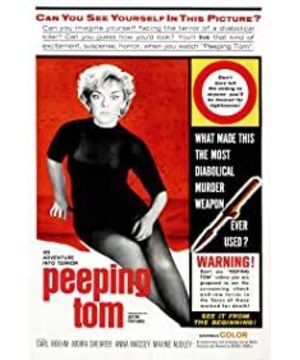

Movies make us voyeurs. We sit in the dark, watching other people's lives. This is an agreement the film made with us, although most films behave too well to not mention it. Michael Powell's Voyeur breaks the rules and crosses the line. The 1960 film tells the story of a man who filmed his victims as they were dying. When the film was first released, audiences hated it so much that it was pulled from theaters, ending the career of one of Britain's greatest directors. Why do critics and audiences hate it so much? I think it's because Voyeur doesn't allow the audience to lurk in the dark, but it ties us to the protagonist's voyeurism. Martin Scorsese once said that this film and Federico Fellini's "Eight and a Half" contains everything that can be said about the director. Whereas Fellini's films present a world full of contracts, manuscripts and acting careers, Powell's films show the director's deep psychological mechanics, especially as he gives orders to actors while standing in the shadows to observe. Scorsese is Powell's most famous admirer. As a child, he studied films made by the group "The Archers", which included director Powell and screenwriter Emric Pressburger. He frequented the midnight shows of these films, revelling in Powell's bold images and unexpected story developments. Powell and Pressberg produced some of the best and most successful films of the forties and fifties, including The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), Roger Livesey's superb Acting spanned three wars; The Red Shoes (1948), in which Moira Shearer played a ballerina; Black Narcissus (1947), by Deborah Kerr as a nun in the Himalayas; and Stairway to Heaven (1946), starring David Niven as a dead pilot. Next up is Voyeurism. This is a movie about watching. Its central role is that of a British studio focuser whose job is to tend the camera, like an acolyte at Mass. His secret life involved hiding a knife in a tripod and using a camera to photograph women, photographing their faces and looking at the negatives over and over in a darkened room when they realized their fate. He told others that he was making a "documentary". It's only in the last shot of the film that we understand that the documentary is not just about his crimes, but about his death. He did not spare himself the fate of those victims. The man named Mark Lewis was made a poor monster by his background. When the friendly girl downstairs, Helen (Anna Massey), shows interest in his work, he shows her his father's film. In some movies, Mark is a young boy who is awakened in the middle of the night by the light in his eyes. There are movies where his father throws lizards on his bed while he sleeps. Some tapes recorded his screams of fear. Mark's father, a psychologist specializing in fear, used his son to experiment. A police psychologist learned of the story and mused: "This child has his father's eyes..." Not only that. We also see little Mark next to his mother's body in the movie. Six weeks later, another film documents the father's remarriage. (The situation here is complicated: the father is played by Michael Powell himself, Mark's childhood house is the London home where Powell grew up as a child, and little Mark is played by Powell's son.) At the wedding, Mark's father gave the He has a camera as a gift. For Mark, sex, pain, fear and making movies are inextricably linked. He identifies strongly with the camera, and when Helen kisses him, his reaction is to kiss the camera lens. When a policeman handles the camera, Mark's hands and eyes restlessly reflect the policeman's movements, as if his body yearns for the camera and is at its command. When Helen was hesitating whether to wear the jewelry on her shoulders or her neckline, Mark's hand touched the same part of his body, as if he was the camera recording Helen's every move. Powell initially wanted Laurence Harvey to star, but he later decided to cast Karl Boehm Boehm). Boehm is an Austrian actor who speaks English with a slight accent that sounds more like a lack of confidence. He was blond, handsome, suave, and hesitant; Powell was intrigued to learn that the new protagonist was the son of a famous symphony conductor. He may have also experienced a domineering father. Boehm's performance creates a shy and wounded evil killer whom the film despises but also sympathizes with for his plight. He was a very lonely man, living in an apartment upstairs. The first room is average, with a table, a bed and a small area to cook. The second room was like a mad scientist's laboratory, with cameras and film equipment, a laboratory, a projection area, and indistinct equipment hanging from the ceiling. When he revealed that the house was his childhood home and that he was the owner, Helen gasped in surprise: "You? But you act like you can't pay the rent." Helen and her alcoholic and blind mother Living together (Maxine Audley), she listens to Mark's footsteps. When Helen told her mother they were going out together, she said, "I don't trust a man with such soft feet." Mark later frightened her in the inner room, and she bluntly pointed to the heart of the secret: "I have a Visit this room. Blind people always visit the room above their heads. Mark, what am I looking for?" Powell's film came out just a month before Psycho, another shocking British director . Hitchcock's film was arguably more sinister than Powell's in terms of its subject matter, but it propelled his career forward. The reason for this may be that audiences were expecting something terrifying from Hitchcock, whereas Powell hooked up more to the elegant and stylized film. Although Powell made more films, the uproar caused by "Voyeur" essentially ended his career as a director. By the late 1970s, however, Scorsese had begun to rediscover his work and supported restoration efforts, recording commentary tracks with Powell for several DVD releases. Powell and Scorsese editor Thelma Schoonmaker fell in love and got married, and she helped him write his best directorial biography together: A Life in Movies and Million Dollar Movies (A Life in Movies and Million-Dollar Movie). There's a major passage in "Voyeur" that might make even Hitchcock jealous. After a busy day at the studio, Mark persuades an extra (Moira Shearer) to stay so she can be filmed dancing. She was almost dazed by the chance to go out alone, not only dancing around a set, but even sitting inside the big blue box. The body was found in the box the next day - while Mark surreptitiously filmed the discovery. The film's visual strategy draws the audience into Mark's voyeurism. The first shot was Mark's viewfinder. Later, we see the same image in Mark's screening room, a wonderful shot looking forward from behind his head. As the camera pulls back, the image on the screen gradually zooms into a close-up, so we can see both the victim's face actually being the same size and Mark's head shrinking. In one shot, Powell shows a viewer dwarfed by the power of the film's image. Where other movies have given us voyeurism, this one costs us. Powell (1905-1990) was a director who liked rich colors, and "Voyeur" was shot in saturated colors. In one shot, for example, the victim's body is draped under a bright red blanket, standing out against the gray street. He's also a master at using the camera, and Voyeur's basic strategy is to always suggest that we're not just seeing something, but that we're always in the act of seeing. Powell's movie is a masterpiece because it doesn't keep us out of the way like those stupid teen violence movies. Instead of laughing and thinking it's none of our business, we're forced to admit that we're keeping our eyes open in fear and infatuation. (Translated by Zhou Boqun) The film's visual strategy draws the audience into Mark's voyeurism. The first shot was Mark's viewfinder. Later, we see the same image in Mark's screening room, a wonderful shot looking forward from behind his head. As the camera pulls back, the image on the screen gradually zooms into a close-up, so we can see both the victim's face actually being the same size and Mark's head shrinking. In one shot, Powell shows a viewer dwarfed by the power of the film's image. Where other movies have given us voyeurism, this one costs us. Powell (1905-1990) was a director who liked rich colors, and "Voyeur" was shot in saturated colors. In one shot, for example, the victim's body is draped under a bright red blanket, standing out against the gray street. He's also a master at using the camera, and Voyeur's basic strategy is to always suggest that we're not just seeing something, but that we're always in the act of seeing. Powell's movie is a masterpiece because it doesn't keep us out of the way like those stupid teen violence movies. Instead of laughing and thinking it's none of our business, we're forced to admit that we're keeping our eyes open in fear and infatuation. (Translated by Zhou Boqun) The film's visual strategy draws the audience into Mark's voyeurism. The first shot was Mark's viewfinder. Later, we see the same image in Mark's screening room, a wonderful shot looking forward from behind his head. As the camera pulls back, the image on the screen gradually zooms into a close-up, so we can see both the victim's face actually being the same size and Mark shrinking his head. In one shot, Powell shows a viewer dwarfed by the power of the film's image. Where other movies have given us voyeurism, this one costs us. Powell (1905-1990) was a director who liked rich colors, and "Voyeur" was shot in saturated colors. In one shot, for example, the victim's body is draped under a bright red blanket, standing out against the gray street. He's also a master at using the camera, and Voyeur's basic strategy is to always suggest that we're not just seeing something, but that we're always in the act of seeing. Powell's movie is a masterpiece because it doesn't keep us out of the way like those stupid teen violence movies. Instead of laughing and thinking it's none of our business, we're forced to admit that we're keeping our eyes open in fear and infatuation. (Translated by Zhou Boqun)

View more about Peeping Tom reviews