Introduction: Laura Mulvey is a famous British film theorist, especially famous as a feminist film critic. Her paper "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Film" published in 1975 systematically analyzed the use of classic Hollywood films as a This paper is still the key material for domestic colleges and universities to introduce feminist film criticism at the undergraduate level. But in fact, when "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Film" aroused large-scale discussions in Western academic circles in the 1970s, an important feminist question was also raised:

If the male/female in the film presents an active/passive binary, women are either degraded in erotic close-ups or punished in narratives by being convicted... then women Where is the audience's position? Where is the structural breakthrough of such binary opposition?

Laura's 1996 collection of essays, Fetish and Curiosity, was in part an attempt to answer the questions raised by her essay 20 years earlier. After separately articulating and linking Freud's and Marx's notions of "fetishes", she proposes that if the female figures in films (and films) are isomorphic to "fetishes," then perhaps "curious" ——The pleasure desire to explore and understand, rather than the pleasure desire to see/voyeur, is a way to break through the fetish structure.

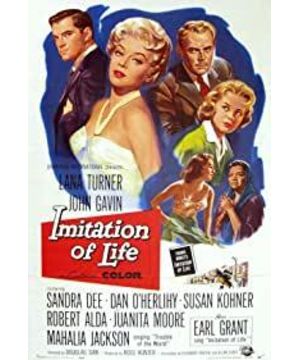

In the chapter "Social Pictographs: Reflections on Two Douglas Sirke Films", Laura analyzes Sirke's 1958 film imitation of life, through the Marxist Fetish analysis (the labor process in which a commodity engenders a fetish through its delicate appearance), opens up another viewing path for the film.

Here, I only select the part of this paper that analyzes the film and reproduce it, and delete other extensions and analysis of the 1934 version starring Claudette.

text:

[Translation] Zhong Ren

"The Imitation of Life" is not just about acting and pretense, but it also goes beyond melodrama's mournful mood to introduce issues of race, class, and so on that are often taboo in Hollywood films. The film is a melodramatic, highly emotional, and exaggerated representation of real political, social, and economic issues. Racist repression and intolerance are frequent occurrences in everyday life; everyday life is a silent realm experienced by many and without expression. Throughout the film there is a certain distance between what the audience sees and what the characters say. Only the audience can explain the relationship between the two. The tension between the decorative techniques available to white women, a false aura of protective glamour, and the revelation of black women’s essence constructs a visual discourse about race that is only possible in film.

The Imitation of Life tells the story of white actress Lola Merridith (Lana Turner) and her black maid Annie (Juanita Moore). Lana Turner played actress Lola Meredith who became the star Lana/Lola by doing the best she could. Her appearance became more and more stylized with success, so that "star status" was presented more as a modeling of appearance as a spectacle than as a social category. Lola hardly performed any professional performances. Her clothing, makeup, hair, jewelry, etc. all work together to create an image that is constructed for the camera and screen, while she may be in the story just walking around home every day. With Lana Turner's portrayal of Lola, Lola takes on an image: two star characters, fictional and real, so intertwined and so distinct that all that remains is the technique itself. However, Lola did not achieve wonder status through her own efforts. Her appearance is constructed by Annie's labor, creating a visual counterpoint to Lola's adored image.

The story begins with Lola struggling to confirm her acting status and living a life of poverty in New York with her daughter Susie. Anne's arrival was a turning point in Laura's future success. The first scene is Annie dealing with the milkman:

Later, Lola managed to get into the office of the theater agent Loomis by eloquence and get the role of "playing" a Hollywood star. When Loomis called her, her performance gained positive credibility, albeit briefly. Annie replied:

Annie's knowledge of the "servant" role and her consistent performance provided Lola with the means to succeed as an "actress." As the story progresses, Annie's performance condenses into reality. Her real behind-the-scenes work (cooking, cleaning, babysitting) turns Lola into a spectacle in a way reminiscent of workers producing goods for the market. However, the reality of their class relations has been taboo and unspoken.

In Serke's The Imitation of Life, the visible/invisible of class is determined by race. Laura's devotion to herself as a spectacle prevents her from seeing or interpreting the world around her. The film opens on a glorious Sunday afternoon of Penitence in Coney Island. As the camera turns on Lola, she is running along the plank, calling for her daughter, who has been lost in the crowd. She wears sunglasses; the camera shoots her up as if she were on stage when she was performing. In the words of steve archer, she is a "mother in grief". At the same time, he is also taking pictures of her. He raises the camera as she runs down the steps; she takes off her glasses instinctively without looking at him. Conversations that take place later, when she almost bumps into him, underscore this point. He pointed her to where the police were, just a few yards away, and she still couldn't see. But Annie found Susie.

Lola's shades and her inability to see other people run through the film like a metaphor. Her life as a star, as a commodity, surrounds her as if the light of the stage or scene blinds her. On the one hand, her work as an actress constantly separates her from her daughter, whose life is increasingly blurred for her. Another important aspect of her blindness is racial issues and the plight of Shana Jian, who manages to "perform" as white whenever possible. Lola's response to Shana Jane was, "Don't you see...it doesn't make any difference to us because we all love you." But instead, Annie sure knows it does. When she saw the social reality of discrimination, violence, and exploitation that Shana fought against, she couldn't find words to describe it. Anne's response to Shana Jian is: "Everything will be fine." From the relationship with Lola, Anne's role is a worker, an invisible labor force; from the relationship with Shana Jane, Anne is overly conspicuous . The color of her mother's skin constantly pushes Shana Jian's performances back into discriminatory social realities; if it wasn't for her mother, she would have achieved the same acting credibility as Lola.

For Shana Jian, the question of race is inevitably also a question of class; she seeks evasion or solutions outside the problem through performance. Although Lola's career as a star is respectably based on Broadway, and Shana Jian is a nightclub singer or choir member, there is a sense that Shana Jian is "impersonating" Lola. While skill and pretense on a white woman is not only acceptable but also revered, what Shana Jian is allowed to do is not live as she appears, but be sent back to a different place by society and family Visible, secret nature. She can achieve her ideal image only by denying her relationship with her mother. The question the film raises is why a society plagued by appearance and spectacle suddenly worships essence when it comes to issues of race? Shana Jian followed Lola's path to disguise and also became an actress. But she understands that disguise only works when her black mother is removed and invisible again. To gain whiteness is to gain the performance of a white woman, to be the kind of product she had seen her mother bury herself to produce. Arguably, Lola's production as a star is not just painted on the surface of Anne as her servant, but the concept of whiteness as a spectacle alienates her daughter into that spectacle-female re-performance. In one case, in the case of Shana Jian, the trace of race has been erased; in the other case, in the case of Lola, it is contained in a power relationship between workers and commodities.

In the final parting scene, both Anne and Shana Jane must play roles, with Anne playing "Mummy" and Shana Jane playing "Miss Linda". Earlier, Shana Jane showed her understanding of playing "people of color" when she served "Miss Lola and her friends." Her exaggerated parody tells the truth about race relations and the race relations that lie behind Lola and Anne's relationship. In the confrontation that follows this scene, Lola is depicted as white, not in a neutral sense, but as a person of color. Her deliberate look is visually dominated by blonde hair, off-white makeup, blue eyes, a white dress, and jewelry. This exaggeration of disguise, with the aid of an exaggeration of the representation of race, presents women as a spectacle, a spectacle of the screen. The continuous image of the white woman takes center stage and shines brightly, seemingly acting as a "blind spot," wiping out any possibility of telling the unspeakable problems that make up race in America. Anne finally gained her presence through death. In this way, when she occupies the center of the spectacle, her mise-en-scene for the funeral procession suddenly turns into a white glow. In a final, deeply pessimistic irony, however, Shana Jane is picked up back into a newly formed family: Lola, Steve, and Susie hug him in a limo. Shana Jane acquired whiteness through her mother's death.

Compared to the 1934 version, the film applies issues of camouflage and spectacle to its own production system. Metaphors about commodities and labor are more directional. Lola represents the commodity; Anne metaphorically represents the labor process veiled by the spectacle of the commodity. When the metaphor feminizes the commodity, it condenses (in Freud's sense) the invisibility of labor under capitalism with the repression of race in American society.

Lola is not an image to captivate the audience. She is great at acting reflexive, but lacks self-awareness as a point of empathy. Perhaps only Shana Jian in the film is in a position of understanding, knowing the full power of accumulating metaphors. Lola's skills are very different from Shana Jian's. Shana Jane is pushed into the show by the racism in the society around her. She was told that she was not what she seemed; she had no right to present her appearance, to take on the social status of "whiteness": it was a passport to whether or not to be "different."

View more about Imitation of Life reviews