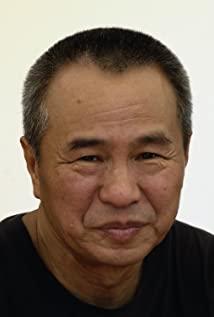

Hou Hsiao-hsien's free concept of time and space endows the film with an extraordinary sense of movement; he never has to explain the camera, and we never know the environment of Wen Qing's studio and the distance from the Zhuangzi of the Lin family, nor do we know that Wen Liang and Wen Xiong hang around. Where is the casino pub located, the two shots that are connected together are often two different spaces. In fact, this film does not explain a complete and clear spatial relationship to the audience. Hou's bold use of time was also mentioned earlier. This time-space transformation method is determined by the story of the film - a large number of characters have to be told in two and a half hours, and Hou is used to using fixed shots, which determines the inevitability of a certain degree of omission and jump; these bold transitions occur Between the slightly dull shots, it instead adds energy to the cut, making up for the lack of movement in the shots themselves. In terms of the concept of time and space, at least in this film, Hou Hsiao-hsien is similar to his Soviet counterparts, relying on the content of the camera to form a new space, but because the film has too much content, this new space is not very clear. Here is a little doubt: Did Hou Hsiao-hsien deliberately do this, to dilute the space, so that the generation of this story can become a genre in the context of a big era, and then allude to the entire era?

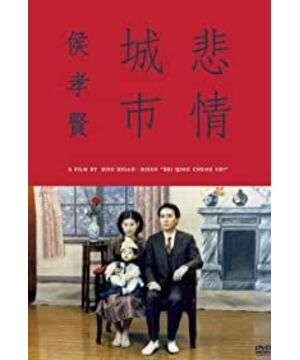

View more about A City of Sadness reviews