trauma of sound

Putting Chaplin under the symbol of "death and sublimation" may seem odd, even absurd: Chaplin's cinematic world, a world bursting with unsublime vitality, even vulgarity, is not a sense of death and vulgarity? Is sublimation the opposite of a romantic obsession? Maybe so, but at one particular point, things get complicated again: the point of intrusion of voice. It is the voice that makes the burlesque of silence, so unrestrained in destruction and destruction, that the pre-Oedipal, colloquial-anal paradise, ignorant of death and sin, loses its innocence: "In the colorfulness of burlesque A world in which there is neither death nor crime, where everyone sends and receives blows as they please, cream cakes fly, and buildings fall amidst widespread laughter. This world of pure gestures, It is also the world of cartoons (an alternative to the farce of the past), where the protagonists are generally immortal .… This pre-Oedipal world of perpetual continuity: it acts as a strange body that stains the innocence of the image; a ghostly apparition that cannot be fixed on a finite visual object. This changes the whole economics of desire, the naive and vulgar vitality of silent films is lost, and we enter the realm of double meanings, hidden meanings, repressed desires - the presence of sound changes the visual surface into something deceptive something, a seduction: "The film is full of joy, innocence, and filth. It will become stubborn, fetish, and cold-blooded."[2] In other words: the film was Chaplin's, it will be Hitchco's grams. It is no accident, therefore, that the arrival of sound, the sound film, introduced a duality into Chaplin's world: the uncanny schism of the tramp figure. Recall three of Chaplin's great sound films: The Great Dictator and Monsieur Verdoux) and Limelight, they are both known for the same melancholy, wrenching humor. They all raise the same structural problems: the problem of an indistinct line of demarcation, the problem of a character whose presence or absence we have difficulty identifying at the level of certain attributes, whose presence or absence Fundamentally alters the symbolic status of the object: the difference between a Jewish barber and a dictator is as trivial as the difference between their respective beards. But their endings were infinitely different, as vast as the difference between the victim and the executioner. Likewise, in Monsieur Verdu, the difference between two faces or manners of the same man, the difference between the killer of an old woman and the good husband who takes care of his paralyzed wife, is so subtle that everything about his wife All intuitions depend on the hunch that he has somehow "changed"... The intriguing question of "The Spring and Autumn of the Stage" is: what is the "emptiness", the sign of the era, the ordinary little difference? What, thanks to it, the figure of funny clowns turned into a tedious spectacle? [3] The character of this difference, which cannot be fixed in a definite quality, is what Lacan calls le trait unaire, the ineffable character: the point of symbolic identification to which the reality of the subject attaches. As long as the subject is fascinated by such a feature, we are faced with a charismatic, heady image; once this fascination is broken, nothing but a dull remnant remains. What we should not overlook, however, is how such a split is conditioned by the arrival of the voice, the fact that the figure of the tramp is compelled to speak: in The Great Dictator, Siegel chattering, and the Jewish barber is closer to the silent tramp; in "The Spring and Autumn of the Stage", the clown on the stage does not say a word, but behind the stage, the resigned old man is talking... So, Chaplin to the voice The well-known disgust of , should not be dismissed as a simple, nostalgic commitment to silent paradise; it reveals something deeper than usual knowledge (at least a hunch) that sound has destructive power , is an external body, a parasite that triggers a fundamental division: the arrival of the word disrupts the balance of the human animal and reduces him to an absurd, impotent figure, gesturing desperately for a lost balance. This destructive power of sound is featured in City Lights Light), in that ambivalent silent film with a soundtrack, it couldn't be more clear: a soundtrack without words, just music and some typical noise about the object. It is here that death and sublimation, with all their energies, erupt.

The intervention of the homeless

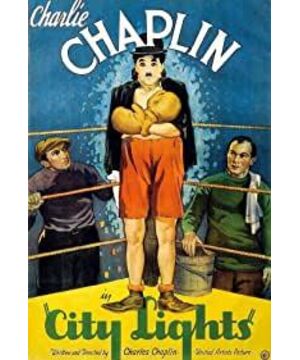

In the entire history of cinema, "City Lights" is perhaps the purest example of a movie that stakes its entire stake on the final act, arguably - the whole movie is ultimately just for the final, ending moment Be prepared, and when the moment comes, when (in the last phrase of Lacan's "Seminar on the 'Stolen Letter'") "the letter reaches its destination",[4] the film can immediately it's over. So the film is structured in a strictly "teleological" way, with all its elements pointing to the final moment, the long-awaited climax; which is why we can also use it to question the usual The procedure of teleological deconstruction: it may herald a movement towards the end that escapes the teleological economy depicted (and we don't even have to say: reconstruction) in a deconstructive reading. [5] "City Lights" tells the story of a homeless man's love for a flower girl. On the bustling street, the blind girl mistook him for a rich man. After a series of adventures with the same eccentric millionaire (who treats tramps with great friendliness after being drunk, but doesn't recognize him when he wakes up [here's where Brecht got his His "Puntilla and his Servant" Matti) inspiration? ]), the homeless was paid for the surgery needed to treat the blind girl; but he was also caught as a thief, arrested and put in jail. After his sentence is over, he wanders the city desolately alone; suddenly, he passes a flower shop and sees the girl. The girl's operation was very successful, and her business is booming now, but she is still waiting for the Prince Charming of her dreams. Whenever a handsome young customer entered the store, she was full of hope; but after hearing the voice, she was repeatedly lost. The tramp recognizes her quickly, though she doesn't recognize him because all she knows about him is his voice and the touch of his hand; she looks through the window (which separates the two like a screen) What you get is just the absurd image of a homeless person, the scum of a society. Seeing the rose (the girl's memento) fall from the hand of the tramp, the girl feels pity for him, his passionate and desperate gaze arouses the girl's sympathy; thus, the girl does not know who or what awaits her, she still In a cheerful, even sarcastic mood (she said to her mother in the shop: "I conquered one!"), took to the pavement, gave the tramp a new bouquet of roses, and put a coin Press into his hand. It was at this moment, when their hands touched, that she finally recognized him by touch. She woke up immediately and asked, "Is that you?" The tramp nodded, pointed to his eyes, and asked her: "Can you see now?" The girl asked: "Yes, I can see now"; The film goes on to give the tramp a photographic close-up, his eyes full of horror and hope, smiling shyly, not knowing how the girl will respond, content and at the same time uneasy about being completely exposed to her - that's the film ending. At its most basic level, the poetic effect of this scene is based on the double meaning of the final dialogue: "I can see now" refers both to the girl's restored vision and to her being able to see who her Prince Charming really is, Namely the fact of a poor bum. [6] This second meaning puts us at the heart of the Lacanian problem: it is concerned with the residual, residual, object-excretory relationship between symbolic identification and escaping identification. We would say that the film shows what Lacan calls "separation" in Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, the separation of I and a, the ideal of the ego (Ego Ideal), the symbolic identity of the subject, and the separation of the object: the object is detached and isolated from the symbolic order. [7] As Michel Chion points out in his excellent reading of City Lights,[8] the fundamental characteristic of the tramp figure is his interposition: he always Between a gaze and the "intrinsic" object of that gaze, to fix upon itself a gaze destined to belong to something else (the ideal focus or object) - he is a stain that disturbs the gaze and its" The "direct" communication between the "inherent" objects leads the direct gaze astray, turning it into a strabismus. Chaplin's comedic strategy is contained in a variation on this fundamental theme: the tramp accidentally takes a position not his own and destined not for him - he is mistaken for a rich man or a different person guest; in escaping pursuit, he finds himself on stage, suddenly at the center of countless stares... In Chaplin's films we even find a kind of The crazy theory that comedy stems from the blindness of the audience is that comedy stems from such a rift caused by the wrong gaze: in The Circus, for example, the homeless man escaping the police finds himself in the circus on a rope at the top of the tent; he begins to gesture frantically, trying to keep his balance, while the audience laughs and applauds, mistaking his desperate struggle for life for the virtuosity of a comedian - and that's exactly what we're getting at Cruel blindness, to seek comedy in ignorance of the tragic reality of a situation. [9] In the opening scene of "City Lights", the homeless person plays the role of such a stain on the picture: in front of a large audience, the mayor unveils a new monument; when he lifts the white veil, he is surprised spectators found the Tramp sleeping peacefully on the lap of the giant sculpture; the Tramp, awakened by the noise and realizing that he was the unexpected focus of thousands of eyes, tried to climb down the sculpture as quickly as possible, while his clumsy The effort made the audience laugh again... In this way, the tramp becomes the object of a gaze aimed at something else or a person: he is mistaken for something else, and accepted as such, otherwise—as soon as the audience realizes the mistake—he It's a disturbing blemish that people want to get rid of as quickly as possible. Thus, his basic longing (which also served as a clue to the final scene of "City Lights") is ultimately to be accepted as "himself", not as a substitute for another person - and we'll see When the tramp exposes himself to the gaze of others, presents himself without the support of any ideal identification, he is reduced to his remaining naked existence as an object, and this moment is far from More ambiguous and dangerous than it seems. The misidentification-inducing accident in City Lights comes shortly after the opening scene. In order to cross the road while dodging the police, the homeless man begins to cross the vehicles that are standing still in the traffic jam; when he gets out of the last car and closes the rear door, the girl spontaneously puts this sound - the door closing - connected with him; this and the hobo's generous payment for roses - his last coin - created in the girl's mind the image of a charitable millionaire with a luxury bridge car. Here is automatically presented a kind of Northwest), where Roger is mistaken for the mysterious American agent Caplin by a chance coincidence (when the clerk walks into the bar shouting "Mr. Caplin's Phone!", he happens to make a gesture to the clerk): here, too, the subject finds himself unexpectedly occupying a place in the symbolic network. Here, however, the parallel goes even further: it is well known that the basic paradox of the plot in North by Northwest is that Roger is not simply mistaken for another person; he is mistaken for someone who does not exist at all. Man, a fictional operative made up by the CIA to distract from the real operative; in other words, Roger finds himself occupying and filling a void in the structure. And that's why Chaplin kept delaying filming the misidentification scene: filming dragged on for months and months. As long as Chaplin insisted that the rich man the tramp was mistaken for was a "real person", another subject in the film's narrative reality, then the result would not satisfy Chaplin; and the solution was precisely Chaplin suddenly realized that rich people don't have to exist at all, he just needs to be the fantasy formula of poor girls, that in reality, one person (the tramp) is enough. This is also one of the fundamental insights of psychoanalysis. In the network of intersubjective relations, each of us is identified as a fantasy position in the semiotic structure of others, and is fixed there. What psychoanalysis insists here is precisely the opposite of the usual platitudes (according to these platitudes, fantasies are nothing more than distortions, mixtures and connections of the "real" images of the flesh and blood we encounter in our experience). Only when we can identify these "flesh and blood" as a place in our symbolic fantasy space, or, to put it more tragically, only when they can fill a pre-established place in our dreams. Get in touch with them - we fall in love with a woman as long as her characteristics match our fantasy image of a woman, and a "real father" is a man forced to take on the name of the The tragic individual with the heavy responsibility of the Father, who was never able to fully assume the mandate of his symbols, etc. [10] Thus the role of the tramp is that of a mediator, a middleman, a contractor: an intermediary, a messenger of love, between himself (i.e. his own ideal image: the fantasy image of a wealthy Prince Charming in the girl's imagination) and between girls. Or, as long as the rich man ironically embodies the eccentric millionaire, the tramp is somewhere between him (the rich man) and the girl - whose role is ultimately to transfer money from the rich man to the girl (which is why, Structurally speaking, millionaires and girls necessarily never meet). As Joan shows, this mediating role of the tramp can be perceived through the metaphorical connection of two consecutive scenes that have no common ground at the narrative level. The first scene takes place in a restaurant where a homeless man is being entertained by a rich man: he eats pasta in his own way, and when a roll of ribbon falls on his plate, he mistook it for noodles, went on to devour it, and ate it Hold up, tiptoe (the ribbon hanging from the ceiling is like a gift from heaven) until the rich man cuts it; a basic Oedipus plot is thus revealed - the ribbon is a metaphorical , the umbilical cord that connects to the maternal body, and the rich man acts like a surrogate father, severing his connection to his mother. In the next scene, we see the homeless man at the girl who asks the homeless man to hold the yarn for her so that it can be rolled up; the blind girl accidentally grabs the end of his woolen underwear coming out of his jacket , the garment is disassembled by pulling the thread and rolling it up. From this, the connection between the two scenes is obvious: what the homeless gets from the millionaire, the food that is swallowed, the endless ribbon, is now poured out of his mouth and given to the girl. And—and here is our proposition—for that reason, in City Lights, the letter reaches its destination twice, or, to put it another way, the messenger rings the doorbell twice: The first time is when the tramp succeeds in handing over the rich man's money to the girl, i.e. he successfully fulfills his role as an intermediary; the second is when the girl recognizes in the absurd image of the tramp the benefactor who made the operation possible . When we can no longer legitimize ourselves as mere mediators and contractors of the letters of the Big Other, when we no longer fill the ideal place of the self in the fantasy space of the Other, when the heavy presence of ideal identity and symbolic representation When there is a separation between us, when we no longer serve as ideal placeholders for the gaze of the other, the letter finally reaches its destination—in short, when the other confronts our grief. The letter finally reaches its destination when it loses what is left of the symbolic support. When we are no longer "fillers" in the vacancies in other people's fantasy structures, i.e. when others finally "open their eyes" and realize that real letters are not the messages we are supposed to deliver, but our very existence, the symbol of resistance in us As the object of transformation, the letter reaches its destination. It is this stripping that takes place in the final scene of "City Lights."

peel off

Until the end of the film, the Tramp is limited to an intermediary role, cycling between the two figures (the rich man and the poor girl, who make up the ideal couple) and making possible the communication between them, as well as their The barrier to direct communication between them is the stain that prevents them from directly contacting, an intruder who is never in his place. However, with the final scene, the game is over: the tramp finally exposes himself to his presence, he is here, he does not represent anything, does not fill anyone's place, we must accept him, or reject him . The genius of Chaplin is his decision to end the film in such abrupt and unexpected way when the tramp is exposed: the film does not answer the question "Will girls accept him?" - girls will accept tramps, And the idea of the two living happily together afterwards has no basis in the movie. That said, in order to create the usual happy ending, we need an extra shot that corresponds to the hopeful and trembling gaze of the tramp at the girl: for example, the girl in turn gives a hint of acceptance, followed, perhaps, by the two embracing lens. We don't find anything like that in the movie: in a moment of absolute uncertainty and openness, the movie ends, and the girls—and us the audience—are directly confronted with a "love your neighbor" question. Is this absurd, clumsy creature, whose heavy presence hits us suddenly with an almost unbearable approach, really worthy of her love? Can she accept and take on this social scum to which she has found answers to her ardent desires? As William Rothman points out,[11] the same question has to be asked in the opposite direction: not only "is there a place for this ragged creature in her dreams?", but also "Is there still a place for her in his dreams, she is now a normal, healthy girl, running a successful business?" - In other words, isn't it precisely because of her that the tramp develops such sympathy for the girl Blind, poor, utterly hopeless, in need of his protection and love? Now, when she has every reason to support him, will he still be happy to accept her? When Lacan wrote in The Ethics of Psychoanalysis (L'éthique de la In psychanalyse), he emphasized Freud's limitation on the Christian "love of one's neighbor",[12] he meant precisely this awkward dilemma: loving the idealized image of a poor, helpless neighbor and It is not difficult, for example, to be African or Indian; in other words, it is not difficult to love one's neighbor, as long as he is far enough away from us, as long as there is a proper distance between us. The problem is when he gets too close to us, when we begin to feel his suffocating approach—when this neighbor exposes himself too much to us, love turns into hatred in an instant. [13] "City Lights" ends at this moment of absolute uncertainty, and we are all faced with the imminence of the Other as an object, and have to answer the question: "Is he worthy of our love? ?" Or, to use Lacan's formula: "Is there something in him beyond itself, the small object a [objet petit a], a hidden treasure?" Here we can see that in this How far we are from the usual teleological notion of the moment when "the letter reaches its destination": this moment, far from fulfilling a preordained purpose, marks the intrusion of a radical opening in which All ideal supports are suspended. This moment is the moment of death and sublimation: when the subject's presence is exposed outside the symbolic support, he "dies" as a member of the symbolic community, his existence is no longer determined by a certain position in the symbolic network , it materializes the pure nothingness of the void, the fissure in the Other (symbolic order), which Lacan designates in German as das Ding, the thing (the Thing), a pure entity that resists symbolic pleasure. Lacan's definition of the sublime object is precisely "an object elevated to the dignity of things". [14] When the letter reaches its destination, the stain that tramples on the picture is not abolished or erased: on the contrary, what we are forced to grasp is the fact that the real "information", the real letter that awaits us , it is the stain itself. We should interpret Lacan's "Seminar on 'Stolen Letters'" in this respect: isn't the letter itself such a stain - not a signifier, but an object that resists signification, a surplus, A residue of matter, circulating between subjects, tainting its ephemeral holder? Now, to conclude, we can go back to the opening scene of City Lights, in which the tramp is a disturbing stain, a stain on the white marble surface of the sculpture: from Lacan's point of view, the subject is strictly The ground corresponds to this stain on the screen. The only evidence we have of the subjectification of the image we are looking at is not the meaningful symbols in it, but the presence of some meaningless stain that disturbs its harmony. Let's recall the counterpart to the original scene of "City Lights", the final scene of "The Spring and Autumn of the Stage," in which Chaplin's body is also covered with a white cloth. This scene is unique in that it marks the point at which Chaplin and Hitchcock, two creators whose art worlds seem utterly incompatible at the level of form and content, finally meet. That said, Chaplin finally seems to have discovered Hitchcock's push-pull shot in "The Spring and Autumn": the first shot of the film is a long-distance push-pull shot, from a vista of an idyllic London street, Progress is made to a closed apartment door leaking deadly gas (it suggests a suicide attempt by the young girl living in the apartment), and the film's final scene contains a magnificent backwards push-pull shot from A close-up of the late Clown Carbelle, progressing to a vista of the entire stage, where the same young girl, now a successful ballerina, his beloved, is performing. Just before this scene, the dying Carbelle expresses to the attending doctor his desire to see his beloved dance; the doctor gently pats him on the shoulder and comforts him, saying: "You will see her! "Afterwards, Carbelle dies, his body is covered with a white sheet, and the camera starts to move back to show the dancing girls on the stage, while Carbelle is reduced to a tiny, almost-looking figure in the background. Invisible white stain. Crucially here, it is the ballerina who comes into the picture How: From behind the camera, like in Hitchcock's Birds, the birds in the famous "God's View" of Bodega Bay—another white smear that embodies the The mysterious intermediary space in which the viewer is separated from the narrative reality on the screen... Here we meet the function of the gaze as the purest object-stain: the fulfillment of the doctor's prophecy, precisely when the clown dies In other words, as long as Carbelle couldn't see her, he watched her. For that reason, the logic of this backwards push-pull shot is completely Hitchcockian: through it, a patch of reality becomes an amorphous smudge (a white smudge on the background) around which the entire field of vision revolves The smudge rotates, and the smudge "smears" the entire field (like the backward push-pull shot in Frenzy)—the ballerina dances for it, for the smudge. [15]

Translated from Zizek, Enjoy Your Symptom!, New York & London: Routledge, 2001, pp. 1-9.

Notes: [1] Pascal Bonitzer, Le Champ aveugle, (Pairs: Cahiers du Cinéma/Gallimard, 1982), pp. 49-50. [2] Ibid., p. 49. [3] Gilles Deleuze, L'Image-mouvement ( Pairs: Editions de Minuit, 1983), pp. 234, 236. [4] Cf. Jacques Lacan, “Seminar on 'The Purloined Letter',” in John P. Muller and William J. Richardson, eds., The Purloined Poe (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988), p. 53. [5] Among recent films focusing on the final scene, Peter Weir's Dead Poets Society should be mentioned. Poet's Society): Wasn't the whole story a build-up to bring about the final tragic forte - the students defying the authority of the school by standing on the bench and expressing their determination to stand in solidarity with the fired teachers? [6] The fact that the final dialogue takes place in complete silence—we read the dialogue in the interlude of the silent film—gives the film an extra intensity: as if the silence itself begins to speak. At this point, the intrusion of sound destroys the entire effect, or rather: it destroys its sublime dimension. This scene justifies Chaplin's "perverse" decision to produce a silent film in the age of sound, since the entire effect of the sequence stems from us - the audience - knowing that the film has spoken and thus taking the experience of this silence as a part of the voice. The fact of absence. [7] Jacques Lacan, The Four Foundamental Concepts of Psycho-analysis (London: Tavistock Publication, 1977), chapters 17 and 20. [8] Michel Chion, Les Lumières de la ville (Pairs: Nathan, 1989). [9] It should be noted that City Lights itself sprang from a similar idea. It was originally the story of a father who lost his sight in an accident; to avoid the mental trauma of his young daughter when he learned of his blindness, he pretended to be blind due to clumsiness (overturning a chair, falling, etc.) is a comedic parody of a clown to please the daughter; and the girl accepts this explanation without doubting the real condition, with a hearty laugh at her father's misfortune. [10] The split between the ideal image of the rich and the tramp as the object of the ideal image also allows us to locate the paradox of female self-destructive curiosity, from Wagner's work to contemporary popular culture. That said, the plot of Wagner's Lohengrin opens up Elsa's curiosity: an unsung hero saves her and marries her, but asks her not to ask who he is, or that he What's the name of her ("Nie sollst du mich befragen" [Nie sollst du mich befragen]) - once she does, he will be forced to leave her... Elsa couldn't stand it and asked him fatal questions; thus, in an even more famous track ("In fernem Land," Act III), Lohengrin told her, He was the Holy Grail Knight, the son of Parsifal from Bangsawat City, and then Lohengrin went away on a swan, and the unfortunate Elsa died of grief. Why not recall Superman or Batman here and we will find the same logic? In two instances, the heroine has a premonition that her partner (the confused reporter in "Superman", the eccentric millionaire in "Batman") is really a mysterious mass hero, but the partner delays the reveal for as long as possible moment. What we have here is a forced choice that confirms the castration dimension: the man is divided, he is divided into the cowardly, the everyday person whose sexual relations are possible, and the bearer of the symbolic mandate, the popular hero (Knight of the Holy Grail). , Superman, Batman); we are thus forced to choose: as long as we force our sexual partner to reveal his symbolic identity, we are doomed to lose him. So, when Lacan says that the "secret of psychoanalysis" consists in the fact that "sexuality does not exist, and therefore has sex," action is precisely to be regarded by the subject as a performative assumption of its symbolic mandate, as In "Hamlet," the moment when Hamlet is finally - albeit too late - able to act is marked by his expression "I, Hamlet the Dane": this is what is impossible in the sexual order, That is, as soon as a man speaks of his appointment, as in "I...Lohengrin, Batman, Superman," he excludes himself from the realm of sexuality. [11] William Rothman, “The ending of 'City Light'” in The “I” of the Camera (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), p. 59. [12] Cf., Jacques Lacan, Le Séminaire, livre VII: L'éthique de la psychanalyse (Pairs: Editions du Seuil, 1986). [13] Or to cite the example of Westerns: it is not difficult to love Indians when they are portrayed as helpless and cruel victims, as in The Broken Arrow or The Broken Arrow. Soldier Blue; but when it comes to John Ford's Fort Apache, things get more ambiguous because the Indians were murderous there and they were militarily Even better, it ravaged the American cavalry like a gust of wind. [14] Jacques Lacan, Le Séminaire, livre VII, p. 133. [15] It would be interesting to read "The Spring and Autumn of the Stage" as a supplement to "City Lights": at the end of "City Lights" the tramp "begins" life” (he is recognized in his real existence), and at the end of Stage Spring and Autumn, he dies; City Lights begins with the removal of the tramp (the mayor unveils the statue), and Stage "Spring and Autumn" ends with the covering of his body; in "City Lights", the tramp finally becomes the complete object of other people's gaze, while in "Stage Spring and Autumn", he himself becomes a pure gaze; In "City Lights", the girl, the mutilation of her beloved, refers to the eyes (blindness), while in "The Spring and Autumn of the Stage" it is the feet (paralysis: the original title of the film is "Stage Foot Light"); and so on. The two films have to be understood in the Levi-Stress way, as two versions of the same myth. [15] It would be interesting to read Stage Spring and Autumn as a supplement to City Lights: at the end of City Lights, the tramp "begins to live" (he is recognized in his real existence), while At the end of "Stage Spring and Autumn", he dies; "City Lights" begins with the unmasking of the homeless (the mayor unveils the statue), and "Stage Spring and Autumn" ends with the cover of his body; in "City Lights" In "The Spring and Autumn", he himself becomes a pure stare; in "City Lights", the girl, the mutilation of her beloved , refers to the eyes (blindness), and the feet in "The Spring and Autumn of the Stage" (paralysis: the original title of the film is "Stage Foot Light"); and so on. The two films have to be understood in the Levi-Stress way, as two versions of the same myth. [15] It would be interesting to read Stage Spring and Autumn as a supplement to City Lights: at the end of City Lights, the tramp "begins to live" (he is recognized in his real existence), while At the end of "Stage Spring and Autumn", he dies; "City Lights" begins with the unmasking of the homeless (the mayor unveils the statue), and "Stage Spring and Autumn" ends with the cover of his body; in "City Lights" In "The Spring and Autumn", he himself becomes a pure stare; in "City Lights", the girl, the mutilation of her beloved , refers to the eyes (blindness), and the feet in "The Spring and Autumn of the Stage" (paralysis: the original title of the film is "Stage Foot Light"); and so on. The two films have to be understood in the Levi-Stress way, as two versions of the same myth.

View more about City Lights reviews