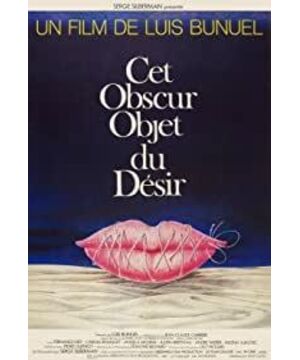

{March 31, 1978} By Dave Kehr from When Movies Mattered_ Reviews from a Transformative Decade

Luis Buñuel, who will turn 78 this year, is still a radical when it comes to surrealist cinema. It's been half a century since he opened an actress's eyeball in "An Andalusian Dog." The film, directed by Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali, shook the whole of fashionable Paris. Audiences today may not be as easily shocked as they were then. For Buñuel, directly offending his audience is no longer as fun as it once was. But his films are still sharp and aggressive, violating our little complacency, our assumptions, our flimsy fantasies—the ones we have to rely on to make our lives seem orderly, It is understandable, at least something worth living.

After 50 years in film, Buñuel no longer needs the pompous skills of his earlier films. In "Hazy Desire," dead donkeys and bound priests are gone, replaced by death, religion, and more than superficial themes of bondage. These themes transcend their symbolism. Buñuel made the imagery simpler, less creepy and more insidious. Throughout "Hazy Desires" is a scene that Buñuel cuts repeatedly to "the train galloping past the countryside." At first, the meaning and role of this image in the whole story is easy to explain: Mathieu, a wealthy old gentleman (Fernando Ray), is serving him in the first class of the "Serbia-Madrid" express. His traveling companions recount their strange affair with his maid, Conchita. What could be more natural and traditional than segmenting an entire story through a "movement train" flashback? But the audience knew something that even Mathieu himself didn't know: Conchita was on the same train at this time. The woman Mathieu thought he was fleeing was actually standing a few yards behind him in hysterical fury. The train was moving, but it wasn't taking Mathieu anywhere. There are other associations in this image, the discreet glamour of the bourgeoisie (1972), the seemingly never-ending walk in the countryside of the dinner-party guests in The Phantom of Liberty (1974). Uninterrupted journeys, the pilgrimage routes described in The Galaxy (1968), and even earlier examples in time and evolution, such as those in Robinson Crusoe (1952) Buzzing insects. It is worth noting how the images that represent meaningless movement and dislocated energies have been refined from the far-fetched insect "symbols" to the understated "train" shots? One of the hallmarks of being a great film artist, in my opinion, is the ability to be parsimonious and condensed, to get resonance from the simplest of images, without wasting a single frame, and to make them meaningful on multiple levels.

The train carries a strong hint of a fertility cult, a Freudian cliché. "Hazy Desires" is a film about unfinished business - Conchita constantly bothers Mathieu with excuses that range from the vague to the downright unreasonable. So the train itself echoes Mathieu's frustrated lust—it never made it through the tunnel. But at the same time, Buñuel also used those clichés to take advantage of this by placing a psychology professor among Mathieu's companions (which, in his own words, could offer "private lessons"). to mock them. Played by a four-foot-tall dwarf, the professor fiddles with his beard in a perfect "German male professor" gesture, and delivers something surprisingly shallow in Mathieu's narration. The startling "observation" - also Buñuel's little warning to those trying to interpret the film in a psychoanalytically flippant way.

Buñuel is a poet of contradictions. On the opposite side of Freudianism, Buñuel makes use of Freudian imagery, but that is only superficial. His most basic narrative tactic is to establish contradictions: a character who represents one attitude in one scene and the exact opposite in the next. While much of the film is still devoted to creating coherent, convincing characters, Buñuel delights in abrupt transitions and unexplained changes. In "Hazy Desire," he went so far that he chose to play Conchita with two actresses, and had a third voice the role. As the guardian of Mathieu's hazy desires, Conchita neither lives up to the standard of a traditional film character, but has long surpassed that standard. Beneath the dual nature - the ruthless, slightly shrewd schoolgirl played by the French actor Carole Bouquet, and the Spanish actor Ann Angela Molina's gentle, maturely charismatic woman, Conchita, has a more complex reality than the characters we've seen in fictional films in the past. In movies, we tend to understand a character by appearance. This is Eisenstein's concept of a "typage": a character is what he sees. But Buñuel breaks this convenient lie, he gives Conchita two faces, two personalities, and mixes them up as the film goes on, which explains why Conchita 1 No. can act like Conchita 2 and vice versa. The saint/slut dichotomy doesn't exist in the movies: Conchita is never so thoroughly open and "explained" that we perceive her as a human being, not just A shadow on the screen - she's always been a mystery, with something unpenetrable and unattainable about her. Still, as Conchita is stripped of the attributes of reality that belong to the actress herself, she unknowingly becomes a generalization: not just a woman, but some kind of eternal source of eroticism. She is the object of love, the reward that wild romantic passions will always seek and never lose. At first, when Conchita rejected Mathieu's courtship, he was angry and frustrated. But as he kept coming back to her, pleading, it became clear (if not for the character, but for the audience): that frustration is fulfillment, because the desire for want is more satisfying than fulfillment itself satisfy. Even when rejected, shunned, and humiliated, he kept returning. Fullness is a state of anti-climax - Mathieu experiences true ecstasy in the midst of his own anger and pain. He and Conchita are the perfect couple. The name Conchita, the movie tells us, is short for "Concept" in Spanish, and the movie gives Conchita the perfect revenge. Here, Buñuel almost blatantly declares the religious theme that has always hovered over his work. Mathieu, a priest in a sense, worships the shrine of the Virgin Mary and prays for a return that never comes. For Buñuel, the biggest lie of the Catholic Church is to give hope and turn hope itself into a reward for it. If our actions are always frustrated, if our desires are never satisfied, what do we get from the world but hope? Buñuel made Mathieu an extremely wealthy man - making everything within his grasp. But Conchita told him that what he really wanted was exactly what he could never get. And that's what made his life possible and made him happy. Like many of Buñuel's films, Hazy Desire is built on repetition and breaking, predictable and unpredictable rhythm. The story Buñuel tells seems very plausible: Mathieu left and returned to Conchita for a good reason. But the madness slowly emerges when the act is repeated over and over in an extremely subtle and sadomasochistic variation. For Mathieu, the predictable course of events was a freedom, liberating him from a chaotic and irrational world beyond his control. A group of revolutionaries is present in all of Buñuel's films: Mathieu has to deal with a terrorist gang (named "Baby Jesus Revolutionary Army" in a great irony conceived by Buñuel) ). They assassinate one of Mathieu's fat cats at the beginning of the movie and come back to execute Mathieu at the end of the movie. Returning to his roots in Spain, Buñuel is a true anarchist. He never questioned the need to destroy the old system of politics, religion and culture. But at the same time, as an inherently contradictory director, he finds a particular grace and beauty in Mathieu's artificially constructed existence: as a member of the bourgeoisie, he also has that Discreet charm. "Hazy Desire" is the work of a director who has full control over the medium. After 50 years in film, Buñuel has achieved a form of virtuosity. The only directors who can reach this level and are still making films are Alfred Hitchcock and Robert Bresson. From his finely stylized sets—evenly lit, too bright for “real life”—to his ballet-like choreography of actors and cameras, Buñuel just seems impossible to make mistakes. He usually maintains a discreet distance between the camera and the action, and in doing so creates an image that appears to be open and inclusive but is fraught with danger and uncertainty—a bed that appears unnatural in a room, Tables that are too rigid. "Hazy Desire" is a great movie, and it was the first movie we saw in Chicago that made me think for a long time. Even if it doesn't have the edge as Buñuel's other two masterpieces -- Tristana and The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie -- it's certainly a masterpiece. After the momentary 1978 hit "Encounters of the Third Kind" or "The Unmarried Woman" was forgotten, "Hazy Desires" will still be hotly discussed and loved years later.

View more about That Obscure Object of Desire reviews