By Ben Thompson (Sight & Sound)

Translator: csh

The translation was first published in "Iris"

In 1989, Richard Linklater met a woman at a toy store in Philadelphia. They traveled all over the city together and had deep conversations until late at night. For Linklater, the only thing that kept him from fully immersing himself in the encounter was the thought that "maybe it could be made into a movie."

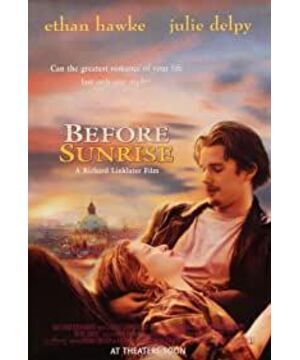

Now, it's really been made into a movie. This Love Before Dawn (1995), like his two previous films, focuses on a time span of less than twenty-four hours. However, his groundbreaking mid-twenties lifestyle epic, Urban Ronin (1991), featured more than a hundred characters; his hazy but perceptive high school memoir, Young Man (1993) Twenty-odd characters were dealt with—however, "Before Dawn" focuses on just two characters, which he "puts under a microscope and sees what happens."

The film is set in Vienna, which, according to Linklater, “is a lot like Austin — the coffee shop is full of smart people, but they don’t know what to do next.” "Love Before Dawn" further interprets the theme he loves - "the untrodden road". Jesse — a tall, skinny, European complaining American, played by Ethan Hawke — tries to convince Celine, a bright French student played by Julie Delpy, to get off with him. In his view, this will prevent them from constantly thinking about this moment and thinking about what would have happened if they had done so for the next two decades.

In Ronin, Linklater's unpredictable shots are always trying to meet some new friends. In this film, he chose to keep the camera on them - although there are still potential distractions, such as the quarrelsome couple on the train, a German avant-garde troupe, which seem to provide more Lots of dramatic rewards.

According to tradition, on-screen romances are fast. And in this film, Linklater slows it down, which at least provides the viewer with a sense of real-time. This has proven to be a productive technique that presents a remarkable ambiguity, whether in the relationship between the characters, the relationship between the audience and the actors, or the relationship between the audience and this type of film, All exhibit this characteristic.

We see a series of romantic passages—a chance encounter, an encounter with a gypsy fortune teller or a street poet—but we eventually realize that they may be very different from the kind of love scenes we imagined. When Celine and Jesse split, the camera revisits all the places they've traveled. All of this was overshadowed by their absence, we found.

"Love Before Dawn," which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, established Linklater as a pioneer of American independent filmmaking. While the film is actually—like its predecessor, The Young and the Wild—the product of a studio (produced by the helpful, seldom-involved Castle Rock, and the less sympathetic Universal Pictures) industry). Linklater has always been regarded as "Generation X" or the Eric Rohmer of Texas, and these classic evaluations of Linklater do not seem to reflect the uniqueness of his works. People are always used to discussing him from the perspective of "breaking" or "disengagement", but what he should be most admired should be "connection" and "participation".

Linklater is self-taught in film (he only took a one-semester course in film history at community college): "They asked me to turn in two pages of homework, but I would turn in eight." Linklater founded Austin Film Society. He is still the artistic director of the association today. His life's work is to "try to do as much as possible for the film industry that few people have set foot on." Immediately after the interview, he rushed to Berlin without stopping to receive his Silver Bear trophy.

Reporter: You don't have any formal film education, do you think it will make it easier for you to find your own style?

Richard Linklater: It's hard to articulate why you do something. But I guess my instinctive rejection of film school was because I didn't want anyone to tell me what to do. It's about authority - some teachers will say (Linklater puts on a comical, trembling voice), "Why didn't you have a close-up of the clapping?" or, "This story isn't enough, there's no drama."

Reporter: "This story is not enough, there is no drama", this kind of evaluation will cause some problems for our Linklater.

Richard Linklater: Without a doubt. If I were in a system of "mass-training talent for the industry", I probably would never have conceived of a film like this. Another reason is that I think I might be too shy - I don't want to make a movie until I'm ready.

Reporter: You have worked on offshore oil rigs for several years. Even then, did you still have the ambition to make a movie?

Richard Linklater: I probably had the idea back then. Because we were mining in the Gulf of Mexico, when I got back on land, I had a lot of free time. At that stage, I was most interested in writing and reading. But when I go ashore, I watch at least two or three movies a day. I live in Houston, and there's also a big theater that does double-movie productions: The Great Amberson and Citizen Kane, and Poor Mountain and Bad Waters and Days of Paradise. I also read a book - The Technique of Filmmaking. It's sitting on my bookshelf. I read that book every day and I thought, "One day I have to make a movie."

Reporter: Then when you get back to the rig, you must be very depressed.

Richard Linklater: Can't say the same, because I read books there. Life at sea is all about literature—Dostoevsky or something—and life on land is all about cinema.

Reporter: So for you, is there a corresponding contradiction between writing and the ambition of a director?

Richard Linklater: I think I wanted to be a writer in the first place—I grew up in Texas and that seemed like the only option, although I also played a little music. It took me a while, and watching a lot of movies, to finally realize that I might not be a real writer: I have a visual touch, I can have movies in my head, and movies are actually my calling. If I can't make movies anymore, then I'll probably do some behind-the-scenes work, or write something about the movie, or buy a theater, or whatever -- I think it's the same work anyway.

Reporter: How did you train yourself to start making films?

Richard Linklater: The start of my career should have happened in my second two years of college. So when I was twenty-two, I saved all my money. I moved to Austin with a Super 8 camera, a projector and some editing equipment and started learning filmmaking from that book - the nuances of lighting - it's a real craft, you It takes years of practice to perfect it. But the basic stuff is easy. Anyone can set up some lights to shoot a scene. I found that I liked the technical aspects of the film: I would draw the curtains and edit what had just been shot for twenty-four hours straight. I spent several years creating short films, which were really just technical experiments. Looking back, I'm amazed at how methodical I was - I would create an entire film just to work on a different lighting technique. I knew it was important that I couldn't get my films out in the first few years because I might get hit and quit the film business. Because I don't have enough skills that allow me to realize my ideas. In the end, I shot an 89-minute feature film with the Super 8, which was the culmination of this phase of work.

Reporter: What is it called?

Richard Linklater: Dead Reading is Useless. It took me two years to make this film: one year of shooting, one year of editing - and I haven't done it like that since (laughs).

Reporter: Has this film ever been shown?

Richard Linklater: We recently had a small film festival in Austin. This is my first screening of this work. Many people say that this is their favorite of my work. But it's so personal that it seems laborious.

Reporter: What is the movie about?

Richard Linklater: It's kind of like a prequel to Ronin, or a precursor to Love Before Dawn. In fact, this work mainly explores the mentality of travel. It focuses on a trip to America on Amtrak: more than half of the film was shot on the train, the rest was getting off to town and just walking around. It's like a guy -- that's me -- going on a trip with a camera and pressing a button and having the machine start filming the scene. It's very formal, the camera never moves, and there's very little dialogue throughout the film. And, because the microphones are farther apart, it sounds like mumbling. In a way, the film is also the opposite of Urban Ronin, where everyone speaks their minds exactly.

Reporter: All your films seem to have a very precise sense of history. They involve both your personal standpoint and an in-depth look at the culture. For example, Ronin is widely seen as the epitome of something, and that must have been very heartening to you as well.

Richard Linklater: After you make a movie, you have to settle with it. Because anything that happens after that is beyond your control, but it's still kind of annoying. I found myself unable to understand the kind of discussion that combined "Gen X" and "Ronin" - I was a little confused about it. President Clinton is using the word! "I don't think you are the lazy generation, I think you are the seeking generation," he said in his commencement speech at UCLA. But to me there is no difference between a lazy person and a seeker. All the people in the film have their own things to do, but they are not in a consumer culture. That's the most important sin: don't focus your life on work or shopping. I feel that people should be more aware of the scarcity of these things, and I am disturbed by their confusion.

Reporter: The irony is that some things start out as a rejection of consumer culture, but they end up in the breakdown of the consumption list - a means to sell things to people who don't want to be associated with capitalism Congruent children.

Richard Linklater: I get it, I get it, it's a very vicious cycle. Because of this, I don't want to get too involved with this thought because it's my worst nightmare. People will look at those Ronin characters and ask: What the hell happened to them? They're white, they're half-middle class kids - what else are they complaining about? All I can say is, well, in this "money is everything, we should all capitalize" culture, its opposite is so marginalized, it really makes me sick. I think that's what they're complaining about: they're complaining about everything that happened before they surrendered!

Reporter: So in "Youth and Madness," did you try to provide some historical perspective?

Richard Linklater: That's important because I don't think people are adapting anything. Because of this, all these "intergenerational" discussions are downright fallacies. It's just a demographic: you have to make people feel different when you're trying to sell to others. No one is going to say, "You know, people haven't really changed." But people were like that in the seventies, even in the fifties. It's just that the drugs they take have changed. Therefore, the idea of "Youth and Madness" is of course coherent with "Urban Ronin". The former was set in 1976 - when people had long hair and music was long.

Reporter: It's interesting that people rebelled against radio rock as a whole, which now seems like a great thing.

Richard Linklater: Yeah, it was all about, "What kind of company rubbish is this, they make us want to vomit!" Looking back, I found a certain kind of energy, and I used that Push the film. Music plays a major role in the movie.

Reporter: How did you achieve this? Did you also decide on the soundtrack when arranging the film?

Richard Linklater: Sometimes yes. It's intuitive: I wake up every morning with a new idea, like a song that could be used somewhere. I probably think about half of the soundtrack before I start shooting, and the other half comes out during the shoot. I knew it was okay to start with "Honey," and when they walked into the pool, the audience could hear "Hurricane." When Mickey was beaten, it was "Mr. Not a Good Man". I love the irony in the lyrics, even if some of them are too obvious - like "The Holidays Are Coming."

Reporter: That's normal, isn't it? It's very rare for a teenager or a teen to say, "I'm not going to like this song -- it's so similar to my life." I think the same is true of movies, maybe when you were writing "Youth and Follies," you were very interested in that song. Bad high school movie tradition, some kind of weird idea?

Richard Linklater: Maybe everyone around me makes me think I have to make a teen movie. The film I wanted to make had to capture that energy in my memory: walking around like nothing happened, but at the same time everything happened. It's fun to dive into a genre that I know a lot about -- there's actually a lot of good high school movies out there.

Reporter: Which do you like?

Richard Linklater: My favorite of course is the "Edge" movie. "Over the Brink," "River's Edge," I'd love it if this teen movie ended in an apocalypse. Like at the end of "Over the Edge," they open fire on the school together, which is the ultimate goal of the teens.

Reporter: However, "Youth and Frivolous" mainly rests in a certain state of balance.

Richard Linklater: My films are probably more ambiguous than I imagined myself. This may not be a good enough state: the definition of stress is not clear enough.

Reporter: What is oppression? Not Aerosmith, right?

Richard Linklater: Being a teenager is depressing enough: you have to have parents, you have to have teachers, you have to live in a damn town, and that's bad enough.

Reporter: Are you worried that you may have created this generation's "Animal House"?

Richard Linklater: If I did, I didn't mean to! Some teens have watched "Freakout" fifty times and threw a party for it. They both felt that the seventies were a great era, although there are many instances of the opposite in the movies.

Reporter: Do the two actors who starred in "Love Before Dawn" match your expected image?

Richard Linklater: I had a script and I had to find two people. However, I didn't know who I really needed until I found them. If I need an American woman and an Italian man, the same goes for a role change. This kind of thing is always ambiguous. The same goes for cities.

Reporter: After you settled on Vienna, did you try to avoid paying homage to The Third Man?

Richard Linklater: Well, we shot on the Ferris wheel, but that's just because these two characters do do this touristic -- I love the word -- thing.

Reporter: In this film, it's as if the characters are deciding when and how to move on, and the structure also echoes the pattern of their relationship, which I love.

Richard Linklater: The only goal of this film is how to have the next interaction - it's always the next thing that moves you forward. In fact, they didn't realize how much they cared about each other until they finally separated from each other. We all create these romantic ideals, even if they don't exist. This human trait is still somewhat endearing.

Reporter: In the production notes, there is a very straightforward record. Julie Delpy said, "I knew that if I didn't get rough with these two American men, Celine could be drowned in these stereotyped images of women." And, in the film's lines, she describes her Situation: "It's like a male fantasy of meeting a French girl on a train, fucking her, and never seeing her again". Was it to avoid this that you had a female co-writer (Kim Chrissan) for the film?

Richard Linklater: I certainly think the film is a dialogue between a man and a woman, so it's important to find strong female writers, actresses. However, I identify with both characters pretty much - I think I share a lot of qualities with Jolie.

Reporter: "Urban Ronin" is more like crossing the river by feeling the stones, but now you have a high school comedy and a romance movie. These two movies seem to be cultivating the soil that has already been achieved. Isn't it more dangerous to dabble in old soil than to reclaim new soil?

Richard Linklater: Possibly, but these soils might also be a little neater. It's like using new technology to reclaim those old mines. I think people's opinions may be a little off: I'm not really a fan of the "Before Dawn" genre, but these films fill a huge need. I wonder if I can still meet this need, but I want to achieve this through my own understanding of things. What's fascinating about this movie, in my opinion, is that it took so long for the two to have their first kiss: people are used to that kind of story - couples meet/couples "meet" in bed right away "/Then we continue to tell the story.

Reporter: There's one scene I really like, the scene where they're in the listening room of the record store, and they're listening to a really bad love song, and you can realize that Hawke's character thought to himself, "" Am I old-fashioned enough to take advantage of this opportunity? Or should I respect this song, after all, it's so bad?"

Richard Linklater: Yes. In most movies, they're there to kiss, but no one wants to take the first step. So you can feel a wonderful embarrassment. That's what life is like, but in the movies, you hardly see it.

Reporter: Would you consider creating a film with a span of more than 24 hours?

Richard Linklater: The next film will span eighty-five years! It's a true story, based on an oral history ("Newton the Kid - Portrait of the Outlaws" by Claude Stanush). Obviously this production will be more epic in structure, but I hope it still feels in line with the moment. Telling a story in an epic way can really feel remote and exhausting. There's always a weird idea, as if you just go back further and things get bigger. But I really wanted to show the twenties in the way I imagined.

Reporter: All of your films seem to be very autobiographical, but you probably haven't robbed as many banks in the twenties, so this is a big step.

Richard Linklater: Not really, because I've always felt that it's very easy to see yourself as a criminal. I don't know what the hell I'd be doing if I wasn't a film director. But if I had to defend the crime in my mind, it wasn't that hard. So, on the surface, it seems like some kind of radical departure, and to some extent it is. But if you look at it from another angle, things are quite different. I think "Before the Dawn" also made a huge change - I hope every movie is like that, it makes you wonder.

View more about Before Sunrise reviews