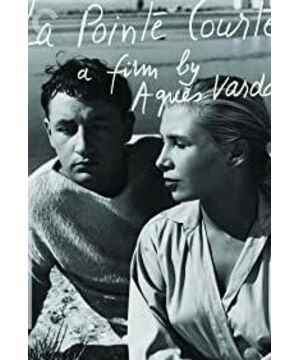

In memory of Agnès Varda, on the occasion of one year anniversary of her departure (29th March), yours truly delves into her resounding debut feature LA POINTE-COURTE, shot in a shoestring and prominently for applying an avant-garde dichotomy in its contents, altogether the film heralds the pending French New Wave movement mostly on the strength of its camera’s unbridled mobility roving around the titular fisherman’s village in situ.

The first tributary of its narrative bifurcation is an ethnological essay exploring the daily hurdles and weekend divertissements of the local folks, their livelihood (contending with policemen for fishing in an illegal lagoon nearby), their grief (mortality is high among a philoprogenitive household), their earthly concerns (a 16-year-old girl seeks the approval of her father for courtship), and their unalloyed joy (a jubilant aquatic jousting competition and its attendant festa are faithfully recorded with both intimacy and grandeur), all are enlivened through Varda’s unobtrusive regard and well-posited lens.

A second mythos that alternates with the essayist observation is a married couple’s (Monfort and Noiret) walk-and-talk across the back of beyond, to introspect the existential crisis of their matrimony, the husband is from the Pointe-Courte and the wife is a Parisienne, both are introduced a là Rückenfigur, whereas a wet-behind-the-ears Noiret looks almost angelic on top of the husband’s defiant matureness in handling the fact that his wife has fallen out of love with him, it is Monfort’s self-consciousness of her character’s incongruity and alienation with the place lingers longer in the afterimage.

Varda’s striking close-ups of the couple intersecting each other with aligned sight-lines in a rectangular angle even anticipate Bergman’s iconic similar compositions in PERSONA (1966) for more than a decade, also their conversation inside a hull anachronistically invokes a similar scene in THROUGH A GLASS DARKLY (1961). Moreover, since Alain Resnais moonlights as the editor, we can find an uncanny resemblance with his works in the conflation of its images, notably HIROSHIMA MON AMOUR (1959).

While the couple’s confessional communication leans more towards streams of consciousness, their final reconciliation with the status quo betrays Varda’s benign feminine propensity. Although the two narrative streams do not integrate as seamlessly as the film’s exalted repute implies, Varda, the filmmaker certainly made an indelible mark with this distinct juvenilia.

referential entries: Varda's HAPPINESS (1965, 8.2/10); Alain Resnais' HIROSHIMA MY LOVE (1959, 8.1/10).

View more about La Pointe Courte reviews