The film museum sits at the foot of Mount Alborz in Tehran's remote north, and if you don't want to deal with insatiable Iranian taxi drivers who don't speak English, it's better to take Line 1 and get off at the terminal Tajrish. The closer you get to Mount Alborz, Tehran's north star, and the farther away from its hustle and bustle southern center, the deeper you get into the city's middle-class neighborhoods. In the early spring of April, the top of the mountain is still covered with snow, and the smell of gasoline permeating the city has been alleviated here. The traffic congestion in the northern section seems to be relieved. The clean and modern streets are flanked by shops selling western-style household goods. , romantic cafes and exquisitely decorated pastry shops, this scene almost makes people feel like they are in Europe.

Walk along Valiasr Ave for about 15 minutes to reach the garden where the film museum is located. The main building is a mansion in the Qajar period (18th to early 20th century). Unfortunately, the film museum was not open that day, but the museum is located. The garden can be visited. All Qajar buildings, including several gardens in Shiraz, have an Islamic Baroque style, characterized by the dense symmetry of Islamic patterns and the great fusion of European-style relief lines.

In the LP's description, the film museum "is well-organized with equipment, photos and film posters representing Iran's film industry for a hundred years, with detailed descriptions." It’s a pity that I didn’t have the opportunity to visit the museum, but judging from the posters decorated around the museum, it is not a place of pilgrimage suitable for lovers of Iranian literature, art and movies, but a place for recording Iranian movies. The pavilion of development history, those literary and artistic directors who shine at international film festivals are not so respected.

On the display wall of the Movie Gallery behind the main building, I found a few familiar posters - "A Farewell", "Little Shoes" and "The Taste of Cherry" - maybe "Salesman" will be hung in the future. . According to the observation of local video stores and movie theaters, Farhadi is not only well-known internationally, but also popular domestically. His films feature the most popular actors in Iran, and the discs and posters occupy an important place. . Even on the bus returning from Isfahan to Tehran, the TV in the front row will broadcast "Salesman", which shows the degree of enthusiasm.

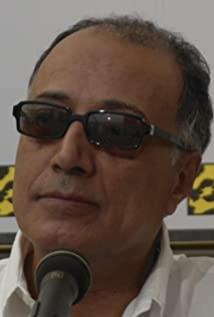

The status of Abbas seemed a bit awkward. He is still the favorite of most literary and artistic youths, and the same is true in Iran. He is rarely seen in video stores and movie theaters in the city center. But at the Artist's House, which is similar to the Artist's Activity Center, posters and ticketing information for an upcoming Abbas documentary at the Iran Art Film Festival are prominently displayed.

Every time I take a bus through the deserts of the Iranian plateau, it is most likely to think of Abbas's movies. Those rolling red and yellow mountains, dry bare barren land, and a green tree standing alone in the barren land are the most common scenes in Abbas' films. On the mountain road that twists and turns to the endless distance, it seems that those running figures in the movie, the dusty travelers and the cars that are ready to stop and chat with the passengers at any time seem to appear. The dust under the direct sunlight made the whole picture appear a warmer yellow, and my thoughts suddenly returned to the famous "The Taste of Cherry".

The first time I saw the film, I only felt that the movie was profound and obscure when it talked about suicide. When I returned from Iran to review the film, I realized that the film has nothing to do with suicide in the superficial sense. The issues it explores about human life and death are not only social, but also theological, and even more philosophical.

The story of "The Taste of Cherry" looks more like a meaningful fable. Mr Badii drove the car to find a suitable person to help him in the final steps of suicide. He planned to take sleeping pills and lie in the grave he had dug, waiting to die. Badii needs this helper to confirm his life and death the next morning. If dead, then bury him with earth. If he's still alive, then pull him up. He met soldiers, seminary monks, and museum taxidermists. When the soldier learned of his intentions, he was frightened and ran away. The seminarian was kindly persuaded that the request was contrary to his faith. Only the taxidermist complied, but he tried to convince Badii not to give up his life easily by recounting his own youthful suicide. Mr. Badii finally lay down in the tomb he had dug. At this time, the screen fell into pitch black due to thunderstorms.

There is only one really serious philosophical question, and that is suicide - Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus

The film's discussion of life and death is full of existential philosophical issues, the philosophical significance of which is that Mr. Badii's suicide is not a suicide in a social sense. Why was he determined to end his life from the start? Is it sickness, debt, unemployment, lovelorn or depression? Or a noble sacrifice for family, religion, or collective organization? From the beginning to the end, the film neither gives us a glimpse into the life of the suicidal person, nor does it provide an answer to the reasons for the suicide. The few words given by the protagonist can only reveal the state that he feels "unhappy" in life. Such secrecy makes suicide cut off from the possibility of all social connections, and becomes a pure choice of survival or not.

If it was just suicide, Mr Badii could have taken sleeping pills at home for the rest of his life, but he has no intention of doing so. He didn't want to attract too much attention, he just wanted to find someone who could confirm his death and bury him quietly. At the beginning of the film, he drives his car slowly through the market and glances at the unemployed workers who are eager to find employers. Among these people, there are many profit-seekers who are willing to do anything for money, but he does not want such a helper. He would rather run around in the city and mountains, chat with people of all kinds to understand their background, so as to find the right person in his mind - a person who really needs help.

Unlike the forced, impulsive, and depressed suicides, Mr. Badii planned his own death almost in a calm, conscious, and detached way. He went to such great lengths to create all kinds of conditions and rules for the end of his life: time, place, method, death certification and grave burial. The more detailed the conditions and forms of death, the more accurate his prediction of future fate. Before biotechnology can solve the problem of immortality, the end of human life's journey must still be death. From the point of view of existential philosophy, the future life faced by human beings is chaotic and has no goal. He only knows that the true end of life is death, and whether people realize this or not can not change this fact. After mastering the information of his own death, Mr. Badii no longer walks blindly into the future, but lives soberly and firmly towards death.

Excluding self-sacrifice, real-life suicides are mostly considered selfish because they only think about solving their own problems. However, this kind of suicide is only a recluse and escape on the physical level. Whether it is impulsive or depressed for a long time, a desperate chaotic passion is brewing. However, the physical death does not solve any problems. Mr. Badii chose to die, not incited by this chaotic passion, not to resolve contradictions individually, but to explore a possibility of existence. The fictitious personal information and reasons for suicide make this character erase his personal characteristics and social background, thus shouldering the allegorical meaning of human beings asking about their own existence. This makes his behavior more like a practical questioning ritual, thus proving that the essence of man is not a given body but a choice.

The questioning ritual of suicide is also a test of divinity

about the meaning of life. Zhou Guoping has such a philosophical quote: "Maintaining and multiplying life is human's animal nature, and seeking the meaning of life is human's divinity." In Iran in the background of The Taste of Cherry, one thing we have to consider is the deep-rooted Islamic belief of this country. The followers of Islam believe that Allah is omnipotent and omnipotent and can easily create, destroy and rectify everything that can exist. Allah is sovereign, who controls all things, and nothing can control him, he makes people live, die, rich, poor, noble, humble, his commands are not refuted. Believers should not despair because they encounter difficulties or tribulations, because despair is a loss of faith and hope in Allah, so it is a great sin.

In the Shrine of Shiraz, we were once asked about our religious beliefs by English teachers in black veils. She wondered if mosques in China also house holy mausoleums, and if people also come to pray for repentance. When told that most Chinese people are atheists, she was quite shocked: "What about your souls? What will happen to your souls after death?" Putting aside the past, I fell into a deeper myth about the Islamic view of life and death.

Abbas once said in an interview: "There is a form of freedom in the decision to commit suicide, which is the only moment we can play God or nature. Life is the sum of pain, and only this act can become a choice. We can't choose the time of birth, we can't choose the place, we can't choose our nationality, our parents, our religion, our skin color, our race. The only time when we rebel against nature or God is when We're in a time of 'Should I go on living?'. It's a violence, but with a rebellion, a challenge."

Mr. Badii, the suicidal man, was not a devout believer, and he clearly did not believe in the afterlife. The self-deceiving rhetoric that heaven goes to hell. But he is not an absolute atheist either. From the moment he had suicidal thoughts, he began to imitate the role of God, which is the suspense implied by the title "In the name of God/Allah". The choice of death is in pursuit of the absolute freedom of existence as a human being, and the process of his search for the grave burial person is both a challenge to divinity and an inquiry of God or nature. Mr. Badii did not embark on the journey of suicide with the determination to die. He left a line of opening for the continuation of his life - he asked the grave burial man to call his name on the mountain the next morning after he took the sleeping pills, if If there is a response, pull him up. Rather than saying that Mr. Badii committed suicide because he was tired of life, it is more that he hoped to attract God's attention and call upon God to listen and respond by defying the constraints of survival and reproduction.

In conversations with the young soldier, Mr Badii was an aggressive commander, trying to convince the soldier to overcome his fear of helping him kill himself with the professional nature of a soldier who has no fear of death and murder. On his way to take the monk for a ride, he turned into a witty debater, hoping to convince the untrained monk to forgive his suicide in the merciful way of God. When the old man in the museum appears, the film no longer tells the story of how Mr. Badii invited him into the car. On the way to take him to the museum, the old man deliberately chose a bumpy and tortuous road, so that he had enough time to talk about his unsuccessful suicide experience-because he was attracted by the mulberries on the tree when he was preparing the sling, which is sweet The smell of mulberries made him forget the idea of suicide for a while, and he ate one by one until the sun rose, so he gave up suicide and returned to his own life. The unpredictable appearance of the old man has an apocalyptic gesture, and the story he tells is more like a parable from a prophet. At the moment when he decided to commit suicide, he was suddenly moved by the taste of mulberries, which was inspired by nature and aroused his nostalgia and sensibility for the world. Water, sunshine, bright earth and children's playfulness are the reasons why he refuses to give up his life. Although human life has a dark death as an end, its journey can still be full of joy. The story of the old man loosened the suicidal person's firm thoughts a little, so the most emotional scene in this calm and rational film appeared: Badii found the old man again, hoping that when he confirmed whether he was dead, he would not only call him twice name, and even more throwing stones in case he just passed out. Seemingly disheartened, Badii showed reluctance to part with life for the first time at this time.

If Badii gives up suicide at this moment and the movie ends here, the exploration of survival will be limited to the meaning of praising life. Only after going through tedious and complicated procedures and listening to the teachings of the prophets, but still deciding to try death is the great and tragic part of pursuing the meaning of life. When Badii lay down peacefully in the tomb he had dug, the clouds covered with thunder, the heavy rain was coming, the picture fell into the darkness of nothingness, and transcended the antinomy of life and death. This is the moment closest to God.

Although we don't know anything about Mr. Badii's origins, the film spares no effort to show the background of the selected "passengers". Most of them are facing financial hardships and sincere at heart. Behind their seemingly simple occupational labels, they each carry a heavy family background, national affiliation and spiritual beliefs. The young soldier has a meager income, but still has to support his family. He was born in the Kurdish ethnic group without a unified country. He was immersed in the blood and cruelty of the war since he was a child. The seminary monk left his hometown in the war-torn Afghanistan to study in Iran. Although he was troubled by his troubles, he was always worried about his own country; the Turkish-born museum taxidermist was in urgent need of money because of his anemic and sick son, and sang hometown songs on the way to the museum. They are both three individuals and the intricate and intricate reality of Iranian society. The Kurds are an internal force longing for independence and freedom, Afghanistan is a mirror image of a neighboring country mired in fundamentalism, and Turkey is a possibility for secularization. The plot of the movie unfolds on the road from beginning to end, so the vehicle, the vehicle, makes the appearance of these characters on the road seem to be unconscious random, and the ingenious conversations reveal that they have been deeply affected by family, society and other people. stamped on history.

Abbas' detachment lies in the fact that he shuts out all sensual elements in presenting the suffering and poverty of these people. He didn't want to use the experiences of these people to elicit sympathy and pity from bystanders, because such strong feelings were cheap and fleeting. The old man's story about finger pain and body pain becomes an inherent metaphor for the film, and it becomes an inspiration for another viewing angle: in fact, everyone who talks to the suicidal person has not lost the courage to live, and each of them is living a life full of danger Survive it and try to rise to it, showing courage and hope. The shooting scene appears at the end of the credits, which also implies that death is not the end of life, but a symbol of the continuation of life.

View more about Taste of Cherry reviews