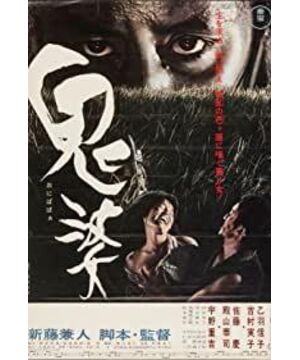

The mysterious history of the Northern and Southern Courts, the romance of the war between the shogun Ashikaga Takauji and emperor Go-Daigo, and the legendary headless king… reenacted with aesthetic beauty and literary interest in Tanizaki's “Yoshino kuzu,” the Sengoku period will find a more realistic and cruel representation in the movie Onibaba (1964). In Onibaba, the camera reveals to us that the capital is burned, ominous events such as a horse giving birth to a goat bodes the ruin of crops, army deserters survive by despicably feigning death and then flee the battlefields, the underclass people resent the war, which takes their men away, destroys their lands, and forever changes their life. In the film, a slightly aged woman lives with her daughter-in-law in a harsh environment,where they eke out a meager existence by killing deserters and selling the soldiers' military equipment. The return of their neighbor, Hachi, poses a threat to the mother. Because Hachi easily seduces her daughter-in-law and without an ally, she can hardly survive on her own. The mother resorts to putting on a demon's mask to intimidate her daughter-in-law into chastity, only to find the mask is cursed and once put on, it can no longer be taken off. Hence, she turns herself into a demon.it can no longer be taken off. Hence, she turns herself into a demon.it can no longer be taken off. Hence, she turns herself into a demon.

If there are key words about films too, Onibaba's are “food” and “sex.” The importance of food to the sustainability of the human race is doubtless. The basic need of eating is accentuated by the hardships of the time. With the conscription of the main labor force of men, women are left behind to a barely livable situation. Morality becomes an unaffordable luxury in such a primitive existence. The two women earn their living by taking lives of those wounded soldiers. They sell the armor stripped from the corpses for rice, and throw the bodies into a deep hole. This scene is immediately evocative of the beginning of Rashōmon (1950), inviting reflections upon the confrontation between the crudest human nature and contrived moral nobility. Similarly,the vignette that captures the two smashing a puppy to the ground and gobbling it by the stove afterwards equally challenges our liberal humanism that celebrates pet culture. Throughout the narrative, the seemingly barbarian women are denied names, and therefore intended to be read as universal. By doing so, the film compels us to reexamine human nature. In circumstances deprived of any material comfort, humans are quick to slide back to animalistic cruelty.

If eating is indispensable to human survival, sexual intercourse is equally important. The female characters, especially the daughter-in-law, can be understood as a symbol of sexual desire. Poorly covered by shabby clothing, the frequent exposure of the two women's bodies suggests an unaffected naturalness. The minimalism of the interior decoration of their dwelling and the black-and-white cinematography further add a primitive touch to their existence. Far removed from community, society, and located in lush reeds, the two widows are liberated from any moral obligation and gender roles. In her naked existential being, the daughter-in-law's sexual drive is insuppressible. Neither the mother's story of Buddhist hell that warns against lust can stop her from throwing herself into the arms of Hachi,nor can the life-risking downpour in the dead of night hold her back from running across the river.

When the mother exhausts both secular ethics and religious admonishment, she puts on a demon's mask as a last resort. Yet the trembling fear aroused by the mask in the daughter-in-law still fail to exercise any restraint in her pursuit of carnal satisfaction. In a tragicomic scene, as the dumbfounded mother stood afar watching the daughter-in-law madly engaging in copulation with Hachi in the rain, all her painstaking efforts are extinguished by the invincibility of libidinal vitality. Yet the mother's obstruction to their union is not so much motivated by anger as it is by fear. In terms of physiological needs, she is just as human as her daughter-in-law is. The first time upon catching a glimpse of the young ones making love, the mother releases her impulse by clinging to a tree, an unmistakable phallic symbol.She has to keep her daughter-in-law from leaving simply because in that case, her own survival would be at stake.

Like the frightening mask that the Atsumori puts on his innocent face, the demon mask that the mother takes from the samurai does not only conceal her fear, but also empowers her at first. However, the mask does not come off from her face like that of Atsumori's, and after it is taken off by force, her original face becomes so severely disfigured that it transforms her into a literal monster. The narrative's execution of its poetic justice is thought-provoking. The mother is no more sinful than any other characters , who invariably and involuntarily slaughter humans, nor is she less self-centered than others, as moral enlightenment is simply not the interest of the story. The fact that the mother is chosen to suffer the misadventure seems to suggest that after all, demons are not gruesome by nature. On the contrary,demons might be the most pitiful and objective creatures inside. The men/mask/face they wear constitutes the imprisonment of themselves and at the same time demands fear and repulsion from others.

View more about Onibaba reviews