It may be instructive to compare Eisenstein's concept of montage theory and its internal structure with that of Griffith and Pudovkin.

(Two articles, "Principles of Cinematography and Ideographs" and "The Dialectics of Cinematic Forms," on the origins of the concept of elucidation of montage, are in Cinematographic Forms)

Eisenstein saw art as a synthesis of nature and industry. Nature represents the dynamics of change and equilibrium, and industry represents purposeful and rational action on nature. The constitutive principles and aesthetic form of a work of art are the combined result of the actions of industry and reason on nature. It is this particular dialectical thought that constitutes the framework of Eisenstein's theoretical core concept, montage.

Eisenstein admits that Griffith, especially "Party to Fight Differing", played a major role in the formation of his montage concept. His later papers summarize this influence and his reworking of the Griffith montage concept.

Eisenstein, unlike Pudovkin, sees the role of montage as more than just narrative. (Difference between rhetoric and narrative)

Unlike Griffiths - giving montages is more than just comparison.

One of his remarks: The main problem of the film artist is how to take a concrete view of the world as a phenomenon. This view is determined by the revolutionary inversion of the social relations between the old and the new, and its core content is an accurate assessment of the ideological tendencies conveyed by both the old and the new. It is at this point that Eisenstein's comparison with Griffith is interesting and important.

(from an ideological point of view

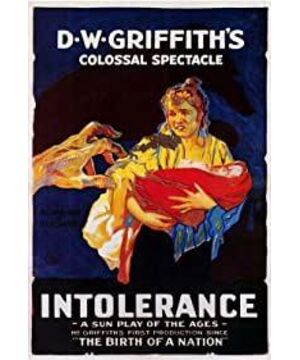

Describing Griffith's Concept of Parallel Montage: Differences from Eisenstein's Rational Montage System. Eisenstein criticized Griffith's fascination with the concept of parallel montages. Try "Party," which consists of four cross-cut stories, a narrative structure that periodically returns to the single image of the mother's cradle. The story of parallel development finally converges in an ending that is presented as a Christian miracle of some kind of dissolution and harmony. Eisenstein criticized Griffith's concept of parallel montage for its attempt to The archetypal or mystical image of the rocking cradle ties together four distinct historical stories.

This prophetic image fails to tie the four stories together, because the cradle is not enough to create a meaningful relationship between the stories. The symbolism fails to reach the heights of generalization or abstraction, it remains at the level of tedious realism. More generally, Eisenstein argues that Griffith's montage of parallels is underpinned by a false humanism: the parallels actually conflict with each other.

From "Dickens, Griffith, and Today in Cinema")

Eisenstein believed that the difference between American and Soviet films was that the parallels in American films seemed contradictory in the Soviet system. This is a difference in ideological perspective.

(Eisenstein's theory of the relationship between the artist, the work of art, and the audience/a theory from the artist's point of view: the artist is at first deeply attracted to an idea, and then quietly proposes a form to express the idea.) An idea about performance.

He also believes that the film artist must have a distinct ideological standpoint for the situations or events he depicts, and he must strengthen the performance and feelings of these events from a socially recognized ideological point of view, and strengthen the function of his rhetorical devices. The responsibility of the artist is to guide the viewer to experience and interpret the creator's point of view of the story being told hidden in the work.

View more about Intolerance reviews