Color as a background of the times

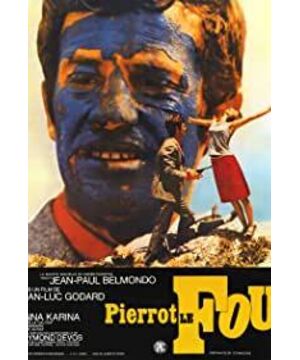

Godard, who tried painting at a young age, is undoubtedly a color genius among directors, but the classic blue, white and red of Pierrot the Madman was born in the noisy 1960s, and the use and distribution of these colors have multiple meanings.

It's an atypical crime film intertwined with eroticism, and even compared to the anti-war marches in the Western world in real space, the story seems "empty" and aimless.

The protagonist Ferdinand leaves her high-society wife, gets involved in a criminal activity, and then flees to the south, living a kind of life with Marianne Love utopian life. And Marianne's "brother" Fred is the head of the gang. Marianne gradually got tired of the nihilistic life after fleeing. One day she suddenly disappeared and joined Fred's criminal operation. Ferdinand, whom Marianne called Pierrot, finally found out that Fred was not her brother, but her true lover, who lost his love. In desperation, he shot and killed Fred and Marianne, before committing suicide with explosives strapped to his body.

In France in the 1960s, Sartre's existentialism occupied the mainstream position in the ideological world, and a wave of philosophical thought swept across Europe. His advocacy of "absolute individual freedom accompanied by absolute responsibility" influenced the spiritual thinking of this generation. Godard, on the other hand, did the opposite and chose the notorious French serial killer and public enemy Pierrot Loutrel—his real nickname is "Pierrot the Madman"—as the nickname for the protagonist who is idle and doing nothing in the story. , seems to be provoking the so-called "responsibility for one's own free choice". The combination of the names of the two protagonists also produces a layer of irony: the French goddess Marianne betrays the murderous French public enemy number one, Pierrot.

It was still France in the 1960s. After the Algerian war that lasted for seven and a half years, Charles de Gaulle recognized France's "weak position" in military, financial, material and moral terms, and finally recognized Algeria's independence. In the confusion of "defeat", Gaullist France turned to a "consumer society". At the same time, France was also experiencing the "Golden Thirty Years" (1945-1975) of rapid economic leap. People were satisfied with the growth of materials and commodities. Perek's novel "Things, Chronicle of the Sixties" is the proof of the collective psychology of the growing material desire and the emptiness of the core in this consumption age. However, Godard did not choose to depict a "majority" and "average" as shown by sociological data to represent the spiritual outlook of this society, as Perek did. The life chosen by the madman Pierrot could not make the great Most people feel the same way.

So, is Pierrot the Madman, with so many political and factual elements, a film involving politics? Was Godard's message through Pierrot's death political or apolitical? Is his political stance coherent? Is this a film of pure realism or pure aesthetics? These questions may help us better understand this "exceptional" film.

Landscape, Symbols, and 'Problematic Elements'

This scene under the monochromatic filter (Fig. 1) turns Ferdinand from actor to audience. Ferdinand went to a high society party and found that everyone was speaking mechanical language like commercials. Godard uses a monochromatic filter to transform Brecht's "distancing theory" in this scene - a scene that becomes a scene within the film, defamiliarizing the advertising that everyone is accustomed to , the requirement for actors is no longer to integrate into the role well and integrate into one "fake the real", but to hope that they keep a distance from the role. In this scene, the effect, in a nutshell, is to let the audience calmly feel the emptiness of advertising rhetoric and the hypocrisy of middle-class rhetoric. It's as if the characters in the film are actually living in what Guy Debord defined as a "society of the spectacle": "The spectacle is the moment when the commodity succeeds in completely occupying social life. Our connection to the commodity is not only visible, but our Only this connection can be seen: the world we see is the world of this connection.”[1]

In addition to the satire of the commercial society from an observer's point of view, the film is also full of commercial symbols, and TOTAL's trademark has become a landscape that can be seen everywhere on his way to escape. People who are unfamiliar with France may not know that TOTAL is the world's fourth largest oil and gas company headquartered in France. Pierrot killed a staffer at the TOTAL gas station, drove away and burned the car. I sat under the TOTAL tanker in a garage and read comics again. The presentation of TOTAL seems unclear, it just becomes the scenery in Pierrot's "journey", which directly points out such a world reality: the escape from the commercial society can't really get rid of the ubiquity of its physical space . This is where Godard comes closest to the truth of the world - he does not choose the material for the film, or rather, he deliberately retains those relatively heterogeneous parts, an art film that expresses nihilism, or even a film Should crime movies be completely stripped of commercial symbols?

Lyotard once proposed the idea of "non-movie" (translated as anti-movie, acinéma), he believed that the film should not delete or expel any elements that are useless to the plot to achieve a unified form, but should be random It does not identify and appraise the elements that are beneficial to the development of the plot, and even retains "problematic elements"[2], and pursues "sterility" and "barrenness" (stérilité), which are contrary to the logic of the production efficiency of commercial society. Godard's expression undoubtedly fits this concept of Lyotard. Commercial signs are like trees and rivers, and they have become the most real natural background of this society. The world itself is not laid out and displayed around people's activities. The subject status of people has been questioned in Godard's films. In Godard's eyes , "What is important is not to describe people, but to describe what is between people" (il ne faudrait pas décrire les gens, mais décrire ce qu'il ya entre eux) [3].

Godard's red: "It's not blood, it's red!"

Red is the most striking color in Pierrot, it may represent violence and blood... What is the aesthetic significance of Godard's "red"?

The first is about the redness of the car. When Pierrot and Marianne drove away, they did not look like criminals eager to hide. The neon lights of the car roamed the road in the middle of the night, "without worrying about leaving traces that can be traced"[4], Those lights flashed by, uncaptured. Godard said that the reflection of light on the windshield is recreating what we feel as we drive through the streets of Paris at midnight, the impression left in our minds by the traffic lights, and in short, reality. [5] The evanescence of neon lights comes from the reality that can only be observed when "lazy" and "leisure", rather than the rhythm of a fast-moving movie.

Marianne is also wearing a red dress in a scene in a walk in the woods, Pierrot looks at her red back and sings, "Your hip line", while Marianne sings "Look at my short lifeline". In this scene, the actors seem to break away from the director's arrangement, walk through the woods, and sing aimless and illogical lyrics one after another, and we once again forget about their "outlaws" their identities, and gradually forget their purpose of living in the next step in the movie. Writer Wang Anyi often says in Fudan's creative writing class: Fiction should have an inner logic. If Pierrot the Madman was a writing class assignment, it would have made her a big hit.

Marianne's dress was later used as a rag to wipe the blood of dead gnomes (in fact, red paint), and the criminals covered Pierrot's head with it, and forced him to tell Marianne's whereabouts by waterboarding. Does red represent physical violence? The answer is uncertain, as the camera then turns to Ferdinand's monologue as he walks through a deserted place, repeating the somewhat poetic lines: "Blood, I don't want to see it", "Ah, what a bad five o'clock" .

The break in the plot and footage shows Godard's reluctance to express coherent, unified thought. If the purpose of art politicization is to express appeals and to convey anger towards reality, then to achieve this purpose, it is reasonable to maintain the coherence of ideas and lines - "If the characteristics of engaging in politics mean devoting yourself to and striving for logic Rigorous system of views and appeals... Godard shows the opposite of intervention."[6] Godard's response was ": In Pierrot the Madman, the only unité is emotional." [7], we could not find a consensus and unity in political demands. In other words, Godard does not believe that the expression of art can directly achieve the effect of political demands.

Politics in Pure Poetry

Questioning whether Godard really intervenes in politics is based on such a logic: mimésis in Aristotle's sense, meaning "the art of imitation", they believe that through art, showing a heroic protagonist can guide People imitate or avoid certain actions in the play to achieve a "pedagogical" effect, they believe in a direct cause and effect relationship, that is, the artist's intention can be communicated directly and accurately to the audience, outline for the audience An accurate and unmistakable portrait of the struggle of the masses [8].

Godard believed in the effects of mimésis, but at the same time questioned it. The most political scene in the film is the part where Pierrot and Marianne perform the Vietnam War, where Marianne paints a yellow face to play a Vietnamese girl, and Pierrot uses matches as a bomber. Godard said that the scene of this satirical Hollywood blockbuster is shown out of "pure logique", like a child imitating the police to catch a thief (comme lorsque les enfants jouent aux gendarmes et aux voleurs). [9] In other words, Godard believed that the mechanism of "mimésis" would have a certain effect, that the games of the children's world were repeating the rules of the adults' world. However, Godard also questioned the essence of the function of "imitation": can "real guns and live ammunition" and such a realistic war movie allow people to learn the lessons of history and distinguish "what should be done and what should not be done"? Or are films like this just a kid's play, in which we're just reinforcing the "ruler" and "oppressed" stereotypes? Marianne's face painted yellow is not Godard's stereotype of the yellow race, but a single stereotype of the "oppressed" that Godard is imitating, which Hollywood blockbusters will eventually create.

Is the real purpose of the politicization of art to portray identities as planned according to hierarchy and order? "It's not blood, it's red." What Godard's words want to say is that it seems that we have naturally given the meaning of "blood" to red. Godard wants to use the film to "reform" the usage of such symbolized words, disrupting the meaning of these words by social consensus (such as red symbolizes violence). This idea fits Rancière's definition of "aesthetic system" (régime esthétique) of politicized art: "to re-see what has been seen, to re-establish relations that once did not exist, in order to perceive the perceptual coherence and emotion of The dynamics of production fractures” [10].

What Godard wanted to do was to produce an "image totale", against the "system of images" (système d'images), "the totality of images" (une totalité des images) [11]. This system of images, the totality of images, is the logic of capitalism and the Soviet system: images of commercial or political propaganda are encoded by the collective consciousness they want to promote, occupying the stage and screen that spreads to all societies. It is in this sense that Godard's depolitics becomes "politics".

Godard throws us a question: why do we demand that a film must be purely political, not purely aesthetic, purely poetic? If a film is purely poetic, does it instantly lose its political undertones? Pierrot's monologue writing in the film may provide an answer: "The writer chooses...the freedom of others" and "language is born from the ruins". Roland Barthes in "The Preparation of the Novel" called this kind of atonal babble "Album", which is contrary to the continuity of private diaries and runs counter to "totality"[12], in other words, it is Godard's pure poetry was born from the ruins - the fragmentation of positions, the fragmentation of actions, and the ambiguity of intent.

It is through this purely poetic expression that Pierrot the Madman abandons the language set by the collective unconscious encoding in the consumer society, and thus becomes the opposite of films that use this language to intervene in politics. Godard's blood, or red, represents the total other, outside of him, not in it. He played children's imitation games, and he was wandering among the ruins to write poetry of independence. The non-politics of Pierrot the Madman is also a kind of politics.

[1] Guy Debord, La Société du Spectacle, Paris, Gallimard, 1996(1992), p.24.

[2] Jean-Francois Lyotard, Des dispositifs pulsionnels, Paris, Édition Galilée, 1994, p.57-59.

[3] «Parlons de "Pierrot", nouvel entretien avec Jean-Luc Godard», Ca hier du cinéma, n° 171, octobre 1965, p.25.

[4] The original "sans souci de traces ou de récupérations", see «Fable sur "Pierrot"», Ca hier du cinéma, n° 171, octobre 1965, p.36.

[5] «Parlons de "Pierrot", nouvel entretien avec Jean-Luc Godard», Ca hier du cinéma, n° 171, octobre 1965, p.35

[6] Rémy Rieffel, La tribu des clercs. Les intellectuels sous la Ve République , Paris, Calmann-Lévy/CNRS, 1993, p.226-241

[7] «Parlons de "Pierrot", nouvel entretien avec Jean-Luc Godard», Ca hier du cinéma, n° 171, octobre 1965, p.25

[8] See Jacques Rancière, Le spectateur émancipé, Paris, La fabrique, 2008, p.64

[9] «Parlons de "Pierrot", nouvel entretien avec Jean-Luc Godard», Ca hier du cinéma, n° 171, octobre 1965, p.25

[10] The original text is: faire voir autrement de ce qui était trop aisément vu, de mettre en rapport ce qui ne l'était pas, dans le but de produire des ruptures dans le tissu sensible des perceptions et dans la dynamique des affects. Jacques Rancière, Le spectateur émancipé, Paris, La fabrique, 2008, p.72

[11] See Georges Didi-Huberman, Passés cités par JLG. L'Œil de l'histoire, 5. , Paris, Éditions de Minuit, p.107

[12]Roland Barthes, La préparation du roman , Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 2015, p.440

View more about Pierrot le Fou reviews