[From "Film Noir" Chapter 4 Low is High: Budgets and Critical Orientation]

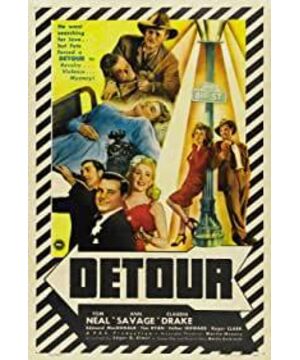

Ulmer is a true low-class aesthete, and he seems to enjoy mixing subtle esoteric with vulgarity. In fact, he was one of the most talented European directors who immigrated to the United States in the 1920s and 1930s. When he was still in Germany, he was not only a scenographer for Max Reinhardt, assistant to FW Murnau, Lang and Ernst Lubitsch, but also a collaboration with Robert Theodmark (Robert Theodmarkt). Siodmak, who co-directed Menschen am Sontag (1930), not only that, but he was also a self-proclaimed "artistically fascinated" intellectual, a sympathizer of Bertolt Brecht and the The Bauhaus has a sense of intimacy. In America, however, he devoted most of his time to Yiddish art films, cheap Westerns, instructional films for the Ford Motor Company, and films like Girls in Chains (1943) exploitation movies. He told Peter Bogdanovic: "I know Mayer and I'm proud he would never have hired me!" At the peak of his directorial career, he was dubbed "the Capra of the PRC", which It means that he has his own creative team and can get relative creative freedom in a small production company. His masterpiece, Detour (1945), was a truly cheap film, shot in just six days, with a ratio of 2 to 1, only seven dialogues, and just over an hour long. From what I can find, the only review for the film in the U.S. is from Variety, which calls it a "good addition movie" (January 23, 1946). However, it was in the same era as, and no less than, the first Hollywood films, which the French called film noir.

Martin Goldsmith wrote the script for "Detour," in which more than just James Caan's shadow can be seen (after the success of "Double Indemnity", Ulmer wrote "Single Indemnity" for PRC immediately) ( Single Indemnity ), and draws on the fatalistic and slightly crazy novels of Cornell Woolridge and Frederic Brown, as well as the ups and downs that were popular on radio in the 1940s. weird story. In keeping with these inspirational sources, the film's mise-en-scène distills the best of hardcore stereotypes. At the beginning of the film, Al Roberts (Tom Neill), the protagonist of the film, is dressed in rumpled clothes and a short-brimmed hat, drinking in a small roadside restaurant outside Reno. with coffee. When a truck driver drops a coin into the jukebox, Roberts' voice-over asks, "Why is it always this corny song?" The film thus enters a routine flashback, a story about desire and Strange tale of death.

Like Walter Neff in "Double Indemnity," Al chalked up his problems to a trick of horns. Flashbacks show his good old days, when he was still playing the piano in a New York nightclub where his girlfriend Sue [Claudia Drake] was the star singer. Al seems to be gifted, but when Su travels to Los Angeles to pursue her stardom, he sinks. In one scene, he received a pitiful tip for soloing Brahms in a violent, boogie-woogie style. Soon after, he quit his job and hitchhiked west. However, throughout the journey, he never knew where he was going. On the highway, he hitches a ride with Charles Haskell (Edmund Mac Donald), who shows him a scar from a teenage fight And a nasty scratch he said was from an angry woman not long ago. That night, while Al was driving, Haskell fell asleep in the passenger seat and died mysteriously. Fearing that the police would mistake him for a killer, Al buried the body and replaced Charles Haskell. When he crossed the border to California, he gave a ride to a flirty woman named Vera (Ann Savage), who later confessed that she was the one who scratched. Woman with Skell hands. Vera mocks that Haskell's death could have been an accident, and threatens to report Al unless he sells the car for half of her money. After arriving in Los Angeles, Vera accidentally discovers that Haskell is the heir to the estate of a dying millionaire, so she asks Al to continue playing his role. They spend the night drinking in the rented house, arguing over her plan to get the inheritance. When Al refused to proceed, she grabbed the phone, ran into the bedroom, locked the door, and threatened to call the police. Al grabbed the long telephone line and pulled it hard, trying to break it, but when he broke down the door, he found that the line was already wrapped around Vera's neck. As he stands next to the body, a superposition takes us back to the small restaurant outside Reno, where the story begins.

Because of its production model, Detour is outdated in many ways. Leo Erdoty's rich soundtrack, crude set-up and occasional technical shortcomings all reinforce that feeling, but Ulmer isn't Ed Wood. Only one example of his artistic skill needs to be seen, the diner scene at the beginning of the film, where there is a clever optical illusion. Medium shot of Tom Neal across the bar with a glass to his right while "I Can't Believe That You're in Love with Me" on the record player coffee. The camera moves forward, the medium shot becomes a close-up of Neil's face, and the lights suddenly dim, indicating entry into the character's subjective mood. Spotlights hover around his eyes, making him look like a devil, and for a split second, we sense the presence of a technician behind the camera, busy getting the lights right. Neil bows his head in contemplation, and the camera shoots down his coffee mug; however, this is no longer the original coffee mug, but a model several times larger than the original, which is in front of him in an almost surreal way Impressively. (See Figure 25 to Figure 27)

Few people will realize that the coffee cups are replaced in this scene; in fact, Ulmer doesn't want the audience to notice this, and he uses these seemingly ordinary props to create dreamy close-ups for later nightmares Like a flashback to pave the way. In this and other respects, he resembles Alfred Hitchcock, who once ordered technicians to create a giant pair of women's glasses while filming an important scene in "Stranger on a Train." Not surprisingly, both directors were trained in the German film industry at a time when all scenes had to be determined through the camera's viewfinder. Ulmer was the set designer for Murnau's Sunrise, one of the most subtly restrained films in film history, and Detour has a lot in common, for example, its studio expressionist approach , its focus on camera movement and off-screen space, and its intense subjective narrative.

Ulmer lacks the rich technical support of Hitchcock and Murnau, but the relatively low cost gives him an advantage instead. Detour is so low on the economic and cultural scale that it escapes commodification, and it can even be considered a subversive or avant-garde art. It's a strong work, almost all scenes shot indoors, and it overcomes strict budget constraints through process screens, minimally decorated sets and expressionist designs. Ulmer applies breathless minimalism to his scenes: New York is just a foggy soundstage and a streetlight, Los Angeles is just a used-car parking lot and a drive-in restaurant. At the same time, he also used old-fashioned visual techniques quite effectively, such as swipe-in-out and circle-in-circle-out, and he was, perhaps, the only one of this period—besides Orson Welles—who consciously used back-projection compositing The artificiality of Hollywood directors. Note the scene in which Al drives while Haskell falls asleep: behind Al, the white fences or fence posts on either side of the road are greatly enlarged and flash past in dizzying blur.

"Detour" uses almost all of the modernist themes and motifs I mentioned in Chapter 2. Not surprisingly, the film's narrative style reminds contemporary film critic Andrew Britton of Henry James' novel and Freud's essay on secondary corrections. To me, Britton seems to be overemphasizing the hero's sense of sin, but I agree with him that Al Roberts is an unreliable narrator who travels through an American wasteland. The last topic is especially important. Like many open road noirs, "Bypass" depicts America's western frontier as a desert wasteland, and the characters' quest for personal freedom ends up being nothing but meaningless reincarnations or traps. It foreshadowed Hitchcock's "Psychopath" almost fifteen years in advance: a barren land seen through a car window; a protagonist who drives day and night, staring in the rearview mirror every now and then, listening to the voice of a villainous highway cop in sunglasses; a used car deal; a cheap and deadly motel room.

Here, the low cost once again helped Ulmer. "Detour" doesn't need to indulge in the desperation of a Hollywood designer's head, because its own cost-cutting creates an atmosphere of austerity and claustrophobia. This dilapidated set design reinforces the film's themes of social and cultural impoverishment, and the actors in the film seem as marginal as their characters. Everyone in the film is a lowly supplicant or impostor (even Haskell is a "hymn salesman"), and no one has a chance of success.

The most disturbing supplicant in the film is Vera, compared to the femme fatale in the noir films of the same period. Like Al, she hitchhiked across America and, by her own account, when Haskell picked her up outside of Shreveport, she fought off his inappropriate desire to let him A man faces an infected hand from scratches. In a way, she's Al's double, but when she wakes up from a brief nap in the passenger seat, she also looks like Haskell's ghost reincarnated for revenge this world. Al didn't know what to do with Navila. "She looked like she had just been thrown out of the dirtiest van in the world," he said. However, he was aware of her "beauty", "ordinary, but real". In fact, she has dark circles under her eyes and coughs like a tuberculosis ("Hitchhiking is not a way to protect your schoolgirl's face," she says). Al compares her to Camille, but apparently she's not one of the haggard, self-sacrificing heroines of sentimental melodrama; instead, she taps into the pain of greed and frenzied exploitation at the heart of the film nerve. Cruel and frantic, she paced around her Los Angeles hotel room in her bathrobe, pouring her own whiskey, smoking cigarette after cigarette, and conspiring to make ill-gotten gains. She probably knew she was dying, but she settled Al easily, scolding him first, then inviting him to bed. This gloomy, dangerous yet sympathetic character is bound to leave an indelible impression on audiences, and it's hard to imagine her being allowed in an A-movie. As Al sat in a diner outside of Reno recalling her face, all he saw was nothing but void.

On many levels, "Detour" supports the idea that low-market thrillers are more realistic than typical Hollywood productions, less hampered by bourgeois-liberal sentimentality or totalitarian spectacle. Unfortunately, however, few of the most acclaimed films of this kind are so disturbing, and none were made on such a low budget. Poor's Lane's production model was condemned to death in 1948, when the big studios were ordered to disassociate themselves from theaters; the appreciation for so-called B-noir films came much later, and when critics used the When it comes to terms, they are referring not so much to actual costs as to a misunderstanding of cheapness—a unique blend of immature theatrical style, artistic sophistication, and subversive meaning.

View more about Detour reviews