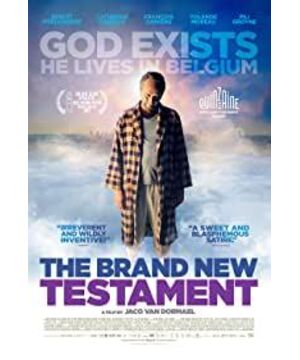

Not only does popular culture have the ability to reflect current political trends, it certainly serves as the most active and radical participant in political change. In addition to power from the state, the market also determines what ideologies can and cannot appear in popular culture (1). The Belgian comedy "Super New Testament", which was slightly popular at the beginning of the year, is an excellent text for analyzing the relationship between political trends and popular culture. The film not only reflects a part of the political ideology widely accepted in the West, but is also an effective medium for conveying a specific message and potentially affecting the audience.

Super New Testament is a new film that has received international critical acclaim, and it has also been a huge commercial success. In less than a year, the film won a string of awards and earned more than $15 million at the box office. On the surface, it's a story about God and God's wife, a disobedient daughter, and six new disciples. In this satirical story, God lives in a three-bedroom apartment in Brussels and uses a DOS-based computer to create the world. Unable to endure God's domestic violence and habit of torturing human beings, his daughter Ea escaped from the "no exit" apartment, found six disciples, and wrote a "Super New Testament". At the end of the film, God's Wife inadvertently gains the power to rule the world and creates a new set of world rules.

Undoubtedly, the film is a postmodern parody of the Bible, and it also addresses issues of religion, teenage rebellion, and more. Therefore, film critics, without exception, only pay attention to the "brain-opening" religious elements, the rebellious problems of teenagers or the problems of family relations (2). Serious religious people even regarded it as an "ungodly" and ugly work. None of these reviews have noted the unusually strong political intention behind the comedy. In fact, behind the film's softened and light-hearted form is a series of widespread feminist movements, as well as complex and fragmented gender theories. How the film uses special narrative and expressive techniques to implicitly convey this political ideology is worthy of careful study by the audience.

To dispel possible misunderstandings in the discussion, it is important to note that we cannot continue to narrowly and rigidly understand the concept of "politics" as a certain type of behavior from state institutions or powerful groups of people. In the current Eastern and Western contexts, especially in social struggles around the world, "politics" is widely understood as the exercise of power. Reason and discourse use this power to achieve specific goals (3). Such notions of "politics" abound in everyday discourse, such as the "office politics" of factional struggles, the "race politics" between racists and anti-racists, etc. These forms of social struggle are all applications of a specific power, and they are generally regarded as serious political texts by contemporary political researchers (4). Therefore, this article will not repeat the connection between concepts such as “political consciousness” and “feminism” mentioned above.

anti-patriarchy themes

Super New Testament is first and foremost a film critique of traditional patriarchy and male hegemony, and it conveys that intent in a pop comedy way. In the film, God is portrayed as a life-weary loser, a conceited tyrant. The story tells the audience that the disasters, wars and chaotic order of the human world are all the work of a grumpy man who takes pleasure in harming innocent human beings. The character is also the father figure in a conservative family, always a hilarious appearance, wearing a scruffy nightgown, socks and slippers, yet he creates this kind of "humanity" so that people fight each other . At the same time, he also created a series of "laws" in order to bring trouble to mankind. Ironically, when God first came to the world, he was abused by this "human nature" and suffered from "laws": when he was looking for hamburgers in the trash can, he was beaten and scolded by a group of hooligans; While robbing a little girl of bread, the bread, according to the "rule" jam-side-first-god, comically becomes a victim of his own world. This plot arrangement can be seen as an indictment of the cult of phallic power, which is directly the source of chaos and conflict in the existing world, which is dominated by men. At the same time, the plot implies that both men and women are actually victims of this patriarchal system.

On the other hand, there is a stark contrast between this tyrannical authority in the image of God and the successful rebellion of the daughter Iya, which symbolizes hegemonic paternity and masculinity in family and public life. of disintegration. The protagonist was initially set up in an enclosed space "with a fully equipped kitchen and laundry" and an "office that no one can enter except God." She has been trapped here since birth, and there is no "entrance or exit" to this place. This setting of the film fits right in with the thinking of the second wave of feminism in the 1960s, which believed that "the family is the source of the oppression of women" (5). This exaggerated form of the "nuclear family" seems to imply women's place in a traditional patriarchal environment: they are often tethered to this enclosed space from birth, and family life is viewed do their vocation. How to escape this traditional cultural arrangement is the main issue discussed in this comedy. On this theoretical basis, the film is a metaphor for the collapse of the patriarchal system and the redefinition of women's status. The film ends by showing the audience a world with new orders that it believes are good for the world, and that the establishment of this new order should begin with the rebellion and independence of women.

A new image of feminism

To show this rebellious spirit, the film also portrays women in an unconventional way, based on the feminism that is currently widespread in the West. In this regard, films are very different from other popular audiovisual products.

The rebellious female image has a long history in the film and television media, and these images have also undergone a dramatic transformation in the past few decades: women have become increasingly independent on the screen, and they are part of the storyline. The weight is also getting heavier. It is hard to deny that most of these characters share very similar traits: they start out as vulnerable women seeking independence, self-confidence, and success in a male-dominated society, but are always confronted with impossibility in one way or another. Therefore, in the end, the crisis will be resolved by compromising or seeking protection (6). In some commercially successful films, such as "Silly Girl Joins the Army" (Private Benjamin, 1980), "Die Hard" (1988), "What Women Want" (2000), etc., In the end, "rebellious female characters" could not achieve the ideal social status. In this setting of characters and plots, women's "vulnerabilities" naturally become a contrasting material, in order to highlight the capabilities and dominance of men.

At the same time, women are often portrayed as tougher in popular films. They are portrayed as heroic characters with strong masculinity and violent personalities. These new screen images are often associated with violence, hegemony, etc., and are seen as a reflection of the feminist ideological trend at the time (7), these women's personalities are either dominated by revenge complex or anger, or come from Intense desire for material things (8). We can find this type of image in a range of popular action movies or dramas. For example, Thelma and Louise (1991), Tomorrow Never Die (1997), The Matrix I (The Matrix, 1999), the X-Men series (X-Men) , 2000-2016), heroines can directly participate in violent conflicts and fighting performances. However, these female figures share the same characteristics: they all have seductive bodies—beautiful looks, sexy dresses, and, at the same time, they can exercise strong male hegemony in a patriarchal system. Underlying these images of women is the dissolution of gender boundaries—they need to be both beautiful and good at fighting (9).

In portraying the new female image, "Super New Testament" shows the audience a different way. The image of the protagonist is neither a person in need of protection nor a person who advocates male violence. She rebels (rebels) against the patriarchal system in which she lives in a new way: by breaking into her father's office first. In this office, God decides the fate of all human beings and prohibits others from entering. This prohibition actually implies the position of women in public affairs, a political tradition that has been in place since Plato's time. In the Meno, Plato wrote: "The virtue of a man is to manage public affairs, and the virtue of a woman is to take care of the family" (10). Clearly, Iya's slip into God's office was itself a highly political sign: women began to meddle in public affairs.

In addition, the protagonist also creates a new image by escaping from patriarchal rule and seeking independence. Yiya escaped through a secret passage in the washing machine, and this arrangement reflects the important details of the feminist trend of thought. It is necessary to note that this trend of thought began to challenge the traditional boundary between "public life" and "private life" after the 1960s, and they put forward the slogan "the personal is political" ( 11). This elimination of the private-public boundary is particularly important in the ensuing struggles over race and gender identity. The performances and props of the washing machine are deeply symbolic - through the tools of domestic life, a repressed girl finds a way to public life and free choice. Furthermore, following Beauvoir, feminists also began to question existing structures of order that did not fit their way of experience (12). This part of the school of thought believes that issues that were previously considered to be in private life, such as domestic violence, child rearing, family allowances, etc., should be given attention in the public sphere (13). For Eya in the film, fleeing from the family is not just a break from a brutal patriarchy, it also brings the struggles of private life into the public sphere.

Reaffirmation of Femininity and Fourth Wave Feminism

Besides Ijah, another notable image is Ijah's mother, God's wife. It's a deeply repressed female character, but also a silent, sympathetic and trembling figure with a very conservative housewife style. The character has undergone a dramatic transformation, and she is also an enlightened and awakened female figure. After God's exile, she decorated the apartment with colorful hand-woven blankets and beautiful music, turning the residence into a warm and gratifying place. In addition, she has the ability to reset computer systems and turn the world into a harmonious, colorful and joyful whole. From a political point of view, at least two trends in feminism are included in the setting of this image.

The first trend is re-acknowledgement of femininity. After the 1980s, feminists began to reflect on the previous wave of calls for "gendered sameness," which had been raised to eliminate gender inequality. The reaffirmation of femininity, on the other hand, critiques traditional male-female dualism, a trend that instead emphasizes the difference between masculinity and femininity (14). Both masculine femininity and feminine masculinity are in fact ignoring the differences between nature and gender (15). She (he) argues that the existing world order needs to seek new paths to change, rather than requiring women to seek any neutral claims, both physically and psychologically (16). In popular culture, however, female images of graceful stature, villainy, and tough-guy temperament are essentially emphasizing the old idea that masculinity is the characteristic that can be established (17). In the Super New Testament, however, the image of the Goddess offers options for a new kind of ideal society—a world that can be full of femininity, not dominated by feminine masculinity. In the new world, masculinity and femininity are treated with equal respect, and it boldly assumes that femininity brings happiness to the human world.

The Goddess's use of computers to connect with and change the world is also a profound symbol. At the end of the comedy, the goddess resets the computer system and rearranges the order of the world, and the sky becomes colorful and the color temperature of the picture changes from dull cool to bright warm. The music she played at home also appeared in the beach scene as a diegetic sound, and the whole world knew of the Goddess. This highly romantic scene setting and performance is not only a fantasy in a comedy, but also a metaphor for the current trend of feminism. In fourth-wave feminism, technology and the Internet are considered indispensable and important forces (18), and some young feminists believe that women should use the Internet as a tool for a campaign, in order to expand their audience. If in the home of the Goddess, the new decor and atmosphere symbolize that women are beginning to express their voices in domestic life, then the shifting of the sky, the romantic laws of nature, etc., symbolize the use of technology by women to publicly declare their demands. They believe that even women at home, through the use of modern technology, have the discourse power to enter the public sphere, express their voices and change reality.

Explanation of Feminist Linguistic Theory

In terms of performance style, the film uses a unique image language to describe feminist ideas and trends. In the late 20th century, a group of people known as "radical women" proposed that the current language system is actually the source and tool of oppression and alienation of women. They believe that this linguistic structure has continued to reproduce women's marginal status. Represented by the ideas of Mary Daly and Adrienne Rich, this trend builds theoretical foundations on the sociological ideas of Peter Berger. Berg believes that human society as a whole is a "word-building enterprise" in which language is the basic norm by which members construct all meaning (19). Radical feminists thus argue that the existing body of knowledge is in fact entirely based on and manipulated by male hegemonic power (20). However, this system of meaning forces women to use existing discourse systems to narrate and express experiences that are completely different from men's (21). Therefore, they propose that a whole new language system should be invented to re-express and think about the world, so as to avoid and escape from this "male hegemonic culture" (22).

To tell the story, the Super New Testament uses a unique set of stylish techniques that are very different from conventional rhetorical devices. First, the film visualizes the "new language system" that makes possible a universal system of writing and recording. The old tramp Victor, the author of the "Super New Testament" in the film, did not use any letters or existing language symbols, but "written" the work by using a series of stick figures . In the film, the "Super New Testament" as a new knowledge system has also been recognized by the public. This arrangement of props can be seen as a subversion of the old language system, which was based on the recognition of male hegemony.

In addition, the film expresses new linguistic theories by visualizing metaphors. For example, when the narrator compares Aurélie's laughing statement to "like pearls strewn on a marble stair," the simile is rendered in slow motion as hundreds of pearls fall on the marble stair; When the voice of a homeless person is likened to "three hundred people breaking walnuts at the same time", the picture of a group of people sitting in front of a long table with walnuts appears. In Western linguistic thought, since Aristotle, metaphors have been regarded as irrational, pretentious and deceptive rhetorical techniques (23). However, feminists, represented by Richie, suggested that the use of metaphors can open up a new world for expressing realistic feelings (24). In part of feminist language thought, metaphor is regarded as a means of struggle. It has always existed in the patriarchal knowledge system as uneasiness. It can better express the emotions in reality. have been ignored by the tradition of rational narrative (25). In addition to this, the film uses other tropes to describe the feelings of the female character, such as "his skin is like an old viper waiting for a cup of blood in an abandoned bar". This amplification and visualisation of metaphors actually expresses feminism's language appeal in an entertaining way.

Epilogue (not really meant to be)

as a successful comedy, Super New Testament actually reflects and narrates the current wide-ranging movement and struggle for women's rights. The above discussion reveals the dynamic interrelationship between popular culture and politics. It needs to be emphasized again that in the current context, the concept of "politics" is usually about the behavior and process of rights and distribution of power, which is guided by a specific political ideology behind it. Feminist thoughts and demands are undoubtedly the ideology behind a certain political struggle.

----------------------------------------

Citations

(1) Barker, CE Media, Markets and Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. Print. p120.

(2) See: Brown, Hannah. “'The Brand New Testament' is A Divine Comedy.” The Jerusalem Post. 31 December, 2015. Web. 28 April, 2016;

Kiang, Jessica. Karlovy Vary Review: “'The Brand New Testament' with Catherine Deneuve Gently Blasphemes with Wit and Style." The Playlist. 15 July, 2015. Web. 28 April , 2016;

Young, Deborah. “'The Brand New Testament': Cannes Review.” The Hollywood Report. 18 May, 2015. Web. 28 April, 2016.

(3) Arneil, Barbara. Politics & Feminism. Oxford, UK; Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 1999. Print. p2.

(4) Kellner, Douglas. Media Culture: Cultural Studies, Identity, and Politics between the Modern and the Postmodern. London; New York: Routledge, 1995. Print. p58.

(5) Hollows, Joanne. Feminism, Femininity, and Popular Culture. New York: Manchester University Press, 2000. Print. p4.

(6) Glitre, Kathrina. “Nancy Meyers and 'Popular Feminism'.” Ed. Waters, Melanie. Women on Screen: Feminism and Femininity in Visual Culture. Basingstoke ; New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. Print. p19-23.

(7) Hinds, Hilary, and Jackie Stacey. “Imaging Feminism, Imaging Femininity: The Bra-Burner, Diana, and the Woman Who Kills.” Feminist Media Studies 1.2 (2001): 153-77. Print. p168.

(8) Hopkins, Susan. Girl Heroes: The New Force in Popular Culture. Annandale, NSW: Pluto Press, 2002. Print. p6.

(9) Ibid. p116-118.

(10) Plato. Meno: A Dialogue on the Nature and Meaning of Education. New York: Harvard University. 20 June, 2006. Web. p158.

(11) Arneil, Barbara. Politics & Feminism. Oxford, UK; Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 1999. Print. p44-46; 76; 164.

(12) Hollows, Joanne. Feminism, Femininity, and Popular Culture. New York: Manchester University Press, 2000. Print . p5.

(13) Arneil, Barbara. Politics & Feminism. Oxford, UK; Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 1999. Print. p164.

(14) Ibid. p195.

(15) Ibid. p196.

(16) Felski, Rita. Doing Time: Feminist Theory and Postmodern Culture. New York: New York University Press, 2000. Print. p119.

(17) Hollows, Joanne. Feminism, Femininity, and Popular Culture. New York: Manchester University Press, 2000. Print. p194.

(18) Munro, Ealasaid. “Feminism: A Fourth Wave?” Political Insight 4.2 (2013): 22-25. SAGE. Web. p23.

(19) Berger, Peter L.. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. Trans. Luckmann, Thomas. London: Penguin, 1991. Print. p20.

( 20) Arneil, Barbara. Politics & Feminism. Oxford, UK; Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 1999. Print. p183;

Cameron, Deborah. Feminism and Linguistic Theory. Second Edition. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1992. Print. p130;

Hedley , Jane. "Surviving to Speak New Language: Mary Daly and Adrienne Rich." Hypatia: A Journal of Feminist Philosophy 7.2 (1992): 40-62. MLA International Bibliography. Web. p104.

(21) Cameron, Deborah. Feminism and Linguistic Theory. Second Edition. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1992. Print. p141.

(22) Arneil, Barbara. Politics & Feminism. Oxford, UK; Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 1999. Print .

p183 ; Munro, Ealasaid. “Feminism: A Fourth Wave?” Political Insight 4.2 (2013): 22-25. SAGE. Web. p25.

(23) Janusz, Sharon. “Feminism and Metaphor: Friend, Foe, Force? ” Metaphor and Symbolic Activity 9.4 (1994): 289-300. Web. p292-293.

(24) ibid. p296.

(25) ibid. p299.

View more about The Brand New Testament reviews