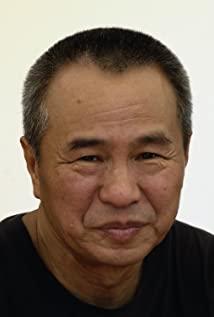

If the South is frozen, then the thought in my head will become a truth and wrap the entire planet. But Hou Hsiao-hsien tried his best to destroy my original stubborn thoughts. He broke the silkworm cocoon that was about to take shape. He sang another possibility of the epic in his own way-simple, stingy, and tragic...

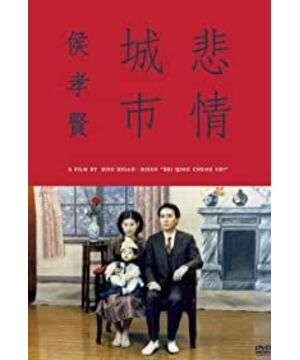

"City of Sadness" in a sense marks the beginning of Hou Hsiao-hsien's second conscious creation, but this subversion Obviously not as thorough as the last "The Man from the Windbox", this is a kind of reform hidden under the current, he steals his identity from a leisurely ballad singer in the fields to a slow-paced bard . If, like me, you are accustomed to looking at Hou Hsiao-hsien and his works from an inverted perspective, such as the fleeting melody at the end of every movie, you will find that the music hides the most subtle of his thoughts. Variety. Bach's "Aria on the G String", the last chapter of "The Man from the Windbox", is about the youth where poetry and frustration coexist. The simple guitar at the end of "Love in the Wind and Dust" plucked an ethereal "Ship of Time", saying To do a period of inseparable love and sorrow. His favorite music is just like the stories in his mouth, tasteless and bland. Hou Hsiao-hsien before "City of Sadness" was "stingy". The only thing he can do and do is a never-ending narrative—a dry, bland, dry narrative that lacks moisture. He loves to tell stories, but it's a little funny that he's not a lyrical man, and the language he speaks always makes him at odds with his own vision. He's a bit clumsy, he won't add oil and vinegar, and he won't arbitrarily use exaggerated contrasts and parallel parallels to decorate his stories with these condiments that others see at their fingertips. He looked like an old man, his wrinkled skin was unsightly. Maybe more like an old tree, the bony kind.

But old trees also bloom. So when this man suddenly became so excited, you had to feel a little bit of surprise--the music adapted from Japanese Noh music at the end of "City of Sadness" lets you see an unprecedentedly heavy Hou Hsiao-hsien. This time, he slowly opened a vermilion door, then picked up the baby called History on the ground and put it on his back, and started a difficult walk without looking back, which lasted six years.

No one wants to write an epic about modern times for Taiwan. People prefer to use sympathy, grief, or hatred to look at this beautifully curved, lustful, yet devastated body. His hands were tightly bound in his pockets, intentionally or unintentionally. They were never that lifesaving doctor. In the end, the dying patient was left alone to move forward. I have imagined the appearance of the rescue hero countless times. Maybe he should act like the Hu Defu who has been singing and fighting all his life with music, but in the end, it is the somewhat ingenious Hou Hsiao-hsien who bears that responsibility.

Forgot to tell you, I always feel that one of the three "H" in this man's name (Hou Hsiao-Hsien's English name is HOU HSIAO HSIEN) will eventually become attached to "HOMETOWN". Before "City of Sadness", he had always been inseparable from the fetters of "hometown", "People from the Wind Cabinet" was about leaving home, "Dongdong Holiday" was nostalgia, and when "My Childhood" came, it became nostalgic again . Finally, Hou Hsiao-hsien seems to be no longer constrained by the limited landscape. He wants to sing about history and write about the past, but the most mellow "hometown" love in his bones can never be given up. He writes epics, but a small family has become a big family. He chooses to set sail from a small point to make a big history. He expresses a big emotion, but in the final analysis, it is a collage of countless trivial small emotions. His epic is just a combination of ballads, and his atmosphere is actually a stack of petty feelings. The epic of the southern country is so plain.

The topic of life and death has always been a favorite of Hou Hsiao-hsien, and the faint pathos in his works mostly stems from his almost indifferent account of death. The death of Aqing's father in "The Man from the Windbox", and the death of Ahagu's father, mother and grandmother, the protagonist in "Once Upon a Time in Childhood", are all like this. But these "deaths" are extremely simple, as if they only refer to time and remember some obvious images. And his obsession with death was brought to an extreme in "Sad City". I will remember the very poetic English name of "My Childhood" - "THE TIME TO LIVE AND THE TIME TO DIE". Since Hou Hsiao-hsien wants to tell a tragic story, it is better to give up "birth" altogether, from beginning to end. Tell you all about "death". "Sadness" in "City of Sadness" can be drawn as an equal sign with "death". The film begins with the birth of Lin Wenxiong's first son and the Japanese defeat of Taiwan's liberation, but this does not herald any light or hope. Hou Hsiao-hsien straight-up presents a perfect object in front of your eyes, and then he does It is a kind of slaughtering subtraction, so that each life is directly or indirectly ended in the story. He made the whereabouts of Principal Xiaochuan unknown, the gangster Red Monkey was betrayed by his mistress for no apparent reason, and the woman cried when she saw her husband's last letter. Death or disappearance is suddenly elevated to an unprecedented level in this film. But death is only an external manifestation after all, a visual symbol, what it hides should be more of a loss of self-control of destiny and the subsequent feeling of powerlessness. This sense of powerlessness should not be limited to individuals, it should be a spreading virus, spreading in this sad city and on this sad island.

I don't like to easily attribute "City of Sadness" to a tragedy. Even though Hou Hsiao-hsien's iconic documentary style and objective and cold camera language are closer to Western-style sentiment over the years, I believe he is still oriental in his bones. . What he narrates is more like an epic soaked in grief, but not tragic. The so-called "sorrow" was engraved in Hou Hsiao-hsien's poetic narrative language. This kind of "sorrow" is not the long-standing tradition of tragedy in the West - the tragedy of character or fate, but the helplessness in the face of order and rhythm. . The East never had the three goddesses who mastered the thread of destiny. In Chen Qixiang's words, "destiny is often an image of a blank time and space, a huge and boundless flowing rhythm, without personal will and irresistible." Only poetry can grasp it. This invisible flow exudes a feeling of fragility, powerlessness, or longevity. In "City of Sadness", almost all "deaths" reflect such a destined helplessness, especially as the protagonists of this epic, the four brothers of the Lin family and Wenqing's friend Kuanrong.

Hou Hsiao-hsien divides the protagonists of the story into different clues to express, and each of these paths leads to a different tragic ending. The eldest brother Wenxiong represented a kind of Taiwanese native force, and he finally died in the gang fire and died in the "Ashan" (Taiwanese name for foreigners) the hands of the Shanghai Gang, which seems to be Taiwan's native culture. Frustrated in the collision with the migratory culture of the mainland. The second brother never officially appeared in the movie, only mentioned in Kuanmei's self-reported diary and Wenqing's note, but it is an indisputable fact that as a Japanese mercenary, he was far superior to his death in a foreign land in Nanyang. Human harm, needless to say. Although the third brother Wenliang was spared the first death, the two madness made him seem more distressing than the simple death. After the Restoration, the Nationalist government purged the traitors. Wenliang's fate is more like a precarious depiction of modern Taiwanese. The mania that he showed at the first onset can still make people experience the original explosive force and rebelliousness of life, but after being arrested as a traitor and released from prison, he turned into a completely lost vitality. Living by eating food sacrificed to ancestors eats away morals and devours souls. This alternative loss of life stems from the unfortunate overlap of two eras. Kuan Rong is an exception. He symbolizes a kind of intellectuals' resistance to the established order and destiny, but he still failed in the end. In the face of history, he is powerless. As for the lovers of Wen Qing and Kuan Mei, they are more like the most common people in Taiwan. In the face of multiple conflicts and complex historical and cultural backgrounds, it is difficult for them to obtain the right to communicate directly with the outside world. In the film, even the most ordinary communication, they even have to use Taiwanese-Cantonese-Shanghai dialect, which is full of twists and turns. The estrangement, misunderstanding and prejudice have made the entire Taiwanese people as silent as Wen Qing, suffering from collective aphasia, becoming dumb and deaf, falling into the darkness and silence for a long time, and bearing the pain of tragic. As Kuan Mei finally wrote in her diary, "Escape, where can you escape to?" In a sad city, neither silence nor escape can redeem oneself.

All tragedies point to different contradictions, but the deeper level of these contradictions should also point to an oriental concept of destiny, a helplessness in the face of the passage of time and space and the inherent order and rhythm, an inability to grasp the fate and The sense of loss caused by this, and the extreme manifestation of the sense of loss, is death. The misfortune of all the characters in this story stems from the untimely birth, and even the tragic sorrow of the entire modern Taiwanese nation can be attributed to the untimely birth. If there is no "Treaty of Shimonoseki", if there is no Anti-Japanese War and Restoration, if there is no "228 Incident", if there is no... But no one can choose or rebuild a disordered time and space. History has placed modern Taiwanese in such an existence And they did not challenge the order like Kuafu Chasing the Sun or Yugong Yishan, rushing out of the net to stage a comedy. Their "self-consciousness" to a certain extent makes them helpless in the face of fate, and they have thus achieved a tragic southern epic.

Hou Hsiao-hsien is not good at and doesn't like sensationalism, so the "feeling" in "City of Sadness" is more like his own personal feelings for the big ethnic group in Taiwan or his thinking about history. There is no need to say much about Taiwan's unbearable past, but Hou Hsiao-hsien is more interested in the fluctuations of Taiwanese's inner emotions, which may be the "emotion" he wants to pursue. In the order constructed by many coincidences and destiny, Taiwanese are placed in a very awkward position on the stage of history, which determines that their emotions towards the outside world are complicated. This love-hate emotional end connects two faces - the mainland and the Japanese. The attitude of the Japanese as an aggressor marked Taiwan with pain and bullying, but one must face up to the fact that Taiwan under Japanese rule established an industrial system that was far superior to that of any province in the mainland at that time. But it was still a slave life. Although the resentment of Taiwanese in modern times towards mainlanders is unavoidable, after all, they cannot bear the shame of being betrayed by their own compatriots. Are people willing?" But at the beginning of the Restoration, the Taiwanese welcomed the mainlanders from the bottom of their hearts, but what they welcomed was a group of stragglers far inferior to the Japanese army, and what they were waiting for was unprecedented soaring prices , the White Terror and the more brutal "228 Incident". The illusions of Taiwanese people are shattered again and again after repeated expectations. Their emotions cannot be accepted by any party. They can't even find a sense of self-identity, like a homeless child, described in a line by Wen Xiong. "We are the most pitiful people on this island, the Japanese, the Chinese, everyone rides, everyone steps on, and no one hurts." Hou Hsiao-hsien didn't want to deliberately accuse the mainlanders or the Japanese, he just tried his best to To restore the damage caused by history to the ethnic groups in Taiwan and to show the activities and moods of people in that era under the laws of nature. Even the "February 28 Incident", which may cause a lot of controversy in the imagination of many people, still follows his usual bland style without any fluctuations or shocks. As a prospective native of the island, he certainly could not accept the bloody and terrifying era of the Nationalist government, but he also opposed the rejection and attack of "Ashan" by the natives of the island. Hou Hsiao-hsien tends to be emotionally neutral, a pure soulful gaze, a record of the complete flow of time.

"In December 1949, the mainland was changed. The Nationalist government moved to Taiwan and designated the temporary capital, Taipei." When the subtitles appeared along with the sad melody with the unique humid atmosphere of the island, Hou Hsiao-hsien's Southern Kingdom The epic has finally come to an end. But the tired port is still dense, still shrouded in endless chaos. Therefore, people go to see the next time-space flow performance together, and then listen to another southern epic about themselves.

But it's always so plain, natural, maybe with a little sadness...

View more about A City of Sadness reviews