Translated from James O'Connor's review published on GameSpot, the original link is attached at the end of the article.

In the fourth episode of The Midnight Gospel, the protagonist Clancy perfectly sums up the central conflict of the show: "For me, sometimes I really feel like I've lost the ability to listen." To Trudy Goodman (a real-life mindfulness coach who plays a bereaved knight on the show), "I was so caught up in my own gibberish that I couldn't listen to anyone else anymore. Just pretending to listen: I nod, look at each other, pretend to pay attention, etc., but I don't hear every word they say."

And at the end of the episode, Clancy and Trudy defeat Prince Jam Roll (a little devil who eats people with his ass).

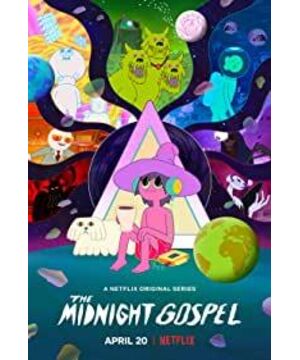

The process of watching "Midnight Gospel", for the audience, is itself a challenge to keep yourself focused. It bombards audiences with examples, citing philosophical treatises, throwing out existential musings, historical musings, and powerful emotional punches. At the same time, on a visual level, it fills the audience with strange, vulgar, and comical images. It's the kind of show that takes at least two more viewings to understand - the first time watching the bizarre animation itself, and the second time listening carefully to the dialogue between the characters.

When the characters on the show discuss their perspectives, their way of life, and how they find their presence in a chaotic world, the discussions are insightful, beautiful, and fused with philosophy, spiritualism, and history. At the same time, animators are given full creative freedom. They create wild, nightmarish images around characters. It feels like the audience is being pulled along two very different paths at the same time, and the effect on the brain is bewildering and shocking. At its best, it feels magical—a complex, absurd show that challenges you, moves you, and confuses you.

For example, in the first episode, Dr. Drew Pinsky and Clancy delved into psychedelics, drug addicts in America, and meditation. Clancy turns into a different figure in each episode, in which he is the muscular giant, and Pinsky's "Glass Man" is the little president (pinky little stature) of a world that is experiencing visual on the magnificent, growing zombie tide. The two characters engage in calm, in-depth conversations, occasionally mentioning everything around them, and chasing away zombies that come close. They take refuge in a shopping mall, help a woman give birth to a baby, and are chased by a giant monster. It's both striking and weird, and it's easier to understand on a second viewing. This is also one of the more direct plots in the play. While in some episodes they explore more interesting content than others, The Midnight Gospel is by no means a boring, gigantic number of lectures.

In other episodes, the connection between the protagonist and the animation is more explicit. In the fifth episode, Clancy talks to a prisoner in a galactic prison (her tongue is bitten) through a soul bird. While they discussed Hindu Dharma, the prisoner was being killed repeatedly, going through a cycle of life and death, each time her heart was weighed and compared with feathers. It's like Groundhog Day, but the discussion is more serious and weird, not to mention the stunning visuals. The show's frame-by-frame animation style reflects the unique expression and stylization of the art. Ward's signature style lives on in a world full of blood and genitals. But fans of Adventure Time will find the two shows are completely different things. The Midnight Gospel is disgusting at times, but never repulsive or nauseating—meaning there is a meaning in every bout of violence, nudity, and gore.

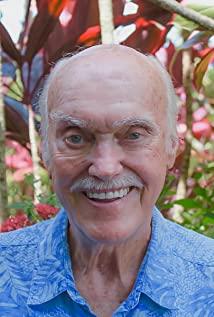

In the final episode, all of Clancy's disguise is removed. He becomes Duncan and discusses with Duncan's dying relatives "what is the real 'now'". In the show, the line between reality and fiction is blurred, and the interviewees, although ostensibly living on an alien planet, often mention that they are from somewhere in the United States, and often refer to Clancy as Duncan, while Clancy will laugh correct. And when I stumbled across that the show's premiere was on Duncan's birthday, that line was completely shattered, and none of this seemed like a coincidence. As separate people and entities, viewers will see Clancy and Duncan co-existing at the same time. It's an unusually emotional whiplash—"I laughed, I cried" couldn't be more appropriate here. When the play reaches the most absurd moment, it shows the most sincere emotions.

It's unclear how much of the show is scripted, or if it's just improvisation, as Duncan usually does when he interviews people. But he would have his guests pretend to be a giant deer dog about to be crushed by a meat grinder. But none of that matters, because the ideas the show conveys are more meaningful than the way it was made. To attribute "Midnight Gospel" to "about" anything is too one-sided, it's more like asking viewers to take it all in, like finding focus in a chaotic, difficult world. It requires you to find a way, when the world is collapsing around you, you have to find a way to be present, to pay attention, to really listen.

Original link

View more about The Midnight Gospel reviews