Released within the same calendar year, Chilean filmmaker Sebastián Lelio’s fifth and sixth features boldly anchor their focal points onto people from marginalized spectrum and ethnic minority, and present two intimate character studies in which fortitude surmounts adversity.

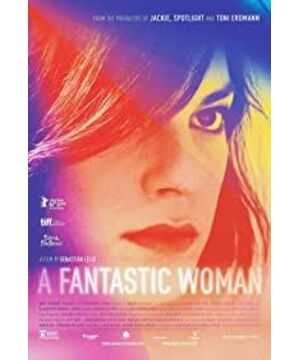

A FANTASTIC WOMAN is an Oscar’s BEST FOREIGN LANGUAGE FILM title-holder, and its title refers to Marina Vidal (Vega), a transgender woman living in Santiago, Chile, whose much elder boyfriend Orlando (Reyes), promptly succumbs to a brain aneurysm on the night of her birthday, and what follows is the standard transphobia from Orlando’s kin and common folks alike, besets her when she tries to adjust herself to the aftermath of this sudden bereavement. Lelio doesn’t hold back from the ugly repercussions when Marina is divested of her protector, common-or-garden verbal abuse escalates into physical humiliation and violence, and she has to brave it all by her lonesome.

Through Lelio’s anti-rhetoric modus operandi - for example, a Marina-versus-the-wind snapshot makes great short work of encapsulating the morass she is in - trans-actress Daniela Vega brilliantly channels Marina’s internalized baptism of fire with her dignity and integrity unscathed, it is a one-woman’s show carried on her shoulders, Vega shows immense range from resilience to fragility, through her fierce gaze, tooth-clenched restraint and androgynous pulchritude that is so distracting unique and fetching (plus her mezzo-soprano virtuoso is a sumptuous boon), not for one moment, Marina cowers before the inane hostility which marginalized people meet on a daily basis, in fact, she has no pecuniary attachment to Orlando’s next-of-kin, all she wants is to officially say goodbye to her loved one and one’s grievance swells when such a fundamental human right cannot be met with a more benevolent fashion.

Yet Lelio doesn’t launch tirades to reprimand the blinkered mind-set (because that would be too cliché and tactless), even Marina’s pent-up fit on top of an automobile doesn’t necessarily offer viewers a cathartic exhilaration, because we twig, Marina’s worst enemy is not them, they are inconsequential characters soon to be out of her life forever, the exigency is that she must condition herself to the unfair world of her own accord, “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger”, like Lelio’s bullseye-scoring metaphor pertaining to the content of Oscar’s locker (after making a striking example of Vega’s physical versatility in the strictly gender-binary sauna house), its vast emptiness is a wake-up call to anyone who pursues a lost cause or cannot let go something or someone, which or who simply doesn’t exist anymore.

DISOBEDIENCE takes place in a very different continent where klezmer and ordinances abound, but also tackles the consequences of a recent bereavement, hip New York photographer Ronit Krushka (Weisz) receives the bad tidings that her estranged father (Lesser) has passed away, which brings her back to the orthodox Jewish congregation in London after many years, where she reunites with her childhood friend Dovid Kuperman (Nivola), the chosen disciple of her father, a beloved Rabbi, who has tied the knot with Esti (McAdams), a revelation blindsides Ronit, because Esti is her former lover, and it is their sapphic affair that severed her tie with the congregation and prompted her exile years ago.

Let bygones be bygones, what a naive thought, Ronit stands out like a sore thumb in the place where she grows up, it is discomfiting to see that even today, the Jewish doctrine about the weaker sex can be still so antediluvian, the same-old platitude, getting married, having children, blah blah blah! Believe me, even in a democracy-deficient developing country like China, folks have more sense of inclusivity than this London enclave. Rachel Weisz has a field day to play the free-spirited, recalcitrant black sheep, retorts back to the elders for the sake of one-upmanship, and one may give the wrong impression she is the one who is ready to make the fur fly here.

No, it is not the case, what occasions Ronit’s unexpected return (Dovid is surprised to find Ronit at his doorstep) is Esti, who languishes in the heterosexual marriage (symbolized by her unsightly wig) and pines for Ronit’s return to rekindle her long-subdued desire, she makes the first move (catalyzed by The Cure’s LOVESONG, golden idea!) and in the post-BLUE IS THE WARMEST COLOR era, girl-on-girl sex can no longer sit back only with heavy petting coddling male gaze, so bona-fide saliva transmitting and simulated orgasm strive for the status of new norm.

More significantly, Esti is saddled with the exigent awakening to come to terms with her suppressed sexuality, from that point, Lelio’s film quietly shifts its emphasis to her, and Rachel McAdams slowly takes an upper hand in the dueling game by her wonderfully timed introspection, subtly yet compassionately achieves a well-balanced symbiosis of powerlessness (waiting for Ronit’s reciprocation and Dovid’s grant of freedom) and determination (hellbent on raising a child under a different roof of persuasion).

As a result, the story gives the final say to Dovid, a heterosexual man who has the power to free Esti or make her life miserable all at his proposal, which doesn’t seem to be jibe with a with-it feminist vogue, but Lelio is bestowed with a godsend, whose name is Alessandro Nivola, disappearing into his personage’s hardened carapace of orthodoxy, he bifurcates Dovid’s affecting modesty and sincerity into two tributaries, one toward Ronit, kind but formal, a hesitation only lingers upon his amicability, betrays his reservation, and another toward Esti, the woman he loves and marries, it is solicitious and respectful, and after being dumbfounded by Esti’s resolute coming out, he processes the whammy with extraordinary aplomb, heightened by Lelio’s attention in minute gestures, and when he unleashes that “free will” speech in the climax, it is resoundingly touching sans any soupçon of condescension, therefore, the film salvages this love-triangle tangle with a concerted effort from both genders, and a less pandering coda that is nothing if not satisfactory, thus here is an apt exclamation to Mr. Lelio “May you live a long life! (and bring us more inspiring tales)”.

referential entries: Lelio’s GLORIA (2013, 7.8/10); Sean Baker’s TANGERINE (2015, 7.3/10).

View more about A Fantastic Woman reviews