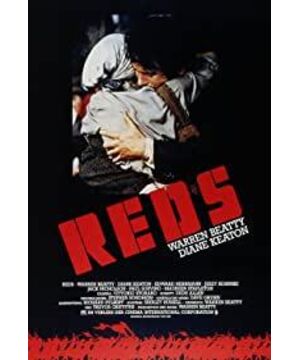

Reds (1981) is a 194-minute film that I finished in one sitting. Indeed, Reds has compelling material: whether it's stories about minorities (John Reed, the American left-wing journalist and author of "Ten Days That Shaked the World"; the heroine, Louise Bryant, an American feminist writer. Other characters include The Nobel Prize winner for literature, the American dramatist Eugene O'Neill, the anarchist Emma Goldman, etc.) or the background of the great era (the Soviet-Russian October Revolution), it is easy to play. Moreover, director Warren Beatty focused the narrative on the theme of faith and love, which is suitable for all ages. However, when you think about it, the connection between revolution and love, in addition to the consideration of the box office, is indeed comparable. As John Reed argued to Zinoviev, Chairman of the Executive Committee of the Comintern, his love for the revolution did not mean giving up his love for his wife, and sincere love made the passion of the revolution purer. Freud's "pansexualism" seems to be the best footnote for this, but I prefer to point out that it is based on self-authenticity: revolution is not self-alienation in posturing, not an instrument of social exchange, Rather, it is the individual's conscious and spontaneous radical transcendence - transcending one's self or some kind of embarrassing living condition of human beings. In this sense, the real revolutionaries could only be fringe people like John Reed, not the powerful Zinovievs. There are too many issues for Zinoviev to consider, and his words and deeds may turn into political events at any time, so the instrumentality must always prevail over the authenticity, and the revolution will become more and more distant from the body. John Reed, on the other hand, had nothing and could not have anything but his faith in love and revolution—the impulses that pointed to his innermost being. So the flames of revolution and love became more and more fiery in his body, until the last bit of strength of his life was exhausted. The second commonality of revolution and love—even if they are truly self-authentic—is that they are often doomed to disillusionment. As Arendt pointed out in On Revolution, "The October Revolution has the same profound significance for this century as the French Revolution has for its contemporaries, first turning mankind's best hopes into reality, and then making them utter despair" (p.45). The seemingly legendary love between John Reed and Louise Bryant, the revolution of the two of them, is actually the same. So when Eugene O'Neill pointed out to Louise, who was alone in the empty room, John should not treat you like this, he should always keep you in the center of focus. Louise, a woman who loved herself so much, naturally collapsed into a mess. Fortunately, in Warren Beatty's script, the later big times saved them: the big times made Louise look at John's face with so many people in the majestic international singing, and burst into tears with excitement; Louise was finally able to accompany John through the last moments of his life. However, not everyone's revolution/love can meet such salvation, or, in other words, the salvation of the great age reflects only deep despair ("Liberation and freedom are not the same thing; liberation may be the condition of freedom, But by no means does it automatically bring freedom; the idea of freedom contained in emancipation can only be negative". See Arendt, "On Revolution," p.18). The essence of the disillusionment of revolution and love is this: Revolution/love is not a panacea, but people want to use it to solve all problems - whether it is an unbalanced social structure or interpersonal structure, anomie social order or psychological order - it works day and night, once and for all . Here again, we seem to be confronted with the problems of that era, namely, our ingrained linear view of time, our belief in self-realization in this world, and the unprecedented existential anxiety it brings. The last thing that revolution and love have in common I want to talk about is that "all stories that are created and acted by men . On the Revolution, p. 52). In my opinion, John and Louise probably never realized that their love would be tied to, and ultimately part of, such a big time. They just follow their inner impulses and walk in response to the unknown life. They just go down in twists and turns, stumble, ups and downs. Who knows that accidentally, looking back, it has become a piece of history! However, such a history and such a meaning cannot belong to them in love. It can only exist in Louise's cry at the passing of John, only in her old memories (if any), and in people's conversations years later. In any case, people in a revolution/love do not know the true meaning of their actions, and once the meaning (if possible) is recognized, whether it is desirable or not, the revolution/love is over. In this way, as embodied in Revolution/Love, people's lifelong pursuit of meaning - a process of de-absurdization fueled by absurd anxiety about existence - tends to make their own existence even more absurd: What you want is always lost in the moment of grasping; to keep grasping is to keep losing.

View more about Reds reviews