"Tony Takiya" is one of the texts of this semester's contemporary Japanese film course, a film with very critical potential. Since it is adapted from Haruki Murakami's novel of the same name, the film's imitation of the original style also makes it reveal a strong postmodernist spirit. The loneliness presented in the film is gentle and restrained, yet full of tension, interrogating the spiritual melancholy of (post)modernism. For me, the sequelae of watching movies has continued to this day, or even longer.

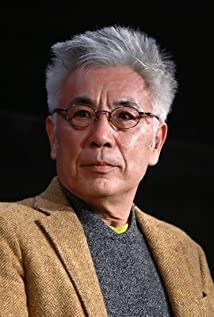

"Tony Takiya" is an early short story by Haruki Murakami, first published in Japan in 1994. Although it may not be one of Murakami's often discussed works, some important themes of Murakami's writing, such as traumatic memory, identity, loneliness, etc., are already shown in Tony Takitani. The story line is very simple and revolves around the lonely life of Tony Takitani. This strange combination of American and Japanese names (Tony Takitani) has put him in an unacceptable environment since he was a child. In 2004, Comrade Ichikawa adapted the story into a film of the same name. With his consistent left-to-right camera movement and choppy narration (often copied from Murakami's original text), he largely preserves the literary style of the original text. In this 75-minute film, the director visually condenses the life experiences of Tony Takiya and his father Shozaburo, but he seems to have made more attempts at portraying female characters. The most obvious is that the women in Murakami's novels are not named, but all appear with the third-person symbol of "she". In a way, Ichikawa's film gives these female characters special identities by naming them, as does the underlying relationship between Tony Takiya's name and his identity.

Female identity under the male gaze

According to British feminist film critic Laura Mulvey, "In a world arranged by sexual imbalances, the pleasure of viewing is divided into active/male and passive/female." (Laura Mulvey 1989, 19) This binary opposition between the sexes is on full display in most narrative films, which typically portray women as a stared figure, while men dominate the viewing behavior. In "Tony Takiya", the active and passive relationship is established in the scene where Tony meets Eiko for the first time.

On behalf of the publisher, Yingzi came to fetch Tony's drawings, and as she left, the camera captured her back and Tony's gaze as she left by the window. The positions of the camera and the characters visually reflect Yingzi's state of being stared at. In an implicit sense, her image is also shaped in Tony's eyes. This passivity persists throughout the film. In this scene, Tony states his impression of Yingzi: "a little bird that is about to spread its wings to a distant world", followed by the voice of the narrator: "She is dressed very naturally, as if carried by a special breeze. shrouded."

The metaphor of flying birds and breeze may suggest Yingzi's complex female identity. Both the bird and the breeze imagery seem to contain a metaphor for freedom - however, what happened to Yingzi was the exact opposite of freedom. First of all, comparing women to birds is a kind of weak, delicate and lovable association to some extent. For example, in Ibsen's famous feminist play "A Doll's House", the husband Helmer rarely refers to his wife by the name "Nora", but instead calls her "a singing skylark" ) or "a squirrel". The husband in this show maintains his dominance by controlling his wife. From a feminist perspective, "Lark" and "Little Squirrel" are not merely nicknames for intimacy between couples, but symbolize an objectification of women. The former alludes to Nora's beauty and her husband's pleasing; the latter has to do with her stealing cookies, which Helmer forbids. Nora's words and deeds are constrained by Helmer everywhere. She is not so much a lark as she is a canary in a cage. The use of the word "doll" in the play's title is a direct reference to the objectification of women. Similar to Nora, Yingzi is also a "little bird" who is controlled by people and becomes the object of male gaze.

Whether it is Murakami's novel or Ichikawa's film, almost all descriptions of Eiko are from Tony's point of view. Yingzi's voice as a woman is somewhat ignored in this male-centric narrative. In the movie, when Tony's father asked him why he liked Yingzi, Tony replied: "She seems to be born to dress up". Here, Yingzi's attributes are reduced to her elegant and refined clothing rather than her character as a person. Meanwhile, Yingko, along with her costume, is given a symbolic meaning—an object destined to be gazed upon by men.

gender roles in the family

After Yingzi and Tony get married, Yingzi's main attribute becomes a "wife", and her clothes tend to be secondary. Tony describes Yingzi as a "gifted housewife". In the film, Ichikawa used a set of shots to shoot scenes of Yingzi doing various household chores, in order to draw the role of a competent wife at this moment, but also to show the harmony of the couple's married life - until a discordant note appeared .

In this scene, Yingzi is washing the car, and Tony is watching from a chair not far away. The narrator reads, "There's one thing that's bothering Tony," before the camera gives Tony a close-up of his face, his smile fading, while he complains: "She buys an amazing amount of clothes." This sequence of shots Alluding to Tony's dominance in the family. First, Tony was looking down at Yingzi from a slightly elevated position. Moreover, Tony in the picture is relatively still, but dominates the interaction between the two, while Yingzi is relatively passive.

Then, the camera moves to Yingzi's feet. What follows is a montage of high heels, flats, and assorted shoes as she walks between boutiques.

Ichikawa uses this symbolism skillfully to express Eiko's madness about shopping. It also hints at the economic boom in Japan during this period, the 1980s. On the one hand, the stability of the post-war family, the security of income, and relatively loose economic policies enabled her to spend a lot. This obsession with shopping reached a fever pitch at one point during their European honeymoon:

In Milan and Paris, she wandered around fashion stores from morning to night. The two did not go anywhere, not even Notre Dame Cathedral and the Louvre Museum. There are only memories of fashion stores in terms of travel. Valentino, Missoni, Saint Laurent, Gibashi, Ferragamo, Armani, Selti, Jean Franco Philae... The wife only knows how to buy one by one with ecstatic eyes Non-stop, and he kept paying after him, really worried that the magnetic strip on his credit card would wear out. (Quoted from the original text by Haruki Murakami)

Yingzi's shopping spree is an illusory pleasure based on spending Tony's money. But on the other hand, her consumption behavior is also restricted by her husband. Tony's request for her to refrain from shopping indirectly led to her death. In its social context, this seems like a metaphor for the collapse of the bubble economy. From a gender perspective, it also hints at the oppression of female desires by patriarchal structures.

While working in a publishing house, she could defer to her own desires and spend almost all of her salary on new clothes. After marriage, however, her sense of self was stripped away along with her consumption autonomy.

In terms of self-awareness, Yingzi differs from Nora in that: Nora's independent consciousness is awakened by her discovery of her husband's hypocrisy; on the contrary, Yingzi's self-independence is gradually dissolved by the role of wife. When she dated Tony before marriage, she once revealed the strong desire in her heart:

I feel like clothes...they fill what's missing in me...I'm self-centred. I like to pamper myself...so, I spend almost my entire salary on clothes. (English sub)

Going back to the previous metaphors about "flying bird" and "breeze", if "bird" represents the objectification of women, then by reading "wind", one may find an effective interpretation of Yingzi's "self-centeredness". Her first appearance in the film is in a panoramic shot where the wind blows her hair as she walks from the other side of the bridge. In fact, throughout the film, the wind is often present with her, even indoors. There is a typical scene after her ecstatic shopping behavior: the breeze blows gently through her hair and the streamers on her clothes, and after a while, she collapses on the bed.

As she says, consumption can fill her void. Here, the breeze expresses a latent female spirit, symbolizing the pursuit and satisfaction of self-desire. On the surface, Yingzi seems to want to be a competent wife, and she accepts Tony's advice to try to curb consumption. However, this scene about the wind reveals her sense of self that is obscured by the role of the wife. In other words, Yingzi subconsciously did not fully agree with her identity as a wife, and even felt pressured to play a qualified wife. It was shopping that brought her back to her inner world and found the possibility to release her desires. At the same time, when Yingzi's desire is suppressed, Feng also shows a kind of resistance in the film.

A glass shatters behind them in the scene where Tony begs her to moderate her consumption. There was no one else in the room but the two of them at this time, so it seemed that only the wind could do this. The breaking of the glass also heralded Yingzi's subsequent mental and physical collapse. An overwhelming emptiness hits her as her husband's pleas repress her desires, killing her in a car accident returning her clothes.

Furthermore, the freedom and agility of the wind is in stark contrast to Tony's meticulousness. After Yingzi died, there was a close-up of more than 10 seconds depicting Tony's wind-ruffled hair. In this story, Yingzi undoubtedly has a crucial influence on Tony. Even after her death, Tony tried to continue her presence by finding a replacement for Yingko. The most visible effect of this is that she changed Tony's understanding of loneliness.

Loneliness and castration anxiety

Haruki Murakami's novels often feature male protagonists, while female characters play different roles in his upbringing or pursuits. This pattern also applies to "Tony Takiya". Before meeting Yingzi, Tony thought loneliness was the most natural thing. The early death of his mother and the absence of his father during childhood forced him to get used to living alone at an early age. This childhood trauma of parental absence offers the possibility of an Oedipal reading of it. His father's departure coincides with his subconscious desire to kill his father, while his mother's death symbolizes that the object of his subconscious desire is also deprived. As a result, his desires turned to painting, machinery and other delicate things. And he was extremely indifferent to everything that happened around him.

However, the encounter with Yingzi plunged him into an unprecedented anxiety and panic:

The loneliness suddenly became a burden that overwhelmed him and made him miserable. Loneliness, he thought, was like a prison, but he hadn't noticed it before. He continued to stare desperately at the solid, cold wall that surrounded him. If she said she didn't want to get married, he would probably die like that. (Quoted from the original text by Haruki Murakami)

Tony's negativity is a Freudian symptom of castration anxiety when a boy sees a woman without a penis. Lacan then uses this sexual difference as a starting point to illustrate the process by which men identify their subjectivity. Freud's psychoanalysis is rooted in phallocentrism. In his seminal essay "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema," Mulvey argues that phallocentrism is a paradoxical system because it relies on castrated women to give men order and meaning: "It is her lack that makes phallus a symbolic being, and what phallus refers to is her desire to make up for the lack." (1989, 14) In Tony's cognition, it is It was Yingzi's appearance that made him feel a kind of loneliness that existed in essence but "wasn't aware of it before". Yingzi's presence makes loneliness tangible. In a way, his loneliness is a symbolic phallus. In Murakami's text, male loneliness is manifest, while female loneliness is hidden beneath the surface. In Ichikawa's films, Yingzi's loneliness is also easily overlooked by Tony-centric narratives. Ichikawa describes Eiko's emotions as missing, also suggesting the lack of a symbolic phallus.

Mulvey's interpretation of the paradox of phallocentrism shows the dual role of women in men. On the one hand, women are the objects of male desire; on the other hand, men feel anxious when confronted with them. In this story, Yingzi is the key to Tony's affirmation of his self-subjectivity, and she brings Tony out of his previous mechanical world to perceive the warmth, loneliness, and other chaotic emotions of an ordinary person. For a few months after their marriage, Tony was trapped in the fear of losing his son and falling back into loneliness, a sign of castration anxiety. Mulvey also points out two ways to relieve anxiety in the article: voyeurism that recreates the original trauma, and fetishism that completely negates castration (1989, 14). Tony apparently takes the second route subconsciously, which is to try to erase the trauma and find a replacement for the trauma (Kyuko). In the film, director Ichikawa subtly conveys the relationship between substitution and substitution through the technique of playing two roles (Miyazawa Rie plays both Yingko and Hisako). And in the scene where Tony meets Yingzi's ex, he resists traumatic memories with a negative expression of forgetfulness.

All in all, "Tony Takiya" is an allegorical film about postwar Japanese society. Ichikawa largely retains the melancholy atmosphere and restrained brushstrokes of Murakami's original work, but it explores female identities more deeply, albeit still as a male-centric narrative. In traditional Japanese families, women tend to be objectified and dehumanized under the patriarchal structure, so Eiko is also reduced to the object of gaze. However, the identity of Yingzi in the film is complicated. The consumption mania during the economic boom is a metaphor for the underlying female desire and self-consciousness; however, under the influence of gender power relations, this female spirit is constrained by the role of the wife and struggles. . At the same time that men form a binding relationship with women, Yingzi's female identity also enables Tony to construct his own subjectivity, which is specifically represented as loneliness, which to some extent alludes to the castration anxiety in psychoanalysis. Yet in this lonely scene, women are aphasia and absent.

View more about Tony Takitani reviews