(This article is the final report of a course "From Novels to Movies" I took last semester)

Since the birth of the film, many films adapted from novels have been made, including many famous works. These adapted films have solid textual support from the original works, but after all, movies are an audio-visual-based art form different from literature. It is a masterpiece, and it is destined to be unable to escape the shadow of the original. However, there are also many adaptations among them, which are reinterpreted on the basis of the original work, which not only obtains solid text support from the original work, but also enriches the text and makes the film itself an independent artistic masterpiece. Here, I will analyze Kafka's "The Trial" and Orson Welles' "The Trial" to reveal that the latter is actually a "loyal betrayal" of the former. While retaining the outstanding artistic style of the works, Very different answers to the same question.

The novel "The Trial", the first betrayal of loyalty

Kafka

The 20th century was a turbulent century. The rapid development of modern science represented by physics made people marvel at the great achievements of reason. However, the two world wars and the massacres during World War II made people start to think about the boundaries of reason. The 20th century became a great and unique century. Scholars in this century are not only unique in intellectual history, but also have distinct personalities in the same period, such as Heidegger, Camus, Sartre and Kierkegaard, who are also existentialists. But if only one person can be selected from this era to represent this century, for me, Kafka is undoubtedly my first choice.

Kafka was born in Prague in 1883 to a fairly wealthy Jewish family, but his father's strict discipline from a young age left Kafka with great psychological trauma. Kafka, who later earned a Juris Doctor degree, worked for an insurance company, and he did his due diligence during his work, but he kept writing secretly. In this sense, he was indeed an amateur writer. Most of the articles he published during his lifetime were submitted only after repeated pleas from his friend Brod. However, what Kafka did not expect was that his writings earned him a huge reputation after his death and influenced him throughout the century.

betrayed testament

Before his death, Kafka asked his friend Brod to burn all his manuscripts after his death. However, after Kafka's death, Brod edited and published his manuscripts, including three novels, "The Missing Man", "The Trial" and "The Castle". Facing the doubts of others, Brod defended himself: "If he really wanted to destroy his manuscript, he would not ask me."

So, why did Kafka ask his friends to burn all his works before he died? Moreover, most of Kafka's works were published after his death, and the works published during his lifetime accounted for only a small part of his total existing works. The answer to this question may be found in the text of his own works. The hungry artist in "The Hungry Artist" seems to be himself——

They were sitting in a corner away from the Hungry Artist, playing cards and deliberately giving him a chance to eat. They always thought that the Hunger Artist had a trick to get some inventory to fill his stomach. The starvation artist was really miserable to meet such guards, who made him depressed and brought a lot of difficulties to his starvation performance. Sometimes, despite his weakness, he tried to sing loudly while they were guards, to show the gang how unjust their suspicions were to him. But it doesn't help. These guards even admired the high spiritual skills of others, and they could even eat while singing.

But for another reason, he was never satisfied. Perhaps his thin body was not caused by hunger at all, but because of his dissatisfaction with himself, so that some people did not come to the starvation show out of sympathy for him, because these people could not bear to see him being tortured. Tormented look. In fact, he understands that starvation performance is extremely simple and the easiest thing to do in the world, which I am afraid that even the connoisseurs do not know. Hunger artists are outspoken about this, but people just don't believe it.

In a sense, this is probably a portrayal of Kafka himself. Art is his only pursuit, for which he can burn his own life to the ground. Writing was in a way his way of praying and repenting. This is also the most attractive part of his works. His works are the result of thorough self-expression and self-exploration. Although Kafka is not a professional philosopher, his sensitive nerves and sentimental thoughts are acutely He captures the anxiety and confusion of human beings in the 20th century and integrates them into every word of his works. Therefore, when Kafka's physical body is about to die, there is no need to keep the traces of himself left in the mortal world. Of course, like his works, the motive for burning the manuscript is by no means a single one. Perhaps it was Kafka's almost harsh standards for literature, perhaps he was worried that his unfinished exploration would bring more pain to future generations, or perhaps he hoped that he would His heart has been hidden in the world forever, and we have no idea. But what we can know is that Brod made Kafka known to the world, and even became a representative figure of modern novel writers, allowing us to have a glimpse of this fragile heart that shares the pain and confusion of modernization with us, Let the great philosophers of the 20th century such as Arendt, Camus, Sartre and Benjamin take turns to prescribe various prescriptions for the modern diseases diagnosed by Kafka, and let modern people see from Kafka's writings This kind of betrayal can be said to be "loyal" to the spiritual condition of the times and to find its own shadow in it.

who is being judged

Kafka's works are often allegorical writings, any kind of thought can find its own shadow in Kafka's works, but trying to explain Kafka's works with any single theory will not work. . Take The Judgment as an example. Some people see the revelation of religion in it, some people see the judgment of patriarchy, and some people see Kafka's emotional entanglement, but among so many explanations, I personally Prefer the existentialist interpretation of The Trial - Kafka's The Trial is actually a description of a person's search for meaning and ultimately complete alienation.

The novel begins with

Someone must have falsely accused Joseph K, because, "He didn't do anything bad and was suddenly arrested one morning"

This corresponds exactly to what Camus said in The Myth of Sisyphus, the beginning of a man's awakening (just in the novel, Kafka gets up, rings the bell as usual for breakfast, only to call "arrest" "His people—that is, the beginning of all thinking), the moment of existentialism arrives

Suddenly, everything collapsed. Wake up, commute, work four hours, eat, commute, then work four hours, eat, sleep, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, always on a rhythm—most of the time we That's how it came. But one day, we start to think "why", and it all starts with this surprising boredom.

Obviously, Kafka's "arrest" was not because of a general criminal offense, nor because he violated the usual laws, it was all a trial of himself inwardly, as we can see, appearing in the novel Each of the characters is more or less related to the law or the court. These people are either court staff or they are involved in K's case. Even K's neighbor, Miss Bistner, said after learning that K was arrested. "I'm going to be a clerk in a law firm next month." It can be seen that the courts in the trial of K are everywhere, everyone submits to his authority and every corner of social life is intervened by him. If you want to find a corresponding thing for the court, you can think of the court as the sum of all human cultural constructs. As a field that is subject to various disciplines in all aspects, law is naturally the best representative of the achievements of human civilization that honor "rationality". It should come as no surprise then that all are under the control of the courts - each of us is subject to various disciplines from cultural constructions, even the seemingly creative painter Titorelli under the control of the court.

As an "awakened person", K has naturally become an "outsider" and may feel "disgusting" about everything he is accustomed to. For example, K felt "suffocated" in the court's office, but the staff in the office did not feel it, but felt uncomfortable with the fresh air outside. Sad for the businessman who surrendered to the lawyer, after he rejected the lawyer's defense (rejecting the disciplines constructed by human culture), and some time after the parable "At the Door of the Law" was exchanged between the church and the priest , was taken away and executed by two court clerks (finally gave up the fight and was socially alienated).

Of course, any attempt at a single interpretation of Kafka's work is doomed to fail. Perhaps the best way to read Kafka's work is not to find out what "meaning" Kafka was trying to convey, but to feel the loneliness, helplessness, and despair between the lines - just as we do in modernity. the way you feel in your life. But an interpretation of it is necessary here, which helps us take a comparative perspective below, deepening our understanding of the original while analyzing the film.

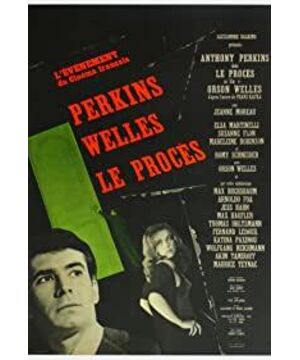

The movie "The Trial", the betrayal of the second loyalty

Wells himself

As long as you are a movie fan, it is impossible not to have heard of Orson Welles and his "Citizen Kane". The fledgling Wells made such masterpieces as "Citizen Kane", which makes people sigh that genius may be possible. does exist. Not only as a director, Wells' performances in films like The Third Man are also impressive. But since "Citizen Kane", although Wells has gained a great reputation, he has to be subject to the big studio system and let his efforts be wasted by capital. "The Trial" is a rare Wells possession Full authorship with full control over the film. Despite mixed reviews, Wells himself said, "Whatever you say, this is the best movie I've ever made."

betrayed original

Benjamin once commented on Kafka: "The Ten Commandments say that you shall not make an idol for yourself, nor make any image as if it were in the heavens and the earth, and the things under the earth and in the water. Kafka is the best to obey. Writer.", Benjamin may have made such an assessment because of the vagueness and lack of clarity of Kafka's language. However, Wells wants to put "The Trial" on the screen at this moment, from text to audio-visual, naturally he can't reproduce the essence of the original work. However, Wells, who is one of the great directors, took a different approach and reinterpreted the novel with a film - an exposure and resistance to totalitarianism, although in a sense he "betrayed" the original book of "The Trial", But it was a betrayal of respectful loyalty. Below, we further highlight this by conducting a careful analysis of both texts.

Comparison between the novel "The Trial" and the movie "The Trial"

Prologue, Interpretation of Dreams

Before starting the plot of the novel, the movie inserts a narration from the title, which comes from the dialogue between K and the priest in the penultimate chapter of the novel, but this fable was once called "In Front of the Law" before Kafka was alive. published separately. It has long been regarded as the key to unlocking the mystery of The Trial.

In the beginning, we see a slideshow of stills with a voice-over - which Wells himself dubs (in fact, the lawyer in the film is also played by Welles himself, which makes the film's The lawyer, who seems to have some kind of control over and off the screen beyond any character in the film), Wells added after telling the story—

This story comes from a novel "The Trial". It is said that the logic of the story is the logic of dreams—a nightmare.

Then, in the next shot, the protagonist K wakes up from a deep sleep, which corresponds to the "dream"-whether K wakes up and returns to reality or enters a dream.

The "dream" in the film is also reflected in some Freudian details. For example, in the interrogation at the beginning, most of the film involves Miss Bistner next door, but this is not the case in the novel. The more obvious implication lies in K's slip of the tongue and the agent's slip of the tongue

That's my pornography... my phono...my photography

No, it's not really circular. Ovular.

So the film almost explicitly calls for a Freudian psychoanalytic critique of it, but because of my theoretical level, here I have decided to leave this challenging task to others. But it can be seen that sex is an important theme in both the novel and the film.

time, space

In the novel, K was arrested on his birthday and executed on his birthday. Naturally, this time was not an unintentional act of Kafka, but implied that this was K's fateful trial, awakening on "birthday", and then on "birthday" Death (complete alienation, the death of the ego) makes the novel appear more philosophical. But this is not specified in the movie, on the contrary, there is no obvious time specified in the movie. On the contrary, novels often have a description of time specific to the point, and through the description of time, it reflects the endless trial process and the torture of people (so some translations translate the title of the book into "Proceedings", emphasizing the process during the period. ). Whereas in the film, the passage of time is ambiguous, with most scenes taking place indoors, and the rare outdoor scenes mostly taking place at night.

Corresponding to the ambiguous passage of time is the treatment of space in novels and films, both of which make spatial relationships somewhat ambiguous. First of all, whether in novels or movies, most of the content takes place indoors - as in modern life, when we go outside, we just walk from one building to another, and buildings serve as one after another. Functional venues are the best exhibition venues for alienated modern people. The workplace of K presented in the movie is a huge office, and the office accommodates thousands of employees. When it comes to off-duty hours, everyone immediately packs up and leaves like a machine (can't help but think of the scene at the beginning of "Metropolis". ), the life of the person who has been alienated to the extreme has been completely isolated from his daily life (of course, compared with the current 996 - life is completely occupied by work - it is already very benevolent) and between people indiscriminate and substitutable. But in the film, the effect of this treatment not only highlights the visual effect, but also has a hint that privacy has nowhere to hide in modern life, which is not without help for the film's re-elaboration of the novel.

In novels, the process of characters moving between places is often just a brushstroke, but in movies, the process of characters moving between places is simply edited out. Characters often leave one place and immediately enter another place. It is worth mentioning that the filming was shot in multiple cities - Zagreb, Paris, Milan and Rome, and sometimes multiple different locations were edited together, although it is logically possible to The narrative logic of the image is perceived by the audience, but invisibly creates a strange sense of space. For example, the following dialogue scene, although continuous in the film, was shot in Rome, Paris and Milan respectively. Although the excellent editing made the audience not aware of any abnormality, it subconsciously split the continuous space , further enhancing the sense of absurdity.

In the movie, there have also been scenes where characters appear outdoors. For example, in the scene where K was arrested at the beginning, K escaped from the room to the balcony, but he was still unable to escape the interrogation of the detective, and even made himself suffer from others in the opposite building. look.

In the scenes where other characters are outdoors, the characters often occupy a small part of the picture, and at the same time, compared with the huge buildings, it shows the insignificance and powerlessness of the individual, which is exactly what Sartre said "people in the desert" the absurdity of finding meaning".

style, expressionism

The language style of Kafka's original novels is plain and even a bit "dry", and its obscurity mainly comes from the logic and story of its narrative rather than words. In fact, the most fascinating thing about Kafka is that he can always say the most amazing sights in the most plain and natural tone. Much of the story's information is revealed through lengthy conversations between characters. For example, the description of the court system is almost always done through K's conversations with different court staff. At the same time, the rhythm of this constant dialogue and story progression is often depressing. The protagonist's name is Joseph K, but in contrast, the other characters have a full name, which reflects the non-uniqueness of the protagonist - he can be anyone, me, you, or everyone around you. At the same time, the description of the environment in the novel reflects an allegorical ambiguity - no specific country or city is specified, nor a specific era, and the daily life described during the period seems to be in any country today. Can't see too much inconsistency. It can be seen from this that Kafka's world is to some extent eternal - as long as the crisis of modernity has not been resolved, Kafka is still describing the present world.

By contrast, Wells' "The Trial" is full of film noir flavors. For example, the attire of an agent, which is full of the image of a film noir agent. In contrast, Kafka's original description of the agent's color is: "Wear a fitted black dress with many frills, pockets, drawstrings and buttons like a travel suit, in addition to a belt"

At the same time, the identity of Miss Bistner next door has also changed from a typist to a dancer in a nightclub, which is also a very typical character in film noir. The multiple shots at the same time are reminiscent of classic noir films such as "Double Indemnity" and "The Third Man"

And the treatment of lighting in the film is also full of the taste of film noir——

Even in a sense, "The Trial" is a film noir - the protagonist is the detective, he wants to find out what kind of crime he has committed, in the process of searching, he falls into one whirlpool after another, and finally gradually discovers Get the truth out—sin but not a crime. If so, the classic noirs "North by Northwest" and "Death Spiral" seem to have a bit of Kafka.

The choice of this style is not entirely out of Wells' personal preference, because Kafka himself is one of the representatives of German Expressionist literature, and uses the form of film noir, which is deeply influenced by German Expressionism, to express Kafka's works. , does have his reasons.

But it has to be said that Wells is not alone (of course, he is probably the most famous director of all) famous directors trying to interpret Kafka's works on the big screen, and different directors have different audiovisual language. The trade-offs are also different.

The film "Class Relations" based on Kafka's "The Missing" is directed by Daniel Huyer and Jean-Marie Straub. The film still uses black and white photography, which is more in line with a feature of Kafka's work - the lack of "color" (of course, this is definitely not a derogation, but a praise for his unique style), which also creates a kind of Allegorical alienation. But compared with Wells' expressionist art design and mise-en-scene, "Class Relations" tries to restore the dry language of Kafka's original works - fixed camera positions, zombie-like performances by actors, deliberate and abrupt shots Move and clip. At the same time, a sense of alienation from the audience is intentionally created. Even the unfinished ending of Kafka was brought to the screen. It can be said that "Class Relations" is a film that very restores Kafka's original work - both in content and form, its own artistic value is also very worthy of recognition.

Haneke has also adapted Kafka's "Castle", which to some extent is like a continuation of the style of "Class Relations", but the degree of stylization is far less high, and at the same time, it uses a lot of narration to promote the narrative

Koji Yamamura changed Kafka's short story "The Country Doctor", which used exaggerated and deformed pictures to interpret Kafka's works, and also used a lot of characters' inner monologues to promote the narrative

Soderbergh is shooting a film called "Kafka", this time, he made Kafka the leading actor, but this is not a biopic, but a combination of Kafka Fiction and life, with a highly dramatic film. In this film, Kafka literally turns into a film noir agent and discovers the surprising secrets of "The Castle." In general, the film also mainly follows the style and narrative structure of film noir.

Among the films shown above, in terms of artistic value, "The Trial" and "Class Relations" stand out, but the two have exactly the opposite style - "The Trial" uses expressionist art direction and scenes. Scheduling allows us to directly feel the characters' inner struggles in an absurd world, while "Class Relations" makes us feel the absurdity of the film's text and audio-visual itself through the deliberate alienation. But are any of them closer to Kafka's original, I think both are equally close, and there is no difference - the language of Kafka's original is plain, but its content is absurd, but this kind of The absurd does not come from the external environment, but from the inside of the person - why is K arrested? Why was K suddenly executed? Why is K so dependent on women? Why did the priest tell K that story? The actions and thinking of the characters are also contrary to our daily behaviors - from an existential perspective, this reflects the irrationality of the world and the irrationality of people. But the things around the characters and the things they experience are not necessarily peculiar. So I think Kafka's work is about "absurd people in a normal world", Wells is about "normal people in a ridiculous world", and Class Relations is "absurdly presenting people The fact of being in the world", from this point of view, neither of them fully - certainly not at all necessary and impossible and should not - restore the style of Kafka's original, but their respective styles are enough to make the adaptation The work acquires artistic value independent of the original novel.

The End, From Metaphysical Kafka to Prophet Kafka

When a story changes between different mediums, it is inevitable to adapt the original to a certain extent. For "The Trial", the biggest change is the order of the chapters, but this is not a problem - because There was no order among the chapters of Kafka's original manuscript, and it was Brode who later published the chapters in their current order. In fact, the biggest "betrayal" of the movie to the original is the handling of the ending - in the original, this is how K's execution is described -

The first man handed the knife over K's head to the second, and the second returned the knife from K's head to the first. K is now well aware that when the knife is passing over his head, he should take the knife and insert it into his chest. He didn't do that though, just turned his head and looked around - his head was still free to turn. He couldn't completely overtake them and complete all their tasks for these two people. This final failure should be blamed on himself as he doesn't have the strength to do it. His eyes fell on the top floor of the house next to the quarry. There was a flicker of light, as if someone had turned on the light, and a window opened abruptly. A man's body suddenly sticks out of the window, and his hands are far out of the window; because he is far away and standing high, his figure is blurred and cannot be seen clearly. Who is this guy? a friend? A good man? A sympathizer? Someone willing to help? Is it just him? Or the entire human race? Will someone come to help soon? Has the previously overlooked argument in his favor been brought up again? Of course, there should be such arguments. Logic is undoubtedly unshakable, but it cannot stop a person who wants to live. Where is the judge he has never seen? Where is the Supreme Court that he never got into? He raised his hands and spread his fingers. However, one of the companions had already grabbed K's throat with both hands, and the other had inserted the knife deeply into his heart and turned it twice. K's eyes gradually blurred, but he could still see the two men in front of them; face to face, watching this final scene. "Like a dog!" he said; he seemed to mean: he is dead, but the shame will remain.

It can be seen that at the last moment, in the face of death, K in the novel also treated it negatively, and even said that "this final failure should be blamed on himself, because he did not have enough strength to do it." The idea of "Like a Dog" at the end is to portray K's final resistance failure in a somewhat comical feel, full of dark humor. However, in the movie, Wells completely changed the meaning of the ending - when the agent handed the knife to K, K refused to do it himself, but firmly said: "You must do it yourself." However, the two executioners climbed into the pothole and chose to kill K with dynamite. And when the explosive fell into the pit, K picked it up. Whether K wanted to throw the explosive out of the pit to do his best for himself, or whether he wanted to use this gesture to show his final unyielding, we don't know, because then As soon as the camera turned, the explosives exploded, forming a cloud like an atomic bomb mushroom cloud in the air - but no matter what, we can know that at the end of the movie "Trial", K fought to the last scene. In a sense, K in the movie loses worse than in the novel. K in the novel is left with a whole body, and K in the movie can be said to be destroyed in a physical sense; but in another way In a sense, K in the movie wins again, unlike the K in the novel who loses terribly - K in the movie retains his final dignity, as Hemingway said, "He was defeated, but not defeated. ".

Not only at the end, the difference between the K in the novel and the K in the movie is in fact very apparent throughout the movie. K in the novel is sensitive, suspicious, and even a little cowardly, and Kafka endowed him with an anonymous and alternative identity for modern people. With the development of the novel, K is more and more in a passive position. At the same time, the resistance is becoming more and more passive, relying more and more on external forces, and even begins to doubt whether he is really guilty, and begins to think about his past to find the crime. However, in the movie, K, played by Anthony Perkins, looks like an American-style lonely hero from the beginning to the end, a decisive and unyielding image that never yields and vows to find out the truth, which is very unique. And, with the development of the film, K's resistance became more and more intense, and the rhythm of the film became faster and faster. Until the last execution is the last and most fierce resistance.

Why did Wells deal with the imagery in the original work like this? In an interview, Wells talked about his handling of the ending: "The Trial was written before World War II, if Kafka lived After World War II, after the unprecedented Holocaust of the Jews (Kafka was also a Jew), I don't think he would keep this ending."

In fact, apart from the atomic bomb mushroom cloud-like smoke at the end, there are more obvious reminders of the background of World War II in the movie-

Before K entered the courthouse, K passed a crowd of scantily clad people with number plates hanging on their chests, and we can immediately see that this is a clear reflection of the concentration camps and the Holocaust in World War II. Such a scene in front of the court seems to tell us that the court in the movie is more like the insinuation of various totalitarian governments that have existed in history compared to the various metaphysical constructions of human civilization. In fact, in the reinterpretation of Kafka after World War II, Kafka was combined with the historical background at that time, and Kafka was regarded as a prophet, and Kafka changed from a metaphysical Kafka. became a historic Kafka. As Arendt commented:

The prison priest's words in "The Trial" reveal that the fate of the bureaucracy is the fate of necessity, and they themselves are one of the clerks. But as a clerk of necessity, man becomes an agent of the natural law of decay, thereby reducing himself to a natural instrument of destruction, which may be accelerated by the misuse of man.

It is because of this historic reading that Kafka's novels were banned in East Germany after World War II. Many who have suffered from totalitarian regimes during wartime have read the absurdity of the real world from the absurdity of Kafka's novels.

Of course, such an interpretation may be suspected of interpreting Kafka's works one-sidedly, but this is also the greatness of Kafka's works-it does not describe a specific theme, but comprehensively reflects the modernity of modernity. The fate and confusion of mankind in the process. Bowman's "Modernity and the Holocaust" points out that the Holocaust actually reflects the other side of modernity, and it is precisely because of the elements of modernity that the Holocaust becomes so cruel. It is also because of the modern type that more and more bureaucratic organizations appear, so that a special word - Kafkaesque (Kafkaesque) appears in the English dictionary to describe the modern people's attitude towards Kafka. Fiction is an increasingly everyday experience. From this point of view, this is an excellent reinterpretation of Kafka's work in one aspect - the embodiment of the symptoms of modernity described by Kafka into specific diseases - great Holocaust and totalitarianism.

Therefore, for Wells, he is not willing to succumb to the oppression of modernity like Kafka's K, but rises up to resist, one person fights against this huge system - arrested for no reason, not given Courts of any chance of defense, cumbersome bureaucracy, K represents an unyielding individual under totalitarianism.

It is worth mentioning, however, that in the fully positive film, the ending lacks a key positive element - the lamp on the high-rise building. At the end of the novel, K sees someone beckoning to him from a tall building, which is deleted from the movie. What this man is alluding to, like Arendt's appeal to the sincere and concrete love of the individual for the individual, we do not know. Whether Wells deleted this scene to accommodate the empty scene at the end, or whether he wanted to call on individuals under totalitarianism to take responsibility for individual disobedience, we do not know. But it can be seen that even Kafka, at the despairing end of the novel, has left us with a glimpse of the dawn of the dark tunnel of modernity.

in front of the law

Whether it is a novel or a movie, "In Front of the Law" is regarded as a very important fable in the movie. Whether in the movie or in the novel, K was executed shortly after communicating the story with the priest. It can be said that this fable is to some extent the court's judgment on K. Likewise, when the subject is changed, we see that this paragraph must also change.

In the novel, K was originally going to the cathedral to receive a client, and in the church, when K heard the priest's cry, he actually wanted to leave, but in the end gave in.

He is still free for the time being, he can continue on his own path, and he can slip through the small dark wooden doors not far ahead and run away. This would show that he didn't understand the shout, or that he understood it, but didn't take it seriously. But if he turned around, he would be caught, because that would be an admission that he did understand, that he was the one the priest was calling, and he was willing to bow his head. If the priest called K.'s name again, he would surely go on; but, though he stood and waited for a long time, there was no sound; he could not help turning his head a little to see what the priest was doing.

After listening to the story told by the priest, although he opposed the priest's point of view, he always expressed it carefully, and finally got tired of the debate and said goodbye to the priest in a friendly way:

"No," said the priest, "it is not necessary to admit that everything he says is true, but to accept it as a necessity." "A depressing conclusion," said K., "that would make a lie become the norm."

K said this sentence in a decisive tone, but it was not his final judgment. He was too tired to analyze the conclusions drawn from the story one by one; the mass of ideas that came out of it was foreign to him, incomprehensible; to the judges it was a fitting Discussion topics, but not so for him. The simple story had lost its clear outline, and he wanted to drive it out of his head; the priest was now expressing a delicate emotion, and he listened to K., silently listening to his remarks, although he undoubtedly disagreed with him. View.

They paced back and forth in silence for a while; K, next to the priest, did not know where he was. The light in his hand had long since gone out. The silver statues of several saints flickered in front of him because of the lustre of the silver itself, and immediately disappeared into the darkness again. In order not to depend too much on the priest, K asked: "Are we not far from the gate?" "No," said the priest, "We are still far from the gate. Do you want to go?" Although K. He didn't expect to go at that time, but he replied immediately: "Of course, I should go. I am a bank assistant, they are waiting for me, I am here just to accompany a financial community from abroad. Friends visit the cathedral." "Okay," said the priest, holding out his hand to K. "Then you can go." "But it's so dark that I can't find my way by myself," said K. "Turn to the left and go straight to the wall," said the priest, "and follow the wall, don't leave the wall, and you'll come to a door." The priest was a step or two away from him, and K shouted again : "Please wait." "I'm waiting," said the priest. "Do you want anything else from me?" K asked. "No," said the priest. "You were very good to me," said K. "You taught me so much, but now you let me go away as if you didn't care about me at all." "But you must go now, ' said the priest. "Okay, let's go now," said K. "You should know that I am helpless." "You should know who I am first," said the priest. "You are the priest in prison," said K. He groped and approached the priest again; he did not have to rush back to the bank, as he had just said, but could stay a little longer. "That means I belong to the court," said the priest, "why should I make all kinds of demands on you? The court doesn't make demands on you. Come and it will receive you; go and it will let you go. ."

However, in the movie, K's performance in this section is completely opposite. In this section, K walks under the pulpit with alertness after hearing the priest shout his name loudly. The rest of the story is narrated by K's lawyer, played by Wells himself. This time, his lawyer used a projector to project a slideshow from the opening of the film to tell the story. However, halfway through the story, K said that he had heard the story and took the lead, and began to tell the story. Take the lawyer's words to tell the story. However, in the end, K denied everything the lawyer said with an unquestionable tone, and vigorously fought back against the lawyer's argument.

ATTORNEY: Some commentators have pointed out that this person came to the door voluntarily. K: So we should just put up with it? Accept the fact? Attorney: We don't have to require what is accepted to be true, just that it is essential. K: God, what a sad conclusion to make lying the rule of the world! Attorney: Attempt to contempt of court! Are you going to get away with proving yourself insane with this madness? Do you want to look like the victim of a conspiracy, thus laying the groundwork for your sophistry? It's a symptom of insanity, isn't it? K: I am not a martyr! Lawyer: Not even a victim of society? K: I am part of society. Attorney: Do you think the court will acquit you of being insane? K: I think that's what the court is trying to make me believe. Yes, this is the conspiracy - to convince us that the whole world is crazy, chaotic, pointless, ridiculous! That's a dirty trick! So I lost, but you! You lose too! The whole world loses! Lost! So what? So can the whole world be declared crazy? Priest: You still don't understand! K: Of course, I am also responsible. Priest: My child! K: I am not your child!

The change in this passage is the inevitable result of the change in K's character and theme - compared with the passive acceptance of K in the novel, K in the film actively challenges the system that oppresses him.

In this section, during the slide show, K's shadow is projected on the slide that tells the story, as if K entered the story, standing in front of the door of the law in the story, but K didn't pay attention to one Another organization of gatekeepers went straight into the door of the law.

And when K made his impassioned dissent, the screen went all white - is this the law in the halls of law? There is only K in front of the screen—perhaps in the hall of law, it is everyone’s inner beliefs and pursuits.

When K left, what the priest said was actually dubbed by Wells as well, and here the identities of priest and lawyer are somehow interleaved - both of them wanting K to "confess" to his crimes, If lawyers represent various social constructions of human beings, then priests represent the discipline of religion. However, K completely gave up the illusion of religion with "I am not your son". (Also, the painter is also entirely voiced by Wells, a dislocation that adds to the absurdity of the whole film - you'll find where the different characters seem to have been seen in the film, which also suggests that they all have a relationship with the court. inseparable connection)

betrayed original

In this sense, Kafka was thoroughly betrayed by Wells, who turned the dirge-like depression and despair of the original into a hymn of active defiance. Kafka lamented the meaninglessness and absurdity of the world, but Wells shouted "Let us believe that the world is crazy is the most dirty trick"!

However, Wells's text and Kafka's text form an ingenious intertextual relationship - if Kafka is the one who raises the question, "In the life of modernity, the solitary, alienated and inexorable individual is Fate to avoid", Wells gave his own question on Kafka's problem, "Take responsibility as an individual, think forever and resist forever!" This is not only a critique of existentialism, but a The praise of existentialism, because according to Camus in "The Outsider", after awakening, the individual will be in the tension of "complete awakening" and returning to the shackles, and the solution given by Camus is - forever. to resist! Suicide is not a possible option, because it means accepting the absurd and giving up life as the only thing that has value—and the value of life comes from constant resistance, awareness of the absurd nature of the world, and constant resistance to it. Even from a historical point of view, Wells's prescription for modern totalitarianism coincides with Arendt's call - always maintain the freedom and dignity of the individual!

From this point of view, although Wells betrayed the original, it was also a loyal betrayal - he was loyal to Kafka's question and offered his own excellent answer. It forms a unique intertextual relationship with the original text. Rhein Phillip used this metaphor to describe the difference between Kafka's and Wells' images of K:

Kafka's K and Wells' K stand in front of the curved window of a corner store, admiring the artwork on display. They were lost in their own thoughts, completely unaware of what was going on at this noisy intersection. Suddenly, a loud noise pulled them out of their deep thoughts, and they raised their heads to see the deformed crowd and massive buildings reflected in the curved shop windows - approaching them like giant ghosts. They were all taken aback, and staring at the mirror made them tremble. Kafka's K immediately bowed his head to avoid the horrific sight, while Wells' K turned and disappeared into the street.

You shall not carve idols

In the movie, there is a sculpture, but we have not been able to see the true content of this sculpture——

This sculpture appeared twice, once before K entered the court for the first time, and a concentration camp-like crowd stood under the statue, and the second time was when K was finally executed, standing in the open suburbs.

So what exactly is this statue, we may be able to find clues from the conversation between K and the painter.

He took a piece of chalk from the table and added a few more strokes to the man's outline; but K still couldn't recognize it. "This is the goddess of justice," said the painter at last. "I recognize it now," said K. "She has a cloth over her eyes, and these are scales. But doesn't she have wings on her heels? Isn't she flying?" "Yes," said the painter, "I was instructed to draw it like this; it's actually a combination of the goddess of justice and the goddess of victory." "This combination is definitely not very good," K said with a smile, "the goddess of justice should stand firm, otherwise The scales are about to shake, and the verdict cannot be just." "I have to do what my customers tell me," said the painter. "Certainly," said K. He didn't want to offend anyone with his comments.

Due to the shallow outline, the goddess of justice seems to jump to the front of the picture, she no longer looks like the goddess of justice, or even the goddess of victory, but rather like the goddess of hunting who is chasing her prey.

Thinking of the time when this statue appeared in front of the court and K was executed, this statue is likely to be the deformed goddess of justice, which also fits with certain characteristics of this court.

In the movie, we also fail to see what the artist's painting looks like. We can only see the two people looking at the painting from the moment we arrive.

As we pointed out earlier, Benjamin praised Kafka as the writer who best adhered to the commandment of "no idols", and Wells seems to have taken this criticism to heart, so we can't be on screen either. See the true face of this statue. However, the reason why the statue was erected is nothing more than to commemorate the affairs represented by the statue or to preach the values it represents. However, this ghostly statue is completely invisible. It is not so much to convey a specific message. Rather, he conveys an unfathomable, unknowable and pervasive sense of oppression, like a court in this world.

When K was finally executed, from the church in the center of the city to the outskirts, the picture first appeared in the old streets full of history in the center of the city, followed by the newly built modern buildings, then the small bungalows in the suburbs, and then The statue appeared, and then the building completely disappeared, leaving only a vast landscape of nature. This statue is the last building that K saw - the last human construction, the last uninhabited suburb. At this time, not only does it appear without borders and constraints, but it also presents a sense of desert-like absurdity. And meaningless, this statue marks the boundary between the social construction of human civilization and the external existence. Once K passes this statue and is led into the absurd suburbs, it means his final struggle.

Prison of Light and Shadow

When K visits the painter, we can see that the painter's house is composed of loose wooden slats, which are obviously reworked in an expressionist style compared with the description in the novel——

The entire room, including the floor, walls and ceiling, is a large box made of unpainted wood planks with visible cracks between them. On the wall opposite K was a bed with blankets of various colors stacked on it. In the center of the room was an easel with a canvas covered with a shirt with sleeves hanging down on the floor. There was a window behind K. The fog filled the window. Only the roof next door was covered with snow, and nothing could be seen further away.

The light from the outside projected onto K and the painter through the wooden board, which seemed to be like a cage, trapping the two people firmly, showing that K was getting more and more embarrassed. The painter's striped pajamas also seem to reinforce this visual effect at this time.

And when K escaped from the court's office, he entered a long tunnel made of wooden slats. The light came in from the outside as if K was like a prisoner, escaping the chase and eyes of the children outside.

This hand-held shot, coupled with rapid editing and tense soundtrack, perfectly externalized K's inner struggle at that time. In the sewer chase behind, fast-forward was also used to make the whole chase more surreal. It is worth noting that the lens selection here is very interesting, the lens is always facing K, he is not looking forward, but keeps a few steps in front of K, which makes us unable to see the road in front of K, only to see K is dodging obstacles seemingly pointlessly. A shot below the sewer shows a panicked K avoiding obstacles while avoiding the chasing crowd, but due to the camera's angle, we can't see exactly what kind of obstacles are in front of K, only K Seems to be walking randomly. K's uneasy feeling is directly transmitted to the audience.

Similar tactics are not only used here, but also in K's first courtroom appearance and in K's pursuit of the law student who kidnapped the laundress.

In addition to the dialogue scene with the painter, another unique use of light is the scene where the two agents are punished in the utility room. The flickering lights, the characters appearing and disappearing, the hasty editing and unique camera angles further highlight the pain of the two tortured people and K's inner struggle.

Women in the shadow of patriarchy

The female images in Kafka's novels are always a topic that cannot be avoided in his works. In "The Trial", the main female images around K are K's neighbor, the washerwoman in the court, and the lawyer's maid. , and K and they all have a sexually entangled relationship in one way or another. On the one hand, K is so eager for women's love. After his arrest, the first person he found to talk to and help was his neighbor, and at last K kissed her when he left. However, this Shi K didn't even know what the neighbor's name was (K only knew her last name). In the movie, Wells changed the occupation of K's neighbor to a nightclub dancer, which further strengthened the implied meaning. At the same time, his actor's performance was also full of implied meaning. However, unlike the ambiguous relationship between the two in the novel, the movie The two eventually parted ways.

The court maid took this sexual suggestion a step further. During K's first trial, the law students publicly kidnapped her in the courtroom. When K returned to court, the two started a flirtation, but they were arrested again. The law student interrupted and kidnapped her. Here, the camera switches between the law student and K and the female worker, creating a sense of oppression.

And when K went to the lawyer's house, when the lawyer started talking about K's case with K's uncle, K went to have a tryst with the lawyer's maid. Here we can see that K has a childlike obsession and naive pursuit of female images, but they are all just traps one after another - her neighbors wanted to study law, but in the end they failed to help K. No matter what you do, the relationship between the two is also flat (in the movie, K is simply kicked out); the female court worker is still humbled by the court after flirting with K; and the lawyer's maid is not only the lawyer's vassal, but also It was to persuade K to plead guilty.

"If I tell you, I've paid too much," replied Leni, "please don't ask me what their names are, just take my advice, and don't be so stubborn; you can't fight the courts, You should confess your guilt. Confess when you have the chance. If you don't confess, you can't escape from their clutches, and no one can do anything. Of course, even if you confess your guilt, you won't be able to achieve your goals without outside aid; Don't worry about it, I'll find a way."

As you can see, these images of women are more or less associated with the courts—and the courts are the best representation of the patriarchal social construction of human beings. K tried every means to get a way out of this patriarchal construction from these female images, but failed again and again.

K: Goodbye Leni, thank you! Leni: You'll be back. K: Absolutely not. Leni: But you've got nowhere to go.

K's subsequent dialogue with the priest pointed out the ineffectiveness of K's efforts -

K: There is a lot of help, I just haven't looked for it yet. Priest: You are too dependent on outside help! Especially the help of women. K: Women are very influential.

Because although the female image has characteristics that are contrary to the patriarchal structure, it seems to be a way to escape the patriarchal social construction, but under the social construction, women are still subordinate to the patriarchal structure and live in the shadow of the patriarchy. So any effort by K to get help from the female image is doomed to be futile.

Find all defendants attractive. It's one of her quirks, she messes with all the defendants, messing with them. And when I gave her permission, she told me the story for my entertainment, without reservation. The accused is indeed charming. Being sued doesn't change their appearance. But if you know how to distinguish, you can recognize the accused in the crowd, and there is something in them.

In a sense, the attractiveness of the defendants to women may be precisely their questioning and challenging of the construction of a patriarchal society.

Summarize

Wells' film The Trial is not an attempt to reproduce Kafka's original novel entirely, on the contrary, Wells has made a certain but substantial adaptation of it, emphasizing the historicity of The Trial. Theme - Totalitarianism. At the same time, it responds to the questions raised by Kafka with the ending of the adaptation, forming a clever intertext with the original work. However, while eliminating most of the ambiguity of its theme, it still retains the ambiguity, surrealism, and absurdly depressing artistic characteristics of some of the original images. At the same time, the outstanding audio-visual and narrative make "The Trial" not only an excellent adaptation of "The Trial", but also an excellent independent work itself - although the publication of the "Trial" novel betrays Kafka, Wei Wei Russ's "The Trial" also betrayed the novel "The Trial", but both Brod and Wells, although they betrayed Kafka - but also the most loyal to Kafka.

references

Lev P. Three Adaptations of "The TRIAL"[J]. Literature/Film Quarterly, 1984, 12(3): 180-185.

Vatulescu C. The Medium on Trial: Orson Welles Takes on Kafka and Cinema[J]. Literature/Film Quarterly, 2013, 41(1): 52-66.

Stimilli D. Secrecy and Betrayal: On Kafka and Welles[J]. CR: The New Centennial Review, 2012, 12(3): 91-114.

Koch J. “The False Appearance of Totality is Extinguished”: Orson Welles's The Trial and Benjamin's Allegorical Image[J]. Film-Philosophy, 2019, 23(1): 17-34.

Goodwin J. ORSON WELLES” THE TRIAL: CINEMA AND DREAM[J].

Scholz A M. " Josef K von 1963...": Orson Welles''Americanized'Version of The Trial and the changing functions of the Kafkaesque in Postwar West Germany[J]. European journal of American studies, 2009, 4(4 -1).

Adams J. Orson Welles's" The Trial:" Film Noir and the Kafkaesque[J]. College literature, 2002, 29(3): 140-157.

Lesser S O. The Source of Guilt and the Sense of Guilt-Kafka's "The Trial"[J]. Modern Fiction Studies, 1962, 8(1): 44.

Politzer H. Franz Kafka and Albert Camus: Parables for Our Time[J]. Chicago Review, 1960, 14(1): 47-67.

Fort K. The Function of Style in Franz Kafka's "The Trial"[J]. The Sewanee Review, 1964, 72(4): 643-651.

Dern J A. Sin without God": Existentialism and" The Trial[J]. Interdisciplinary Literary Studies, 2004, 5(2): 94-109.

Hannah Arendt, "Kafka Reevaluation"

"On Kafka" by Walter Benjamin

Albert Camus, Hope and the Absurd in Franz Kafka

Modernity and the Holocaust by Zygmon Bowman

Sun Shanchun. Walter Benjamin's Kafka Interpretation[J]. Journal of Tongji University: Social Science Edition, 2007, 18(4): 14-19.

Huang Liaoyu. Kafka's Overtones——On Kafka's Narrative Style[J]. Foreign Literature Review, 1997 (4): 59-65.

Li Bo. The Interpretation of Kafka and His Works in Film [D]. Northwest University for Nationalities, 2015.

View more about The Trial reviews