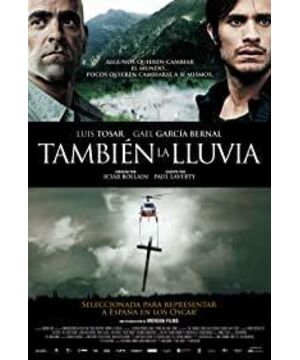

Speaking of Spanish movies, the first reaction in my mind is Pedro Almodóvar's works about love and love and a large number of "thriller and suspense films". Especially the latter, I don’t know if it’s accidental or not, many Spanish directors have all ordered the skill tree of this type of film, which makes Spanish-made thriller and suspense films not only of high quality, but also of a large number and a wide range of categories. However, the film "Rain Crisis" has refreshed my understanding of Spanish films, and I can make excellent works under realistic and serious themes, especially for Isiah, a female director who is known for her feminist themes. As far as Bolayin is concerned, this work with self-deprecation and reflection shows considerable ambition.

The most visible manifestation of this ambition is in the narrative. The director divides the film into multiple levels. The main line of the story is that a crew from Spain came to Cochabamba in Bolivia to shoot a film about the time when Columbus led a fleet to land in South America and carried out bloody killings against the local Indian tribes. Conquer movie. During the filming of the film, it coincided with a large-scale conflict between the people and the government over drinking water in Cochabamba, and the relevant personnel of the crew were also involved in the incident. The film made by the crew is set as a structure within a play, so it is too intertwined with the present, fiction and fact in the same time and space, making the content of the film very full.

At these two levels, we can find that the brutal exploitation of the native Indians by Western civilization has never changed. In the play, the colonists headed by Columbus imposed brutal and inhumane rule on the aborigines, forcing them to pan for gold, and massacred them if they failed to meet the standards or had disobedience. In the main line of time and space, the water company from the United Kingdom monopolized the water resources of Cochabamba, resulting in a 300% increase in water prices. The local poor (mainly Indians) could not afford water and could not bear it. The only way to fight is to resort to violence.

A supplementary statement must be inserted here, that the "war on water" in Cochabamba is real. Some people may find it strange that the country can still make the common people unable to drink water? García Márquez, author of "One Hundred Years of Solitude" once said: "What seems magical, for us is an everyday reality." In Latin America, the land of magical realism, everything is It could happen. That was true in Marquez's time, and it is the same now.

Around the end of the twentieth century, Latin American countries began a wave of economic privatization. But this sudden shift has brought a number of unbelievably bad changes to Latin America. One of the most iconic events is the privatization of water resources. In those crazy times, rivers and lakes could be used for mortgage guarantees, and they could also be used for auctions to change hands. Even water services for urban residents could become privately traded commodities (the specific reasons will be analyzed later). Bolivia is a typical example. In 1997, the government brought in two multinational companies to conduct pilot projects in two cities in the country (one of which is Cochabamba in the film), and the result was not only limited water supply, but also extremely high water prices, which the poor could not drink at all. to clean water. In 2000, the people of Cochabamba successfully ended the bad government of local water privatization through a large-scale protest movement.

Returning to the film itself, the key figure in bridging history and reality in time and space is Daniel, an extra local recruited by the crew. At the beginning of the film, Daniel appears as a somewhat "thorny" interviewer. The producer Costa thinks Daniel will cause trouble, but the young director Sebastian thinks that this person has a personality and is suitable for playing the role of the year. The Taino chiefs encountered by Columbus. Unexpectedly, although the filming went smoothly, Daniel participated in the struggle of local residents against multinational companies, and was even a stalwart. As Costa anticipated, the filming was delayed due to Daniel's arrest, and as the protests worsened, the safety of the crew was affected.

It can be said that Daniel is a very symbolic character. In the play within the play, he played the Indian leader who resisted the colonial rule, and in reality he took on the role of the banner of the protests. The cruel history repeats itself again and again. As for the crew, they represented a part of Western bystanders, some of whom were "hypocritical", such as an actor who played the role of Father Casas who sympathized with the Indians in the play (a real historical figure who once called for an end to the torture and killing of Indians, strict Condemning Spain's crimes in Latin America), although the character in the play is so righteous and strict, but in reality, when he saw the demonstrations caused by the inhuman treatment of the local people, he immediately wisely defended himself, and was the first to propose to leave Bolivia.

Another representative figure is the producer Costa. At first, he saw hiring locals as a means of saving money (only $2 per person per day), but in fact it was another kind of exploitation. However, after a period of conflict and reconciliation with Daniel, his thinking has fundamentally changed. The most direct manifestation is that when Daniel's wife begged him to help his daughter who was injured in the demonstration and to find her husband, Costa finally gave a helping hand regardless of the danger, which was also respected by the Daniel family. and grateful. In an earlier episode, Costa had asked Daniel why he would rather give up the opportunity to make money (he promised Daniel a big payout if he kept his feet on the set for three weeks) to go to a demonstration? Daniel replied: "Water is our life, you won't understand." At the end of the film, Daniel gave Costa a small bottle of water as a gift, echoing his answer at the time.

But, as a bystander from Western civilization, does Costa really understand the meaning? Or, there is also a sense of helplessness.

Finally, let's take a look at why events like "water wars" are still frequently staged in the Latin American world today. First of all, in the final analysis, one word is "poor", and poverty is the original sin. The country wants to develop (including improving water conservancy facilities), but has no money, and caught up with the Latin American economic crisis in the 1990s, so it can only ask the World Bank to borrow. The second is "naive". The Latin American government and academia mistakenly believe that placing a clear price on water resources and transferring them to large foreign companies with higher technical levels and more advanced management can promote water resources investment and development and reduce the cost of water resources due to lack of technology. waste caused. They firmly believe that private companies entering the public service can avoid corruption and operate more efficiently. In order to raise money and solve the drinking water problem, let whoever has the money do it.

And those multinational water companies have seized this opportunity, promising to help these countries get more international loans and debt relief, and at the same time using their influence in the international financial community to coerce the governments of Latin American countries to release their water supply. resource markets, or cut off their borrowing channels. Through all kinds of soft and hard coercion and coercion, a large number of Latin American water rights have been controlled by these large enterprises. By 2002, 48.9 percent of Latin America's water supply was controlled by private capital. But what Latin Americans did not expect is that multinational water companies often appear harmless to humans and animals when they first enter the market. After they occupy a monopoly position, they will start harvesting. After all, capital is profit-seeking. In order to save costs and make high profits, they not only increase water prices, but also allow a large amount of untreated sewage to seep into underground aquifers, causing permanent pollution.

To make matters worse, these exorbitant water bills don't end up going to the water network, but instead are being used to invest in private water companies' overseas expansion plans, as well as generous dividends and executive compensation. Subsidiaries of six multinational companies that monopolize water affairs in Latin America collude with each other and use the money from Latin America and other regions to divide up the global market. In the face of all kinds of criticism, the public relations method of multinational companies is very simple and crude, that is, to continue to maintain a monopoly position by bribing local officials. It was not until later that the new leftists in Latin American countries came to power one after another, expressing their opposition to neoliberalism, reducing social injustice, and especially ending the monopoly of water rights by multinational corporations and taking back water rights. This absurd farce of water privatization finally came to an end.

Sadly, although hundreds of years have passed since the colonialism of Western civilization on Latin America starting with Columbus' landing, the wandering spirit of Western centrism is still lingering over Latin American countries, which is the root cause of Latin America's predicament. Perhaps, from the day the Daniels' ancestors began to speak Spanish, this predicament will be with them forever.

♑

View more about Even the Rain reviews