I have never concealed my contempt for Huo Qubing.

He said that the Huns were not destroyed, and they had nothing to do with their families. Indeed, he did it—drinking the horse Hanhai, sealing the wolf to the throne, and in a weak year, he achieved something that few generals in the past and present can achieve.

But does this feat really belong to him? We can't pretend we can't see the skeletons of his soldiers behind him.

So, how does he treat these soldiers who travel thousands of miles with him? "Records of the Grand Historian" mentions a few lines: "...heavy chariots abandon the grain and meat, and the soldiers are hungry. They are outside the fortress, their soldiers lack food, or they can't stand up, while the hussars still pass through the territory and cuju. There are so many things like this. ."

The ruthlessness of people, and so on.

But here, I do not want to discuss the neglect of the masses by history books. I would like to talk about some unprovoked associations after watching the movie.

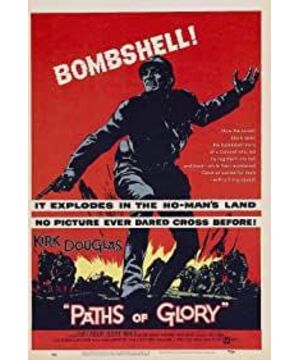

The "Road to Glory" mentioned in this work seems to refer to the execution road set up to rectify military discipline and strengthen the army in the eyes of the general. This is an obvious shameless act.

From another perspective, is it glorious for soldiers to die on the battlefield? How could he tell whether his sacrifice was a romantic death for his country, or a "small" mistake by his commander? Second, why did he die and not someone who eventually survived? I don't understand whether this uncertainty and contingency of sacrifice is part of "honor" or part of dark humor?

Taking a step back, even if he voluntarily died for the country under a reasonable tactical arrangement, is it really honorable? The victors of the war sing the praises of the commander, reward the survivors, and then give the victims far less "honorable" compliments (and they cannot hear them anyway); the losers of the war can only learn their lessons, Remembering history, at leisure, inflict no more than five seconds of mercy on the dead.

I don't see where the "glory" is. In the final analysis, "honor" in the general sense, that is, the praise of the courage to die for the country, is just a rhetoric against the living - a rhetoric to make existing soldiers stop thinking about the meaninglessness of their actions. When a soldier is ready to die on the battlefield when he enlists, even if he is sacrificed as cannon fodder, he pre-orders "glory" in this sense in advance, but his "glory" will be lost when he dies. It will take effect from that moment, and it does not belong to the ta, but to the surviving family members of the ta. The dead can only envision their own glory when they are alive, but can never confirm it for themselves.

I have always believed that the only true glory of the individual should be to survive on the battlefield. On the other hand, the honor that belongs to the commander and the collective should be to avoid the sacrifice of any individual. As long as one soldier experiences an involuntary death, neither side of the war can be honored.

I support the war of self-defense, and I also agree with the feat of driving the US military back to the 38th parallel. But I don't think there is any glory in it.

Today, people tend to appreciate grand narratives, ignore or even depreciate the value of individuals, glorify the victory of wars, and be complacent that their own dignity is manifested. Moreover, in literary and artistic works, people often personify the country and the army, and compare the casualties suffered by soldiers to the healable wounds on individual limbs.

This blunt metaphor downplays the brutality of war, completely ignores the irreparable casualties of soldiers, and focuses on the individual victories and gains of the "nation", which is absurd.

Finally, I hope that future war films can focus on "the devils who provoked wars, and any war is not worth mentioning with cheers", rather than "my country is powerful, we won the battle"!

View more about Paths of Glory reviews