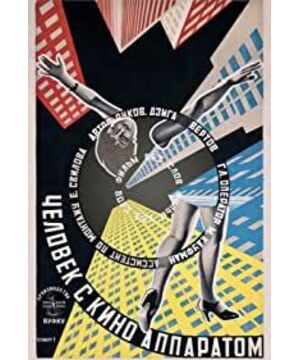

The audience is seated, the film is about to be shown, and what is being shown is the main part of "The Man with the Camera": an unprecedented visual journey, we will follow the lens through a city, day and night, capturing every aspect of urban production and reproduction. throb and weave them into a brilliant urban symphony. And we also realized that it was the invention of the camera that made this visual travel possible.

"The Man with the Camera" marks a momentous moment when the city we inhabit suddenly comes to life, and this life for itself is presented to us through a series of extremely avant-garde cinematic techniques: elevating photography, downgrading Photography, double exposure, quick montage and more. Unlike his Hollywood colleagues across the ocean, Djiga Vertov doesn't see these newly invented stunts as bewildering tricks; for the cinematic revolutionary, all of them are necessary to characterize the city. All of this heralded the birth of the "kino-eye," as he put it in his ebullient essay on visual revolution. However, contrary to common understanding, the "movie eye" is not a one-way derivation of the human eye; it is a bridging of the flesh and machinery, a hybrid of the naked eye and industrial vision. Only in the "cine eye" and even in the emerging medium of film did Vertov find the dialectical balance between machinery and labor.

Decades later, pioneering director David Cronenberg repeated/inverted this dialectic in films such as Murder on Videotape. The mechanical or mechanical eroticization that proliferates from the human body has become the most gruesome imagery in the history of postmodern cinema, and related to this is the post-industrial dungeon that Cronenberg is fascinated by. These lustful, gloomy and icy cities are clearly different from the ideal capital Vertov constructed in "The Man with the Camera": a combination of Moscow, Odessa and Kip, transformed through complex montage techniques into A socialist industrial city.

However, just like Cronenberg, Vertov places the production of the body—the production of the city—the production of visual images on the same plane. In the urban production life of this day, the tools and structures of different production fields are poetically connected together by means of montage: for example, train wheels, textile wheels and film rollers, transportation, subsistence production and video production are all in A similar mode of operation is presented in "Cinema Eye" and the possibility of a universal mode of production is emphasized.

If the standard Marxist reading of Cronenberg's films is that the bourgeois individual encounters the ultimate alienation in the age of media and obtains the only possibility of redemption by relinquishing his own subjectivity, then "With a Camera" "The People" is just the antithesis of Marxism: large-scale industrial production does not necessarily produce alienation and materialization, and new abstract forms can be extracted between different production fields and different types of work. "The Man with the Camera" has a visual dialogue with "The German Ideology". In the latter, the textile industry has become the epitome of the entire history of material production, while in the former, the rollers and axles in the textile industry have become the starting point of video dynamics, from industrial workshops to modern film industry, from clothing production From the production of visual landscapes, each production category is historically linked, and the modern city is subtly conceived with its imagery similarities.

Thus, Marx's labor theory of value was developed into a montage theory. By rationalizing, streamlining, and standardizing industrial activity in all sectors of society (oddly, contrary to what later cultural critics imagined, what this repetitive mechanical movement implies is not exploitation and the barrenness of everyday life, but an inexplicable poetic), montage transcends the meaning of film technology itself and becomes a state of modern life: it is both fragments and organically connected fragments; it is both the essence of modern life and the modern Social and film narrative systems produce meaning.

When an ideal and rational modern urban life is realized in "The Man with the Camera", what we can't forget is that all this is possible only under the care of the "movie eye"; we can't ignore that As if it was a superfluous opening: For Vertov's "The Cavemen," cinema was never a phantom of entertainment, but a way of educating and enlightening socialist citizens. When Vertov said that the "cine eye" is "a form of image recording that deconstructs not only the world that the naked eye can see, but also the world that cannot be seen", we can always learn from his contemporary Benjamin The response was found there: "Our hotels and city streets, our offices and living rooms, our train stations and factories, all seemed to imprison us hopelessly. Then came the movie, and it was a tenth The prison was blown to smithereens in a second, with the power of a bomb, and now, at last, we can swim freely among the ruins. Close-up expands space; slow-motion prolongs time. As the camera goes up High and low, cinema intervenes in our lives... It takes us into an unconscious visual world, just as psychoanalysis leads us into an unconscious world of desires." Thus, in Vertov's imagined city-state, the film He came as a redeemer, the surface of society was penetrated by light beams, and the concealed social relations became clearer in the obscurity; when citizens from all walks of life and fields gathered in the cinema, the moment of enlightenment came.

View more about Man with a Movie Camera reviews