By Jasper Sharp (Sight & Sound)

Translator: csh

The translation was first published in "Iris"

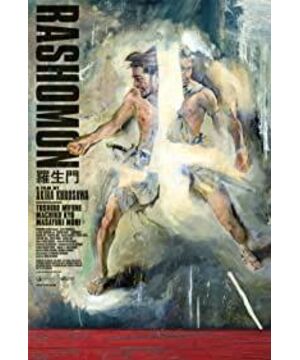

On the 70th anniversary of Rashomon, you might want to take a look back at the milestones in the film's history. Your reasons can be many. It was because of this film that overseas audiences first knew Kurosawa's name. They also got to know stars such as Toshiro Mifune, Kyo Machiko and Shimura Joe from the golden age of Japanese cinema. In 1951, it won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, and it was also a landmark in film history, meaning that the world audience began to take an interest in Japanese films. Additionally, it became the first Japanese film to be released by a major North American studio.

This is an exciting new type of cinema that is emerging from the East. But when Japanese movies first became popular, people were mostly in love with specific period dramas rather than contemporary stories. The image of Japan is not only presented in "Rashomon", but also in a series of art films in the film festival system since then, including Mizoguchi's "Uzumaki Monogatari" and "Sansho Doctor", as well as Kinikasa's Sadanosuke's "Gate of Hell". It is worth mentioning that these films show neither the heyday of Bushido in Japan nor the more recent, feudal Tokugawa period (1603-1868). In the 1950s, these two periods provided the context for most domestically oriented audiences. The films mentioned above show medieval, Heian period (794-1185) Japan. In those days, this near-mythical land was far removed not only from Japanese audiences in terms of life experience, but also culturally from overseas audiences, and as such, it provided fertile ground for allegory, mystery and abstraction. Create soil.

The contribution of Rashomon to the history of film lies mainly in its revolutionary narrative method. It uses flashbacks to introduce narrative uncertainty. In the film, four key witnesses provide conflicting accounts of a major dramatic event. Its screenplay, written by Shinobu Hashimoto, is based on two short stories by the modernist writer Akutagawa Ryunosuke (1892-1927). Its core events are this: a noble woman is violated, her husband as a samurai is murdered in an isolated bamboo forest, and then people try to find out the elusive truth behind the crime - this source In the 1922 story "In the Bamboo Forest". The shorter emotional work Rashomon from 1915 became the title of Akira Kurosawa's work, which describes the natural environment around Rashomon, the southern gate of the ancient capital of Kyoto. After this door, it will lead to the dark, sin-ridden wilderness.

It was this venue that provided the stage for this film. We tried to reconstruct what really happened from eyewitness accounts of the crime: a lumberjack who happened to be in the area, a notorious bandit (who was the main suspect), the wife of a samurai who was raped, and even the The victim of the killing himself, summoned by a psychic, floats out of the grave to give evidence, which adds a supernatural element to the narrative and disrupts the thread of the narrative of individuality.

Even Rashomon itself is depicted as a separate "character," battered by rain and cut off from the world in darkness. As Japanese literature scholar Paul Andler points out, Rashomon is like "another fabler who seeks out in the shadows and emptiness of nothingness after the war".

Clearly, Kurosawa wanted to make the parable clearer. Today, the gate, built in 789, is almost in ruins. Even at the end of the Heian period, it was in such a dilapidated state that it became a haven for thieves, murderers and other outlaws.

In 1919, Akutagawa Ryunosuke saw the building as a symbol, and in his writings, the door represented the unease that swept Japanese society. But at the end of Kurosawa's film, we see an abandoned baby under the destroyed arch - which means that it plays a more important role when the physical existence is about to die. For the tragic historical role: those who are not welcome will be thrown into this garbage dump. According to Andler, in Kurosawa's original conception, it would be surrounded by a series of ramshackle stalls. It's akin to the streets of Tokyo during the occupation, lined with black market stalls. In the end, though, Kurosawa spent a lot of money to rebuild the monumental building in the story. He also hired fire trucks to soak them in the endless drizzle. In this way, he blocks this clear visual connection between the past and the present.

Although Kurosawa had made eleven films at the time, he was far from a local legend or the international guru he would become. Daiei, which financed Rashomon, also had little faith in the project. The studio had just produced a Kurosawa film, The Duel in the Quiet Night (1949). Akira Kurosawa later noted in his memoirs that his next work, Shochiku's The Idiot (1951), an adaptation of Dostoevsky's original, suffered a commercial and critical disaster. , as a result, Daiei withdrew its proposal to make another Kurosawa work.

When Rashomon was released on August 26, 1950, it was not a particularly commercial success. Contrary to popular belief, though, it did well in the critics. The authors of the "Movie Xunbao" named it the fifth best work of the year in the annual top ten. Its subsequent status in the international film industry can be attributed to Giuliana Stramioli, the representative of Italia Films. She saw Rashomon on a trip to Japan and recommended it for the Venice Film Festival the following year. Daiei did not inform Kurosawa of the good news, not even when it won the prestigious Golden Lion. That honor later rescued the director from a post-Idiot slump.

Without a doubt, "Rashomon" has become the most watched Japanese film for over a decade. Its acclaim at the Venice Film Festival led to RKO's decision to release it in North America in December 1951. At that time, the market for what today is called "foreign art films" had not yet been established. As Greg Smith points out in "The Critical Acceptance of Rashomon in the West", major studios have tried to release foreign films with subtitles before, dating back to 1948, when RKO released Silence is Golden (1947) by Rene Claire.

In the UK, Rashomon was released in March 1952. Film Monthly's critic noted that it was "the first film from Japan that the country has seen in many years". A few months later, in August 1952, its distributor, London Films, released a second Kurosawa film, The Man on the Tail (1945) of his early comedy period.

Akira Kurosawa's breakthrough in the international market greatly affected his reputation in Japan. He is considered a Japanese director who caters to foreign audiences. As he wrote in his autobiography, as he won the Golden Lion and the subsequent Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, Japanese critics insisted, "Westerners still retain a curious and curious taste for the exoticism of the East. , it made me feel bad, both then and now.”

The evaluation of Rashomon by some foreign critics does confirm the possibility of this situation. Simon Harcourt-Smith's review of "Sight and Sound" begins with a warning to readers: "This film represents a tradition and a point of view that may be furthest from our world, and it confronts us directly. traditions and perspectives.” The author makes a perverse but suggestive comment, saying that Rashomon “is strangely reminiscent of the moods of the German silent films of thirty years ago, which were also Something created after defeat."

During the seventy years following the discovery of Japanese art by the painter James Whistler, a considerable number of reviews detail the qualities of Japonism. For this reason, the author declares, "it took a certain amount of time and experience for the West to distinguish between the pure novelty and the truly remarkable". Harcourt-Smith often refers to kabuki, and he also points out that "repetition is indeed the distinguishing feature of the art of kabuki," a misleading argument that he is clearly suggesting in Rashomon. The storytelling technique of revisiting the plot from a different angle.

Indeed, while Harcourt-Smith sees Rashomon as "one of the most exciting and extraordinary films the world has seen since the end of World War II," there is also the comment: "We found ourselves witnessing A world in which social conventions and psychological reactions are alien to us, yet infinitely appealing to us.” This assessment is sufficient to point out that most English-language critics, when they write about this work, are actually faced with a disturbing unpleasant fact. The only version it screened at the festival was in Japanese with Italian subtitles. Catherine de la Roche noted in her Venice report published in the same issue of Sight & Sound that she "doesn't understand Japanese and has very little understanding of Italian". Moreover, the festival also typed the director's name as "Achira Curosawa" (should be "Akira Kurosawa"), an apparent carryover from the original promotional material.

So de la Roche had to pay attention to its astonishing texture at the formal level. She pointed to composer Fumio Hayasaka's innovative re-creation of Ravel's Bolero; she also praised Kazuo Miyagawa's breathtaking photography, which drew attention to the forest's In the scene, he presents "the state of sunlight penetrating the leaves, showing all the patterns that are naturally formed. In this, we witness the movements of the characters, their faces and hands, all of which constitute a very convincing beautiful, beautiful picture. Because of this, in my opinion, Rashomon is indeed the supreme example of sound film. Its picture narrative maintains its own continuity and continues to strengthen. Its image and sound Together, but not interrupted by the sound."

When "Rashomon" was released in the United States, it was subtitled in English. Because of this, critics in the United States are better equipped to evaluate its narrative innovation. Henry Hart wrote in the January 1952 Film Review that what stood out about the film was "an insight into the human heart. It was enough to shame Western psychoanalysis. We can realize that the forest incident That different version of the story either amplifies or protects the self-esteem of the narrator. The basic thesis of the film is that the Japanese are asking the world: 'Who knows who is guilty? Who is the innocent in this terrible event? 』

Writing in the New York Times on December 27, 1951, Bosley Crowther commented on the film, stating, "It's a unique, exotic work of art, and it's hard to put it together. Compared to a traditional feature film,” he also asked, “is the film relevant to the contemporary era? Does its depressing cynicism, and ultimately the way it grasps hope, reflects current Japanese nationality? ? We may not be able to tell you that."

It may be easy to forget that the West had adapted this film in 1964, and that was 1964's Rashomon of the West, a work directed by Martin Ritter. Paul Newman played the bandit, Claire Bloom played the victimized woman, and Edward G. Robinson served as the narrator. Most people may also not realize that Akutagawa Ryunosuke's original material has been repeatedly remade in Japan, such as Sato Shoubao's "The Secret of Kusama" (1996), Miyake Kenki's "The Mist" ( 1997) and Tajomaru by Hiroyuki Nakano (2009).

However, even people who haven't seen Akira Kurosawa's films are likely to know the psychological term "Rashomon effect." It describes unreliable eyewitness accounts of conflicting accounts of certain events. Any competent director, critic or screenwriter will know how Hashimoto's groundbreaking narrative techniques have widely influenced Quentin Tarantino's Pulp Fiction (1994), Brian Singer's The Usual Suspects (1995), Richard Linklater's Tape (2001), and Zhang Yimou's Hero (2002), as well as tons of TV shows.

After all, this is a post-truth era where the lines between subjective experience and objective facts are increasingly blurred. Isn’t this the perfect time to revisit Rashomon?

View more about Rashomon reviews