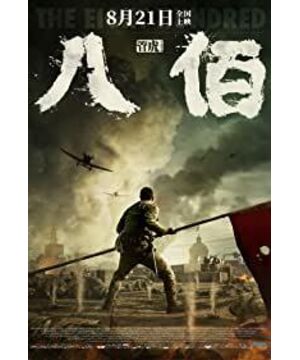

Contemporary video works are filled with a large number of similar creative phenomena , which is really distressing. Because for discussion it means that the same words and ideas have to be repeated. For example, "Eight Hundred", like many popular works in recent years, is technically excellent, and the scheduling is very gorgeous, but the structure has the problem of overhanging warts. As a result, it ended up in a mixed state similar to many of the contemporaneous images - it seems I've been talking about too many of these mixed works during this time. Not to mention the strengths and weaknesses of "Eight Hundred", which have also appeared in the views I once advocated. When I keep repeating what I've said, I get bored.

From ancient times to the present, genre creation has always sought a commonality of change. The different order of assembly of the same elements can make works with similar themes produce different meanings and trigger different emotional feedback. If supplemented by in-depth stylized design, it will form a completely different appearance from similar works and stand out. We can clearly judge whether these elements are unique or square, all based on the basic completion of the film. Therefore, although "Eight Hundred" has an ill-fated fate and was obstructed by an invisible hand, it still maintains a considerable integrity when it is released, and there are conditions for discussion on the work itself. However, speculation on the impact of the off-site does not stop there, otherwise it will fall into a cycle that is difficult to falsify. Even though the second half of the film is full of scissors and very dilapidated, its main problem—splitting—is the style and structure of the film itself.

This was supposed to be a war movie with a strong personality, but unfortunately, the aesthetic style painstakingly created in the first half of the film quickly disintegrated in the second half. I once praised Guan Hu's "The Eve" in "My Motherland and Me". This short film is a brilliant genre creation, full of narrative driving force, and the scene scheduling is from the simple to the complex, which is fascinating. Even though "The Eve" and "Eight Hundred" are very different in theme, they are both depictions of real historical events, and the overall tone and background are basically the same. In fact, as a war movie that chose a rare angle to cut into, "Eight Hundred" shows its great viewing value and historical significance, but it cannot become a masterpiece due to the fragmentation and dissolution in style.

"The Eve" revolves around the flag raising at the founding ceremony, showing vigorous dramatic tension. Ironically, "Eight Hundred" is divided into two parts in the paragraph of raising the flag, and there is a clear distinction between outstanding and boring. And this episode itself, due to ideological reasons, has all kinds of cohesion problems and overly exaggerated expression techniques. But in general, the flag raising is still a pretty good climax of the film. Although from the real situation, this battle is basically fictional, but the emotion is very complete. In the paragraph of raising the flag, the contradictions of several characters are resolved at the same time, such as Ou Hao's exit, Wang Qianyuan's transformation and so on. In addition, it is directly related to the end of the film, leading to a series of actions of the Japanese army and the Yao warriors.

Therefore, I have reason to think that raising the flag as a dividing line is an intentional approach of the film. But it ends up separating the emotions of the film before and after, while structurally splitting the film in half—if that's the case, then that's the film's biggest flaw, and I don't know what it means.

The 2018 French film "War" shows a suffocating sense of presence, which is another image expression that is different from traditional narratives. This expression abandons the principles of classicism, has nothing to do with characters, has nothing to do with perspective, doesn't even care about cause and effect, does not care about the emotional ups and downs of the audience, and the camera maintains a very active sense of participation. It creates a vague but gritty image throughout, engulfing it in wobbly handheld photography and inescapable confrontation scenes. In the fierce rhythm, "War" achieves a rare, novel and compact narrative effect, which is an extreme realism writing. The rationality of doing so lies in the natural high-intensity figurative display of images, as well as the enormous energy contained in this display itself.

Another French film from last year, Les Misérables, has a similar idea. Although it does not construct the most extreme presence like "The War", the stories that take place on the streets also keep the camera in a hands-on attitude. It's not just because of a lot of handheld photography, but also the editing, acting and sound.

The first half of "Eight Hundred" is similar to the street part of "War" and "Les Miserables". Movies don't give us time to fully understand each character, but rely on their instantaneous state to show a certain personality. The Sixing Warehouse is a closed space, and the situation of the warriors who are trapped and fighting is vividly presented through complex and complicated scheduling. Introductory scenes in traditional narratives are no longer important, even redundant. In an instant, we are forcibly drawn into the battle, and we experience several moments of life and death with the characters, revealing once again the importance of the image itself as a display. At this time, every picture was pierced into my bones. It was a scene of war that did not need to be explained, just presented a war scene with abundant energy. If it is defined as patriotic education, then I am willing to accept it and be moved by it.

At the same time, the rough handling of group images becomes no longer a problem, because in extreme presentation, the moment the image appears, it will provoke us to establish a psychological recognition. These characters can be seen as tools, pawns, and stereotyped characters that become flaws in traditional narratives. But placing them in a situation like the Sixing Warehouse is justified. Individual soldiers in war are already at the mercy of their own hands. And this explosive presentation, which only focuses on the scene, is obviously different from the real documentary images. Even through certain dramatic techniques and montage passages, the fictional situation exudes an even hotter sense of documentary, approaching a certain kind of authenticity more efficiently. It provides us with a shortcut to history, and even if it is a man-made hypothetical historical fact, the emotions that are concentrated and distilled are undoubtedly real.

Sacrifice itself is used as a display spectacle, and it is constantly beating our hearts. In essence, such a display is indeed a rough and direct sensory stimulation, trying to mobilize the audience's physiological response, but unlike those special effects spectacles, its roughness comes directly from our general cognition of human nature. Without knowing Chen Shusheng's background, inner changes and emotional motives, we can still be moved by his suicidal sacrifice, which is the emotional projection caused by the aggressiveness of the camera. In this section of the presentation of "Eight Hundred", although it has a soundtrack, it still deliberately avoids false heroic depictions. Chen Shusheng and the soldiers who jumped off the building in line behind them did not use those vulgar upgraded shots to emphasize their faces and exaggerate their tragic and solemnity. Instead, they showed death neatly without interfering with the narrative time. Again, the display itself has enough energy.

Even though the tight fighting scenes in the first half of the film, like other war films, frequently invoke the most extreme methods of violence, the audience is inevitably plunged into fiery emotions: continuous explosions, black blood, terrified shouts and flying limbs ... The dirty and cruel display method it deliberately highlights proves that this kind of image is far from making people's blood, satisfying curiosity or refreshing feeling, but conveying a clear critical meaning through the image itself. The anti-war connotation is born from this, from the camera's unadorned and detailed confrontation of the war itself, rather than exhortation through dialogue or subtitles. For me, in the face of such a powerful expressive force, the flatness and out-of-focus of the group portrait will not hinder my experience, the reaction to the event has gone beyond the substitution of the character, the character and its destined destiny as an attraction. elements, have been fully integrated into the extreme atmosphere.

If "Eight Hundred" "goes all the way to the dark" in such a high-intensity display, I will applaud it. Not to mention the defense of the Sixing Warehouse, no matter what the historical facts are in reality, the progressive space of the Concession - Suzhou River - Warehouse itself is a perfect stage for the movie. In addition to the warehouse, there is another symmetrical display scene that can be used, and their relationship with each other hides more aesthetic and ideological depth. But to my disappointment, after the flag was raised, the film simply returned to the traditional narrative atmosphere between the main theme and the genre industry, and all of a sudden the heavy and oppressive display energy created before was completely dissipated. .

What's more, the narrative level of the second half is far inferior to the display expression of the first half, full of promiscuous plots and too many descriptions of character states, and the ending has also begun to be upgraded frequently, and the sense of rhythm has been smashed to pieces. You can say that Guan Hu has not mastered the choreography of literary dramas, and is covered with various character states, but ignores the real motivation. You can say that because of the scissors, the characters have no ending, and the emotions have no foothold - did Wang Qianyuan and Xiaohubei fight the Japanese? Did you die in the end? Did Jiang Wu fire after getting on the cannon? What is Fang Xingwen's motivation? What is the purpose? How did Zhang Yi suddenly appear on the other side? Where did he run to after getting off the tram? These are not blanks, no aftertaste, just the negative effects of scissors.

What is even more twisted is that the film's scattered viewpoints before the flag raising and the shooting method that makes the characters out of focus, although the depth of the characters is consumed, but it reflects the strength of the event itself. Instead, after the flag was raised, he made a 180-degree turn, trying to re-provide the service of substituting characters. This horizontal jump in creative strategy caused damage to the style of the work. In addition, due to force majeure, lack of explanation, and even disappearance of the characters, it is no longer possible to re-describe the continuity arc, which will inevitably make the movie anticlimactic.

In any case, the essential flaw exposed in the second half of the film is that the presentation, which was ostensibly sublimated into a more precise narrative, actually shattered the previously constructed chaotic and orderly atmosphere. Too many emotional fragments, trying to get us into each character, inevitably dissipate the vague and emotional impact, resulting in a huge emotional gap. It can be said that after the flag is raised, refocusing the camera on a character, or even introducing a new character, does not bring a profound portrayal of the character, but turns emotion from arousal to incitement, which is deliberate and disgusting. The process of returning from display to description is the key to the film's loss of tension. When the focus became clear, too much unnecessary rhetorical sensationalism was added, but it was unable to make people realize it, and it was not as moving as the blurred group faces before.

This redundancy is also reflected in the use of subjective lenses, another major flaw that I cannot bear. The abuse of the subjective lens greatly affects my look and feel, and it may be more uncomfortable for me than the plot after the flag is raised. The first is the white horse. We have seen this kind of figurative romanticism in too many war films. They are often separated from the reality of the work itself, not affected by the external world, or less affected, reflecting an extreme symbol A symbolic, symbolic existence is essentially a subjective lens. The same is true for the white horse in "Yao Bai", why not choose a black horse or a brown horse? It is because the white horse is visually more holy.

In the fierce exchange of fire, the white horse basically came and went freely. Even if there were scars on his body, it was still out of the real context of the film, forming a strong visual contrast with the dirty soldiers and the surrounding ruins. This makes it a synthesis of spirituality and divinity, an emotional incarnation that is free from the fire of war and cannot be destroyed. Therefore, the first layer of white horse imagery is ready to emerge, which is the usual thinking of every war film director: the ugliness and despicability of war are contrasted with the purity and beauty of life. Especially when this kind of beauty is tainted, people will naturally have a disgust for war. But I think that the meaning of the white horse will stop here, and it is very reluctant to speculate whether it reflects any national sentiment, what kind of righteousness of the family and the country and the brilliance of human nature.

What's more, the image of the white horse was placed in "Eight Hundred", which was originally a superfluous romanticism. Because the battlefield symbols established in the first half of the film mix high-density documentary with a heavy atmosphere created by fiction, there is no sufficient room for surreal imagery to be displayed . We only need to focus on the soldiers' faces, actions, objects on their bodies (family letters, photos, suicide notes, shadow puppets), and the establishment of their interactions and relationships, which completely covers everything that Baima is trying to express, but it is not enough in terms of perception "clean". In addition, there are the feasting concessions on the other side of the Suzhou River, as well as compatriots and foreigners watching the war on the other side, etc. The complex viewpoint matrix has long been able to well reflect the attitude and criticism of this war, so the value of the white horse What's left? It's purely a visual design. But in my opinion, this kind of visual design is also unnecessary. In order to blindly pursue a certain kind of artistry, it indirectly destroys the centralized power of the display itself.

So, in the second half of Xiaohubei, when I reunited with the white horse, fed it, and depended on it, my mind was full of the scenes of "Wild Horse with a White Mane". To say that the horse is such a romantic animal, it shows its true spirituality, its vitality, and all its charming charms. So far, no one can surpass "Wild Horse with a White Mane". In short, the white horse in "Eight Hundred" is a superfluous image element. It is probably just to use a romantic metaphor to flaunt an outdated formal grammar, but it is also too common and lacks novelty.

What makes me feel more discordant is the two scenes of pure psychological activity in Xiaohubei after his brother's sacrifice. He imagines the Dragon Boat Festival played by Ou Hao as Zhao Zilong, who is seven in and seven out. It seems restrained to appear only twice, but even once, it seriously hurts the overall ideographic effect of the film. And these two psychological activity scenes, in terms of special effects and modeling, are relatively rough and clumsy, and there is a reaction that destroys the overall tonality. It is necessary for me to reiterate my point of view for the hundredth time, that is, Mitri's description of the objectification of subjective consciousness: for movies, purely psychological scenes are basically not valid, and most of them are made by the director. Because such lenses allow the concrete image to distort the perceived elements of the imagination, thereby violating the psychological characteristics of the imaginative activity.

Therefore, the "objectification of subjective consciousness" in film is a dead end. The way of its representation determines the objectification and flashback shots that can only express the subjectivity of objects and the whole of purely imaginary things. These methods are either in line with the protagonist's vision and mood, or can make the fantasy content form a homogeneous whole, eliminating the insurmountable psychological barriers from reality to non-reality. Either it conforms to the realistic representation of objective content and does not violate the psychological characteristics of recall. Based on this angle, I have always been very sensitive to the subjective lens, and it is difficult to really fit the language of the film. And the very few directors who use the subjective lens well are basically masters who will go down in history.

Many people have analyzed the progressive relationship between the concession - Suzhou River - warehouse. This kind of environment naturally provides a kind of dramatic tension, which contains the psychological state of people on both sides of the Taiwan Strait, the difference in landscape and the process of the eventual intersection. Compared with the triple definition of "watching" that many people say, and the estrangement of status, culture and psychology implied by spatial differences, what I am more interested in is that Commissioner Huang Xiaoming used an alternative way to break the first stage after his appearance. Four walls. Of course, this little treatment can't save the collapse of the latter part of the film, but it does make me smile, and my thoughts fly with it.

When the footage of the film turns to the bustling opposite bank, the people in the concession are the audience, watching everything on the opposite bank with binoculars and cameras on the riverside, on the balcony. And we are the audience of this audience. At the same time, the eight hundred warriors in the battle will also look to the other side of heaven. This intricate viewing relationship will definitely create a rich and charming semantics. But in essence, the warehouse is still the only stage, except that the actors inside will occasionally face the audience. The people in the concession are not only the audience, but also the actors. They connect us outside the screen with the actors in the warehouse in various senses, such as identity, action, text, structure, on and off the field. Those who live in the concession will inevitably exert their initiative, such as Yang Huimin, Daozi and other people who have crossed the shore. From the perspective of the film's expression, this is an interactive metaphor that breaks the boundaries of the screen.

At the same time, as the audience in front of the screen, the audience watching the concession and the soldiers of the 524th regiment, we have become a progressive relationship that is separated from the text and can only be reached by images. The difference is that the audience in the concession eventually participated in the performance, but we had no way to really experience it, and we could only watch them on the "other side (screen)" throughout the whole process. Thus, this sense of powerlessness and pure passive viewing leads to the question: How should we look back on this history? How will this story relate to the present, and how will it affect us as individuals?

Therefore, whether it was the creator's explicit intention or not, the line spoken by Huang Xiaoming (not to mention the performance) became the only finishing touch in the second half. This dead-end battle, as a political performance, was a battle that was abandoned at the outset and full of meaningless sacrifices. As a result, the huge and absurd nature of the war is immediately revealed, and this passage seems to be said to us in front of the screen. It seems that through the word "performance", it reminds us of the blocking relationship between real history and processed facts. But this absurd performance finally became meaningful because of human nature. The sacrifices of the strong men made the compatriots in the concession, foreign soldiers and international journalists empathize and lend a helping hand. At this time, the image penetrates time and space, evoking our empathy with history.

But because of the style and structure of the film, this feeling didn't end there. If the front is a fiction that transcends reality, then the latter is a return to the illusion itself created by the drama, losing the emotional connection with the real past. In the face of the cold and cruel history, the film failed to become a summary and reflection, but only played the role of leading the way, abandoning the possibility of in-depth exploration.

In the end, under the coercion of various ideologies, in the display of its enormous energy, in the reconstruction of the dialectical relationship between seeing and being seen, in the anticlimactic structure and in the subjective lens of discord, I had to view the film as a film. As an intermediary looking back at history and mourning for the nature of the event itself, it cannot be regarded as the end point of expression, leading to a deeper historical reflection.

View more about The Eight Hundred reviews