotion, both John and I voluntarily gave up our original personal careers. It is difficult to maintain these activities in spare time alone, and it is possible to concentrate when you are not working. I studied art, but was a carpenter by profession (it's a family craft, it's been passed down to me for the fourth generation) and used to specialize in cabinet making. After 30 years in business, I decided to let go of my carpentry work and close my 1,400-square-yard workshop last May. For those who work as dry carpenters, this means there will be no turning back. But I repeat, this is my own choice and decision, no regrets. To support this new venture, John and I had to squeeze money and do whatever it took to move forward. It also put a heavy burden on my family's economy. I didn't have a stable income for eight months in a row, and I had to saw off the sofa because I changed the living room at home to Vivian Maier's work office, just like when I Like having to sacrifice the family restaurant in order to start a carpenter business. But I still have no regrets, and I have spent countless hours filing and editing for this cause. Fortunately, I am an insomniac. So far, I have never received a single cent of financial assistance. In order to continue my career healthily and smoothly, I think it is necessary to obtain some financial subsidies now. There is already a corporate entity in charge of organizing my Vivian work, which is in dire need of funding. So, it's time for an exhibition.

I asked Russell Bowman if he would be interested in putting on a show, since he is well respected by artists and gallerists in Chicago (including me). If you go to the Russell Bowman Art Promotion Space website and click on the "About Us" link, you can see a detailed introduction to Mr. Bowman's profound knowledge. Russell Bowman, who served as director of the Milwaukee Museum for 15 years, will bring you a professional and high-level exhibition hosted by him. Bowman's art space is a small warm and quiet place that has always been my favorite, and it fits the mood of Vivian's work very well.

Also contributing to the show is printing giant Ron Gordon, who has retired but postponed his trip to New York for the show. Ron's protégé, Sandra Steinbrecher, has also assisted him for many years and has extensive knowledge in the scaling of silver salts. I am the luckiest myself. If you want to know more about me, please go to Google to query "Illinois Wesleyan University" and my name "Jeff Goldstein" to find a short article about my artistic career. By the way, I've had a few exhibitions myself in Chicago, one this fall, and a few years ago I've had my own exhibition, but I don't even have a personal website...

As I did with Robert Johnson As said - this article is also thanks to this buddy, in addition to artistic creation, I also love the enjoyment that art brings to me and the intersection with others in creation. I would like to thank all of the people mentioned in this article who are willing to be involved in this cause, it is a great honor to meet them, and it is wonderful to know them. Next, I would also like to thank Paul Natkin, who has given us professional guidance and indelible contributions to our cause. His efforts have also enabled this cause to never deviate from our original intention of paying tribute to the original author, Vivian Maier. for a role model. Thanks also to Anne Zakaras for her passionate work day and night. Next, thanks to Frank Jackowiak and his staff and volunteers for printing and framing Vivian's undeveloped negatives at Dupage College.

I would also like to thank my beloved wife, Lisa Vogel, who does all the computer work, and for her tolerance and understanding: for me and my career, for which she lost a living room.

—Jeff Goldstein

Translator's Note:

Vivian Maier (1926.2.1—2009.4.21), an American street photographer, was born in New York City, but spent most of his youth in France. After returning to China in 1951, Vivian worked as a nanny for a lifetime, and in her spare time is keen on street photography. Her photographic career spanned 50 years and left behind more than 150,000 negatives, most of them in Chicago and the New York City area. Vivian recorded the world around her with great enthusiasm. In addition to photos, she also used home video cameras, tape recorders, and collections of personal items, opening a window for the world to see the American style in the second half of the 20th century. But this may not have been her intention, she never made her work public, and it was purely coincidental that they were discovered and circulated in the world.

In 2005, John Maloof sold his first house and started a real estate business. Since then, he has become more and more involved in community activities in his neighborhood. By digging deep into local local history, he even became president of the local history society on Chicago's North West Side. This area belongs to an often forgotten corner of urban life, and he felt that a book about the characteristics of the place should be compiled to awaken the vitality and charm of the area, so that it will not be looked down upon as usual. So he decided to write a local chronicle called "Portage Park" with others, and this decision would change his life.

The publisher asked them to provide the book with nearly 220 excellent old photos, which must be taken from the life of the neighborhood. In order to find enough images to satisfy this request, John and his collaborator Daniel Pogorzelski had to scour around for old photos. It took them nearly a year, and the two tried their best to find pictures everywhere, even the smallest clues. During this time, John visited a local auction house (RPN sales) to try his luck. Maybe he could get some useful information here. In fact, what he found was a box of negatives taken in Chicago in the 1960s. Unable to confirm the details of the contents, he had to risk nearly $400 for a full box of negatives.

When the two authors studied the negatives, they found that the contents were useless for their own books, so John tucked them away in a cabinet and didn't touch them until the deadline. After a while, he turned out the negatives again and started scanning them. The unpolished real records of the past captured his heart in the photos (he had never been in photography before, and didn't know what the point of these photos was). Gradually, John was infected by the photographer, and he began to record Chicago with his point-and-shoot camera. Photography became his new passion, and he became a photographer.

Let's fast-forward a year, when John's point-and-shoot cameras are a thing of the past, and now he's walking down the street with a Rolleiflex camera, just like Vivian Maier back then. His soul-sucking has exploded, and he is also very interested in the history of photography and those who are photographed. John set up a darkroom in the attic of his home to learn how to develop and enlarge film. At first Maloof was shy about it, but inspired by Vivian's work, he decided to recreate the trajectory of her life and make it his mission.

After nearly a year of hard work, John won 90% of her works from other bidders at various auctions, a total of 100,000 to 150,000 negatives, more than 3,000 photographs, hundreds of rolls (undeveloped) ), as well as film from home camcorders, interview tapes and various other items. Another collector, Jeff Goldstein, has collected 15,000 negatives, 1,000 photographs, 30 rolls of home videotape and some slides, which is roughly the remaining 10 percent of her work.

In 2009, Maloof started a blog and uploaded about 100 of her work, but months passed without a reply. So he went to the HCSP group (Hardcore Street Photography) on Flickr to start a related topic, and the response was very enthusiastic. Since then he has been non-stop in charge of the preservation, research and promotion of Vivian Maier's works.

Thanks to Vivian's seventeen years as a nanny for the Gensburg family in Chicago, John was able to acquire a large collection of Vivian's personal belongings, which had been stored in rented lockers. If he hadn't come to inquire, they would have been sent to the dump. Most of the items in the two cabinets are junk collected by Vivian, such as tattered paint cans, railway spikes or various trinkets, but among these junk are hundreds of rolls of color negatives and precious personal data. These clues took John's research in a new direction. Most of the valuable material is newspaper clippings, which are her treasures. Vivian collects newspaper articles and packs them into plastic folders, then organizes them into volumes and puts them in cartons. Among her relics are hundreds of such clippings. In addition, there is a lot of letterhead, and some of the letterheads sent to her are from various employers. John and his partner Anthony Rydzon researched the information and finally got enough information in the sidebar that they can now roughly frame her life trajectory.

Many families who have employed Vivian will tell you about her strong liberal tendencies, as evidenced by a letterhead in her belongings—that was sent to one of her former employers by the Republican National Committee. Vivian Maier's life experience is reconstructed in these seemingly inconspicuous messages, such as this letter is the only clue to contact her and the Baylaender family. The relics contain numerous shopping receipts, letters (personal or official), notes and other information that will help future generations to study her life. Although she had few acquaintances before her death, we are now able to reach almost every family she worked for. Without her two cabinets of relics, later researchers would have no clues to follow. It was as if she had left us a bunch of puzzle pieces behind her.

Vivian Maier's mother is French and her father is Austrian. She was born in the Bronx, north of New York City. Through investigation of household registration records, Maloof found that Vivian left the United States with her mother at the age of four, accompanied by another Jeanne Bertrand, an accomplished portrait photographer, and her father, Charles, have now faded out of the family's life. Later records show that Vivian had returned to the United States with her mother, Marie Maier, in 1939. When Vivian left France for the second time in 1951 to return to the United States, her mother was not with her.

Vivian started playing with cameras in 1949 when she was still in France, with a humble Kodak Brownie box camera, an amateur camera with only one shutter speed, no ranging and no adjustable aperture. The viewfinder is so small that, in the eyes of a professional landscape or portrait photographer, this extremely unreliable device is likely to ruin Vivian's interest in photography, and the use of such a humble camera is simply throwing cold water on her passion.

In 1951, Vivian Maier returned to New York on the steamboat De-Grass and took a job as a babysitter for a family on Long Island, New York. As a Jewish refugee, she improved her English by watching stage plays. In 1952 she bought a Rolleiflex camera and replaced the shotgun with the cannon. She worked with the family for a long time until she moved to Chicago's North Side in 1956. The Gensburg family in Chicago hired Vivian to care for their three boys, and they became the closest employer family of her life.

When Vivian moved to Chicago in 1956, the Gensburgs lent her a bathroom, which became her private darkroom, where she developed and enlarged black-and-white negatives. Although the economic conditions are not well-off, she went to Canada in 1951 and 1955, South Africa in 1957, returned to Europe and the Middle East in 1959, and came to China in 1956. It is likely that she sold a family farm in Alsace, France, to raise money for the trip, and she also left a lot of photography on the trip.

More than a decade later, the children have grown up, so Vivian ended her first babysitting job in Chicago in the early 1970s. The change of work place made her lose her darkroom, the employers changed from house to house, and the black and white negatives on her hands were piled up and could not be developed. At this time, she decided to switch to color 35mm negative film, mostly using Kodak's Ektachrome, and also replaced the equipment with Leica IIIc cameras, and also used several German SLR cameras including Contax.

These colour photographs are a departure from her previous work and are increasingly abstract. Figures gradually fade from her images, replaced by still lifes, newspapers and graffiti.

In the 1980s, Vivian's creation encountered new difficulties. The financial pressure and the instability of life made her unsustainable again, so the Kodak color rolls could not be washed and piled up. In the late 1990s and into the new millennium, Vivian had to put down her camera and rent two lockers to store her treasures. She moved into a studio apartment with a bathroom all the time, and the rent was paid by the good-natured Gensburg family. And she couldn't even maintain the rent of the locker. In 2007, because Vivian couldn't pay the rent, the locker rental company sold the negatives in the locker to RPN auction house to pay off the debt. RPN then sold them at its own auction, only to be discovered by collectors such as John Maloof.

In 2008, an elderly Vivian slipped on ice in downtown Chicago and injured her head. While doctors judged she would make a smooth recovery, her health deteriorated and she had to move into a nursing home for care. On April 21, 2009, Vivian Maier passed away at the age of 83.

With the efforts of collectors such as John Maloof and Jeff Goldstein, Vivian's works have been on tour in Europe and the United States since 2010, becoming the focus of attention. On November 16, 2011, her first collection of works "Vivian Maier – Street Photographer" was released by Powerhouse Publishing House, and a large number of unprinted negatives left behind are still to be developed and sorted out, and more and more works will follow. appear in the public eye. However, this unique street photographer lives alone, has no children, and even has few acquaintances. In the eyes of the families she has served, Vivian Maier, the nanny, is as respectable as the fairy in "Mary Poppins", and when she takes off her apron and takes her cumbersome camera to the streets, she is a recorder of the city's style. With a click of the shutter, half a century was absorbed into the small negative, and until his death, he never showed it to others. She herself quoted a proverb from Ecclesiastes on a tape: "There is nothing new under the sun."

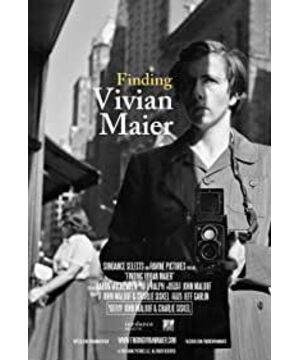

View more about Finding Vivian Maier reviews