The emergence of the Romanian New Wave seems to be in Eastern Europe, a continuation of the Czech New Wave of the 1960s. Most of these Romanian films are realistic, with less soundtrack and more long shots. Of course, it is developing, and its richness has not been fully revealed; there are many satirical dramas in the Czech New Wave that are extremely mocking, exaggerated and deformed, with strong personalities. Documentary, there are also typical European art films. They have one thing in common, they are all connected to the system. The ever-changing Eastern Europe used its ill-fated fate to give birth to these works. Herta Müller, winner of the 2009 Nobel Prize in Literature, a German female writer, was born in Romania. No matter how poetic and other artistic features of her works are, almost all of her works are political allegories, which is the more dazzling feature. The most meaningful life for her, she said, was her experience under Romania's totalitarian rule. Look, when these dazzling directors and writers receive various trophies, they all have to say: "Thank you to the country." Only when they encounter history and system will they be full of talents, or they must rely on those events to hatch the eggs of literature and art. The same is true in Latin America. Llosa used his fancy structure to decorate the absurd reality. It is not so much that he created the Einstein of the pimp world ("Captain Panda Leon and the Labor Girl"), but that the system gave Llosa a lovely captain.

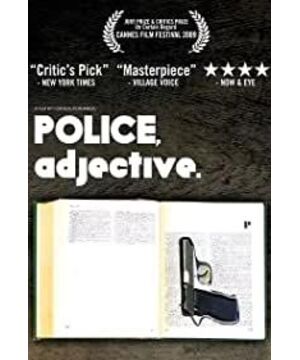

Let's take a look at how closely these Romanian films are connected with reality and with the system. The 12:08 in "Bucharest East 12:08" refers to the dictator Ceausescu on December 22, 1989 at 12:08, Escape from the presidential palace is a significant historical node for Romanians; the allegory of "California Dream" directly points to the United States, which is very absurd and sharp; the abortion involved in "Three Weeks in April" is related to the Romanian legal system; "Police, adjective" is related to the police system statute, more to the system as a whole; and so on.

The plot of "Police, Adjectives" is extremely simple. A police officer is unwilling to obey his boss to arrest a student for smoking marijuana, because in his opinion, this is something that his conscience does not allow. The style of the film is stern, emotional restraint, natural lyricism is absent, and satire is also restrained, like a cold joke told by an extremely serious person, suppressing, hiding, and even not ready to show it at the end. Constable Chris is adamant that the law will change and is reluctant to punish children who make minor mistakes as they would in other countries. The boss used dialectics to decree that he obeyed, and his conscience did not carry the decrees and orders in the end.

Chris's boss is an institutionalized person, and must be an old man from the Republic era. He is the personification of the old system. Some of the details in the film are meaningful. The computer in Chris's office appears several times, very conspicuous at the top right of the screen, but never turned on. It is still an old-fashioned monitor, in stark contrast to the LCD monitor in Chris's home. The reform of the Romanian police system is clearly behind people's lives. The long shot of Chris waiting in the office, and going to various departments to find information, obviously means that the old system is still extending.

All viewpoints start from Chris, who is also the embodiment of a pair of contradictions. He believes in the reform of the system, but abides by his conscience. Of course, it is not that modern civilization rejects morality. His avant-garde views and conscience can also be seen as complementary words and deeds. In the past, whistleblowers were prevalent and morality almost collapsed. The only real morality was the system itself. What Chris lacks in expression and body language is not simple, he is a common and wonderfully materialized image.

Build details with very realistic long shots that are so close to reality, it's almost like replicating a real scene. At the same time, it seems to be far away from reality. The minimalist story is like a fable. The fixed long lens maintains an objective appearance and presents an abstract quality. Natural and smooth coherent editing makes the film concise and powerful. A long lens makes you aware of the camera, just like in reality, sometimes you realize you're paying attention to an object, but you're still focused. It's a little distracting, but not distracting.

Will the vitality of this kind of film nurtured by the system/reality/time be shorter than that of a film that is art for art's sake and starts from human nature that has nothing to do with the times? Many of the Czech films with strong "timeliness" in the past have been forgotten. If the images based on the subject matter do not have a significant style and breakthrough, they may be forgotten when the popularity of the subject matter and the time-sensitive function disappear. Márquez's "One Hundred Years of Solitude" will be more widely and longer than Llosa's "Captain Panda Leon and the Girl in the Army"? You can say that "One Hundred Years of Solitude" has higher artistic attainments. Besides, will the conspicuous structure of "The Captain and the Girl" be dragged down by its "outdated themes" a few years later?

A film like "Police, Adjective" is consuming the past history and the current status quo. It can also be said that the director is digesting the history of the nation and the country, recording an era, and it is a film of conscience. After using up these resources (assuming they can be used up), will his talents and abilities suddenly shrink? In addition to a conscience that has not been institutionalized, he can also move the camera a little closer to reveal the image of people, and is no longer a symbol that is completely attached to the society. The pursuit of lens art and the era of satire has transitioned to the pursuit of the lens. Art and deep humanity.

View more about Police, Adjective reviews