film is straightforward and concise, and most of its length is a transcript of the dialogue between the Gestapo interrogator Mohr and Sophie. The scene is Mohr's office. It sounds boring, but in fact it is not at all. The interrogation and dismantling, and the tit-for-tat debate, make people concentrate and sigh.

Sophie and her brother, as well as a few friends who print flyers in the university, have no party background, nor are they Jewish, they are ordinary intellectuals. Out of conscience, they criticized Nazi tyranny and advocated nonviolence and noncooperation. As Sophie said, the truth is that, we just say what we all know but don't say. In the movie, most people are either cooperative or silent towards the Nazis, such as the administrators who actively inform the university, and the professors and classmates who retreat. The Gestapo wears suits and bow ties, asks for confessions, and executes murder missions, like screws in a machine, without emotion, just moving on track. Mohr in the system, after talking with Sophie, may be at war with one another and obviously exhausted, but he still follows the rules.

When the Nazis were rampant in Germany at the time, it could not have been done by Hitler alone or by a few members of the National Socialist Party. Silence, tolerance and acquiescence to tyranny are actually co-obedience. No one is qualified to make moral judgments on everyone, but when a few individuals, even under the violence in the dark and facing the guillotine, choose to uphold their conscience and tell the truth, they are admirable, they let I feel the good side of human nature. Sophie said, strong will, gentle heart.

This small-budget film seems to be earth-shattering, but it gave me a shock in my heart, and it provides us with an angle to examine the problem. Whether it is to reflect on oneself or to examine the surroundings, there is a practical cautionary significance.

Sophie and Mohr perform well, and Mohr is even worse.

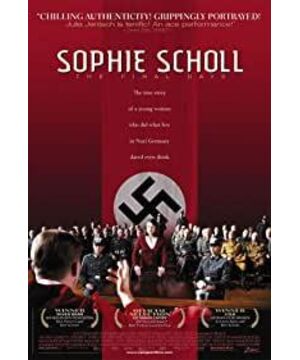

View more about Sophie Scholl: The Final Days reviews