Last Saturday, the VCD Film Promotion Association successfully held a viewing event for "The Lady of Sand" at the French Cultural Center. The following brings you relevant articles on "The Lady of Sand" to help you better understand the film.

Editor's note: "In the golden age of Japanese cinema, the devil master of Japanese cinema was born. The encounter of the imperial envoy Hiroshi Kawahara, Kobo Abe, and Toru Takemitsu is not only a tearing collision of film, literature and music, but also a model of the perfect fusion of multiple arts. With restrained and calm brushstrokes, the author of this article tells the unusual fate of the three people from the multiple dimensions of history and art."

[Original title] Edict Hiroshi Kawahara, Kobo Abe and Toru Takemitsu: A Unique Collaboration in Japanese Cinema in the 1960s

By | Giovanni Battista

Translation|VCD Promotion Association

The original text was published by film critic Giovanni Battista on his personal blog Cine-scope on December 28, 2013. This article was compiled by the VCD Film Promotion Association, and has been slightly edited. This article is about 3700 words, and it takes 9 minutes to read

If I were to choose the most glorious decade of film history in any country, I would definitely choose Japanese films of the 1960s without hesitation. If you're surprised, then remember that wealth and art are interdependent during this decade. The masters who started in the silent era (Ozu, Nara) are still creating masterpieces, while the directors born after the war (Akira Kurosawa, Ichikawa) are in their prime, producing countless peak works of their careers. In addition, the extraordinary creativity and power of the Japanese New Wave (Oshima Nagisa, Imamura), Suzuki Kiyomi's psychedelic and rambunctious jazz gangster films, and many great genre films converge here. What an astonishing time these are... In these films, some of the alien-like geniuses, some of the other films, made Japan in the 1960s an even more fascinating and worthwhile place to explore. Movie Mecca. An example of this is the four astonishing works produced by director Hiroshi Kawahara, writer Kobo Abe, and composer Toru Takemitsu: The Face of Others (1966), The Trap (1962), The Sand Girl (1964) ) and The Burnt Map (1968). These films are often classified as Japanese New Wave, but in my opinion, they are very different. Their physique is special and unique, they are the result of the cooperation of three ghosts, and they are different from any works in the world. Critics have compared them to European modernist art films of the same period, such as writer-directors Antonioni, Bergman, and Resnais. However slim the possibility of such a comparison may be, it underestimates the uniqueness of this partnership and the peculiar social soil of Japan in the 1960s.

The imperial envoy Hiroshi Kawahara was a professionally trained painter, and Abe Kobo wrote both drama and literature. Toru Takemitsu was a pioneering composer and music theorist. In the 1960s, how did these three people create a world-beating work that transcended their time? Especially in the 1950s, when the Japanese film industry adopted the most hierarchical studio system in the world, anyone who wanted to be a director had to go through a lengthy apprenticeship (usually up to five years) assistant director), meanwhile, there are hardly any independent films outside the big studios. So what happened in the 1960s that opened the door to filmmaking that used to be imprisoned? The landslides and fissures that occurred during this period will be a crucial part of my story. But let's start from the ground up and look at the land where these three future masters were born and raised - Japan.

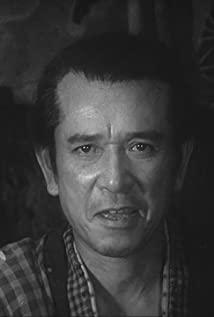

Edict Kawara Hiroshi was born in Tokyo in 1927. His father was Eji Kawara Sofeng, the founder of the Japanese Kussuki Ryu Flower Arrangement. Blue Wind is a progressive-minded artist who embraces a wide range of rivers. His creations have become a rare feat in the conservative traditional Japanese art world. Therefore, in the immersion of his eyes and ears, Echiji Kawara Hiroshi initially chose to study painting at the Tokyo Academy of Fine Arts.

Abe public housing did not come from the upper classes. He was also born in Tokyo in 1924, and later his family moved to Manchuria, where he spent his youth. In the future, people often say that the brutality of Japanese colonialism and the desolation of the puppet Manchuria have become part of the soul of his works. Anbe once said: "I stayed in Manchuria for a year and a half after the war and witnessed the complete destruction of the social order in Manchuria. This made me lose trust in everything that was inherent." After the war, he returned to Japan and faced the powerful The culture shock of his so-called home country is so alien to him that he develops a unique outsider perspective: "The place where I was born, where I grew up, and the roots of my family's generations are all different...essentially. , I am a homeless person, and my disgust for my hometown... probably stems from this." Since then, alienation and identity have gradually become the hallmarks of his work. The experience also foreshadowed his strong anti-nationalist sentiments—Abe was an internationalist, a man without borders, committed to abolishing the existence of nations and nations.

Toru Takemitsu was born in Tokyo in 1930. Since he was frail and sick from a young age, he spent most of his time at home, listening to US military radio, reading or listening to various kinds of music. Although it was hoped that he could continue his father's business and become a businessman, he developed an unprecedented passion for Duke Ellington and all kinds of jazz, and taught himself to be a composer. Western cultures that had been banned during the war flooded into Japan, and curious young Japanese began to crave them. In addition, after the war they grew up as adults, and they all longed to draw a line from the past. Young people of Toru Takemitsu's generation nailed Emperor Hirohito's extreme militarism to the pillar of shame. As he said: "Because of the Second World War, people's dislike of Japan continued for a while, and this cannot be easily eliminated. In fact, I wanted to become a of a composer."

Thus, transforming and redefining their country became a priority for postwar Japanese artists, writers, and thinkers to revive Japan. In this process, it is first and foremost to identify three relationships: tradition and modernity, Japan and the West, and society and the individual. Some want to learn from the experience of the West, and many also want to look back at Japan's ancient and blameless pre-war traditions, especially Zen Buddhism, and apply them to new art and thought. The art community is made up of like-minded artists and intellectuals from different backgrounds. They both want to blur the boundaries of different arts, experimenting and extremely innovative fusions of literature, painting, music, dance, photography, sculpture and calligraphy. In this atmosphere full of avant-garde and chaotic intersections, Edict Kawara Hiroshi, Abe Kobo, and Takemitsu Toru met in the depths of their souls.

In 1948, Taro Okamoto (a Japanese master architect) and Seiki Hanada (a playwright) established the "Night Club", a group dedicated to transcending the fetters of different genres and achieving true artistic fusion. Abe also became one of them. However, it did not achieve its original intention and ended up fragmenting into different groups. One of them is called the "Century Association", which was initiated by Abe himself and some members of the Night Club. Although the Century Society was founded by writers, it also opened its doors to painters and visual artists, Eshikahara Hiroshi being one of them. In 1949, the two met for the first time here and hit it off. The imperial envoy Hiroshi Kawahara later recalled his first meeting with Kobo Abe, describing him as "a man who was interested in all arts and sought to bring them together". At the same time, Toru Takemitsu was active in a similar pioneering group called "Experimental Workshop", which innovated in music, dance and multimedia performances. He and Abe and the imperial envoy Hiroshi Kawahara wandered in the same artistic circle.

In the 1950s, all three started their own businesses. In 1959, the imperial envoy Hiroshi Kawara spent four days in New York producing "Jose Torres", a documentary about a Puerto Rican boxer, for which Toru Takemitsu, a well-known score writer, was invited to compose the music. . At this point, the third corner of this artistic friendship has finally come together, and the emissary Hiroshi Kawahara is also very happy to have finally found a talented composer and a unique rhythm to match his images. Abe has also worked with Takemitsu on some radio dramas alone, which drew his attention to the composer's skill in using soundscapes to underpin the tone of language texts.

The Rise of Japanese Independent Films

Since 1910, Japan's major film studios (Toho, Shin-Toho, Shochiku, Daiei, Nikko, and Toei) have monopolized the industry, and despite the struggles of film artists, they have never been able to break the shackles. Japan's close alliance with the United States after the war was partly responsible for Japan's miraculous economic growth, and the 1964 Tokyo Olympics was a milestone moment for Japan's economy. But for the rebellious filmmakers and avant-garde artists of the new wave, Japan is experiencing a national postwar identity crisis.

After the war, the country still had no chance to breathe. From the extreme expansionist policy of the 1930s and 1940s (the Americans were regarded as the enemy at that time), it suddenly transformed into a capitalist country that relied on US funding and kowtowed to the United States. , In the eyes of these socially responsible artists, Japan is developing too fast and only cares about economic development, but does not take the time to take care of the unfortunate people in Japanese society. This sympathy was reflected in the films of the time, in their recurring themes—namely, people on the margins, alienation, and the search for identity. During the same period, New Wave directors would explore many of the same themes, but in very different ways, as Echiji Kawara Hiroshi and Abe Kobo. Compared to Imamura's gritty realism and Oshima's iconoclastic films about social outsiders, Edict makes Kawahara-Abe Kobo-Take Takemitsu's films more allegorical and obscure.

Founded in November 1961, the Art Theatre Guild (ATG), initially a distributor and exhibitor of foreign art films, soon began funding Japanese films with the intention of filling the gap in Japanese independent films. ATG represents the juncture between new wave artists who defected from major studios and experimental filmmakers with backgrounds in avant-garde documentaries and short films. The imperial envoy Kawara Hiroshi also admitted: "You can say that my film path was opened when ATG was born, and the film heretics finally found a home." Although ATG also belongs to Toho Corporation, it helps Japan Independent films found a channel for distribution and screening. Ten movie theaters are at their disposal, including the iconic theater in Shinjuku, a neighborhood in Tokyo that has since become home to many underground subcultures. ATG is a corollary of any of the film and art movements we've mentioned so far, and ultimately led to the collaboration between Emissary Hiroshi Kawahara, Kobo Abe, and Toru Takemitsu, which gave birth to truly great work.

A one-of-a-kind collaboration

Film is not only a mass art, but also a process of innovative fusion of visual, language and auditory/musical elements. In film, you can find an art form that was familiar in the past and become a familiar one. But something completely different. Artists and technicians in different fields use their unique talents to influence and change the same work. Therefore, for the imperial envoy Hiroshi Kawahara, Kobo Abe, and Toru Takemitsu, they must share their talents and experiences in their respective fields. Their chemistry will inspire each other even more: Abe Kobo's vast philosophical theory requires Echiro Kawahara to find the most matching visual metaphor, and the minimalism of Takemitsu's music prevents Echiro Kawahara overexpression. In the past, a film composer would only compose music at the director's will in post-production, but they are different. Emissary Kawara Hiroshi commented on Takemitsu: "He is more than just a composer, his figure permeates every aspect of the work - script, casting, location shooting, editing and sound design". Therefore, individual roles are not the right choice, instead they should be seen as a fluid and dynamic group. Each will offer new possibilities for the work of others. While I count these three as co-directors of their films, we shouldn't overlook the contributions of other key members. For example, the first three films were all shot by photographer Hiroshi Segawa or art director Masao Yamazaki, while the title design was done by Awazu. In fact, the three people who entrusted Hiroshi Kawahara not only made four films, it also means that they have made outstanding contributions outside their own relative fields, which means that they have created a new possibility for Japanese films. This is the most crucial part of the story.

(End of this section)

Giovanni Battista, Hiroshi Kawara, Kobo Abe and Toru Takemitsu: A Unique Collaboration in Japanese Cinema in the 1960s , Cine-scope (personal blog), https://cine-scope.com/tag/woman -in-the-dunes/ , 2013-12-28. Translated and reproduced with permission

Translated by Zhang Lei

Scan the code to sign up for the event

The International Video Culture Promotion Association (hereinafter referred to as: VCD Film Promotion Association) was officially established in Beijing in the summer of 2017. As a non-profit organization, it is committed to building a platform for viewing, learning and communication, and to popularize and promote artistic images to the public. On the one hand, the VCD Film Promotion Association provides video art education to more people by holding video exhibitions, document exhibitions, lectures and academic seminars; on the other hand, it also explores more excellent video art works through its own platform. While providing screening opportunities for them, it helps young video artists continue to create. Four Seasons Film Festival Lumen Quarterly Four Seasons Film Festival is one of the main landing projects of the VCD Film Promotion Association. It is based on the long-term and stable exhibition of high-quality artistic video works for the audience, and optimizes the audience's viewing through thematic forums, lectures, literature review, etc. experience. This film festival pays more attention to the role of personal experience in the cultural organism, and attempts to start from this, with the most open attitude, to organically combine art films, experimental films, short films, animation, video art and other types of video works. To this end, the film festival is based on the familiar timeline of spring, summer, autumn and winter. Every three months, an artist or cultural person is invited to serve as the curator, and films are selected according to the theme and screened for a long time without interruption. Through this interspersed and contrastive screening method, the VCD Film Promotion Association hopes to openly raise topics, so that the audience can have more understanding of the film and the moving image itself from a richer level and a more approachable perspective.

View more about Woman in the Dunes reviews