https://slate.com/culture/2018/12/on-the-basis-of-sex-accuracy-rbg-biopic-fact-fiction.html

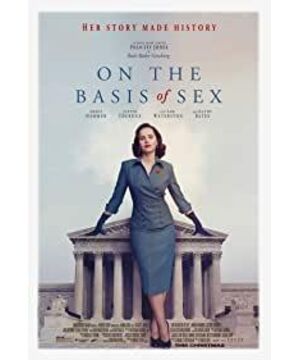

When screenwriter Daniel Stiepleman first approached Ruth Bader Ginsburg with the pitch that would become On the Basis of Sex, she had two conditions: Get the law right, and Get Marty right . Stiepleman is Ginsburg's nephew, so he knew both “Marty” (Martin Ginsburg, her late husband) and Ruth herself more intimately than most. He drew on that relationship for his depiction of the justice, who read through the first three drafts of the script before passing the task to her daughter, Jane—another prominent figure in both the legal world and the film itself.

You might worry that such an arrangement would result in an idealized portrait of Ginsburg's early years, but the creative team's go-to line during press tours has been that “ the Notorious RBG ” is “a woman, not a superhero”—and if anything , Stiepleman makes her seem a little less superhuman than she really was. Below, we break down what's fact and what's fiction.

The Harvard years

On the Basis of Sex opens with a striking shot of Ruth Bader Ginsburg (Felicity Jones) alone amid a sea of male students as the university fight song, “Ten Thousand Men of Harvard,” plays in the background. As Dean Erwin Griswold (Sam Waterston) notes in the film, she was one of just nine women in the Class of 1956. The question he poses to those women at a dinner at his home (“How do you justify taking a spot from a qualified man?”) is real and infamous—as is Ginsburg's wry response that she had come because Marty was a second-year law student, and it was important for a woman to understand her husband's work. (Did she actually believe that? " Of course not! ")

In the film, and in life, Ginsburg soon proved that she deserved her place. She qualified for the Harvard Law Review in her second year and continued to excel even as she juggled caring for her young daughter, Jane, and her husband, Marty, during his illness.

When the family relocated to New York for Marty's job, she really did go to Griswold's office to argue that she should be awarded a Harvard Law degree after she completed her final year of coursework at another university. Though she came armed with precedent, Griswold refused , and she instead graduated from Columbia at the top of her class, becoming the first woman to make both the Harvard and Columbia Law Reviews .

Marty Ginsburg

Throughout the film, Marty (Armie Hammer) holds court at parties, smooths over tense situations, and supports Ruth without question or qualification—all attributes that appear to match the real man. In Irin Carmon and Shana Knizhnik's Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg , he's described as someone who “ moved through the world with an easy confidence, tempered by an impish sense of humor .” One close friend later said that he “wooed and won [Ruth] by convincing her how much he respected her.” (And as Ginsburg tells it in the documentary RBG , the competition was fierce: In her first undergraduate semester at Cornell, with its 4:1 ratio of men to women, the young Ruth Bader “never had a repeat date.” )

We don't see that courtship happen on-screen—by the film's 1956 starting point, they had already married and had Jane, their first child—but their domestic dynamic throughout is accurate. The pair shared the responsibilities of child care, and Marty's cooking was as legendary as Ruth's was, well, notorious.

That balance was disrupted when Marty was diagnosed with testicular cancer in his third year at Harvard. While Ruth didn't physically go to his classes as she does in the film, she did collect notes from his friends and typed up his essays as he dictated them—a process that often began near midnight. When he finished around 2 am, she would turn to her own coursework. During this period, she slept just a few hours per night—but her dedication and that of their friends allowed Marty to graduate as planned, and he soon received an offer from a prestigious firm in Manhattan.

While Marty thrived in New York, where he quickly made partner and became known as one of the country's best tax lawyers , Ruth struggled to find employment at all. In the new biography Ruth Bader Ginsburg: A Life , Jane Sherron De Hart recounts how despite RBG's impeccable academic credentials, “ ethnicity, sex, and motherhood trumped other attributes ,” and these “rejections gnawed away at her sense of professional identity and competence.” As we see in the film, she eventually turned (somewhat reluctantly) to academia, becoming the second woman to teach full-time at Rutgers Law School.

Moritz v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue

Marty was also the one who first brought Charles Moritz (Chris Mulkey)'s case to her attention after stumbling upon it himself in a weekly publication of tax court rulings. Moritz was a traveling salesman who hired a nurse to help care for his elderly mother when he was away. He knew there was a tax deduction for the expense, but discovered that as a bachelor, he—unlike a woman, a widower, or a divorcé—was ineligible. In other words, by refusing to acknowledge and accommodate the possibility of an unmarried man as a caregiver, Section 214 of the Tax Code constituted sex-based discrimination. As De Hart tells it, “ When she finished reading the facts of the case, Ruth's response was just what her husband anticipated: 'Let's take it. '”

While the legal side of Moritz's case is accurate, Ruth didn't fly to Denver to meet with him. It was Marty who made first contact, and he didn't do so face to face. According to Ginsburg herself, “ We met Charles E. Moritz for the first time in the fall of 1971 , the night before the argument. He took us to dinner in Denver. He had to hire a babysitter for his mother.”

The preparation for the case was also different on both sides. For one thing, Jim Bozarth (Jack Reynor) never turned to the Pentagon for help compiling Appendix E, though another member of the Department of Justice's team did. The infamous addendum, which included every provision of the US Code that differentiated on the basis of sex, also came after their court date in Denver, when the Ginsburgs' former dean, Erwin Griswold, now US solicitor general, petitioned the court to reverse its decision. The appendix was attached to his appeal—and was, according to De Hart, “ a monumental accomplishment, because there were no computers in law offices at the time. The only way the solicitor general could have generated his list, the Ginsburgs concluded, was by using computers at the Department of Defense.”

In the film, the Ginsburgs host a “moot court” at their apartment as a trial run before the real case. Ruth lashes out in anger and stumbles when provoked, leading civil-rights lawyer Pauli Murray (Sharon Washington) to suggest that she cede half of her time to the more conciliatory Marty. But in fact, there was no moot court, and RBG never lost her cool—they had always planned to split the oral argument, with Marty handling the tax-related aspects of the case before handing it over to Ruth to discuss gender. The last-minute edits to the brief were, however, real: As Ginsburg herself explained at the film's New York premiere, her secretary at Columbia worried that the male judges would have “certain associations” with the word sex, and suggested that Ginsburg sub in the more innocuous “grammar term” gender , which she ultimately did.

At the film's climax, Ginsburg freezes up under the men's scrutiny and ends up ceding her time, only to make a last-second recovery during her rebuttal. The truth is that there was no rebuttal—Ginsburg didn't need one. Per De Hart , “ Answering every question, the novice litigator made precisely the points she had planned .” (Stiepleman has admitted to punching up the drama here. In his own words, “ Ruth Ginsburg never flubbed an argument in her life .”)

Melvin Wulf

Perhaps the greatest victim of creative license in On the Basis of Sex is American Civil Liberties Union legal director Mel Wulf (Justin Theroux), Ginsburg's childhood friend (they really did overlap at Camp Che-Na-Wah ), who becomes an avatar for the sexism she faced from other quarters. He comes off as skeptical about the need for a women's rights movement and gun-shy on taking cases that would advance it. In reality, when Ginsburg appealed to him for the ACLU's backing on the Moritz case (via a note that included a playful reference to his role in a Che-Na-Wah production of Ruddigore ), Wulf was on board in a matter of days.

On the Basis of Sex shows Ginsburg continually having to prove herself to Wulf, who insists on a mock trial for the still-untested litigator. But as established, the disastrous moot court where he calls her a “shrew” and asks if it would kill her to smile never happened. That's not to say he wasn't brash at times—he bragged that he would be the one to “ pluck her from obscurity ” and get the Rutgers law professor doing “ down and dirty women's rights work ” in front of the Supreme Court—but as he later conceded, “Maybe she plucked herself from obscurity.” In De Hart's telling, “ Wulf and Ginsburg understood each other perfectly .”

Reed v. Reed

In the film, Wulf pushes Ginsburg to write the brief for Reed v. Reed but refuses to let her present it, giving Allen Derr (Joe Cobden) the glory of arguing the first such case to reach the Supreme Court. The truth is that Ginsburg volunteered to take on the brief, and she succeeded in persuading Wulf that a woman should be the one to argue it. They settled on Eleanor Holmes Norton as the ideal candidate, but Derr refused to back down. Realizing he would be unable to take Derr off of the case, Wulf instructed him to “ make damn sure you know our brief backwards and forwards .”

Justice Harry Blackmun called Derr's attempt " perhaps the worst argued " he had ever seen, and it's fair to say that it was salvaged only by Ginsburg's writings. As De Hart puts it, " Her brief won the case, convincing the justices for the first time in the nation's history that gender-based discrimination violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. ”

Dorothy Kenyon and Pauli Murray

The brief for Reed v. Reed credits Dorothy Kenyon (played in the movie by Kathy Bates) and Pauli Murray as co-authors, despite the fact that neither woman touched it, as an acknowledgement of the way they laid the groundwork for Ginsburg's argument. The film does something similar, fudging the truth of their involvement to pay tribute to the pioneering lawyers and activists who came before her. At an event after the New York premiere, Jane Ginsburg confirmed to me that she and her mother never met with Kenyon in the run-up to the Moritz case, and Murray never came to their home to help prepare her for the oral argument—the scenes are a reflection of the fact that Ginsburg didn't start the movement singlehandedly.

After the historic wins depicted in On the Basis of Sex , Ginsburg became the director of the ACLU's Women's Rights Project and continued her campaign against gender-based discrimination. Eventually, Harvard realized it had made a mistake in denying her a law degree and tried to rectify that—a gesture she has always refused. Her rationale, as she's described it, is (mostly) borne out by what we see on-screen: “You can't rewrite history.”

View more about On the Basis of Sex reviews