Excerpted from: Stavrianos "Global History: The World Before and After 1500"

As 1929 began, America seemed to be booming. The US Industrial Production Index averaged only 67 in 1921 (1923-1925 = 100), but had risen to 110 by July 1928 and 126 by June 1929. Even more impressive is the state of the US stock market. During the three months of the summer of 1929, the Westinghouse Company's stock rose from 151 to 286, the General Electric Company's stock rose from 268 to 391, and the United States Steel Company's stock rose from 165 to 258.

Industrialists, pedantic economists and government leaders all expressed confidence in the future. The financier Bernard Baruch wrote in June 1929, "The economic situation of the world seems to be about to move forward by a great margin." The heights reached appear to be enduring." Treasury Secretary Andrew W. Mellon also assured the public in September 1929: "There is no cause for concern now. This boom in prosperity will continue."

This confidence proved unwarranted; in the fall of 1929, stock market prices hit their lowest point, and a worldwide economic depression followed, the intensity and duration of which was unprecedented. One reason for this unexpected end appears to be the severe international economic imbalance that developed when the United States became a creditor nation on a massive scale (after World War I). Britain was a creditor nation before the war, but it used revenue from overseas investments and loans to pay for long-term income. Instead, the U.S. typically has a trade surplus that has been exacerbated by keeping tariffs high for domestic political reasons. In addition, in the 1920s, as many countries paid war debts, money continued to flow into the United States; the United States’ gold reserves increased from $1,924 million to $4,499 million between 1913 and 1924, or half of the world’s total gold reserves .

For several years this imbalance was offset by massive U.S. lending and investment abroad: Between 1925 and 1928, U.S. foreign investment totaled $1.1 billion a year on average. Of course, this situation ultimately reinforces the imbalance and cannot be continued indefinitely. Certain sectors of the U.S. economy, especially agriculture, suffered as debtor countries had to reduce their imports from the United States as payments came due. In addition, some countries feel compelled to default on their arrears, which has shaken some financial firms in the United States.

The imbalance in the US economy is as serious as the imbalance in the international economy, and its root cause is that wages are lagging behind rising productivity. From 1920 to 1929, workers' hourly wages rose by only 2%, while worker productivity in factories soared by 65%. At the same time, farmers' real income is declining due to falling agricultural prices, rising taxes and living costs. In 1910, the income of each farm worker was less than 40% of that of non-farm workers; by 1930, it was less than 30%. This poverty in the countryside was a serious problem, since at that time the agricultural population accounted for one-fifth of the total population.

The combination of fixed factory wages and falling farm incomes has resulted in a severe unequal distribution of national income. In 1929, 5 percent of Americans received one-third of all personal income (compared to one-sixth at the end of World War II). This means that insufficient purchasing power of the masses coexists with high levels of capital investment by those who are well-paid and well-paid. In the mid-1920s, production of capital goods grew at an average annual rate of 6.4 percent, while that of consumer goods grew at 2.8 percent. This ultimately leads to a stagnant economy; this low purchasing power cannot support such a high ratio of capital investment. As a result, the Industrial Production Index fell from 26 to 11.7 between June and October 1929, creating the Great Depression that prompted the stock market crash that fall.

Weakness in the U.S. banking sector was the last factor contributing to the stock market crash of 1929. At the time, many banks were operating alone, and some lacked sufficient financial resources to weather the financial turmoil. When one bank fails, panic spreads and depositors rush to other banks to withdraw their deposits, setting off a chain reaction that gradually undermines the entire financial fabric. This weakness in banking was exacerbated by the 1929 heat of speculation that permeated the economy, causing some firms and banks to abandon their normal precautions and engage in speculative risk-taking.

The collapse of the U.S. stock market began in September 1929. The value of the stock fell by 40% in one month, and, with the exception of a few brief recoveries in value, the decline continued for three years. During that period, U.S. Steel's shares fell from 262 to 22, and General Motors' shares fell from 73 to 8%. Every sector of the national economy suffered a corresponding loss. During those three years, 5,000 banks failed. In 1929, General Motors produced 5.5 million vehicles, but in 1931 they only produced 2.5 million. In July 1932, the steel industry was operating at only 12% of production capacity. By 1933, total industrial output and national income had plummeted by nearly half, wholesale prices of goods had fallen by nearly a third, and merchandise trade had fallen by more than two-thirds.

The Great Depression was not only incomparably powerful, but had unique worldwide effects. U.S. financial firms had to call back their short-term loans abroad; needless to say, this had all sorts of effects. In May 1931, Vienna's largest and most reputable bank, the Austrian Credit Bank, declared it insolvent, causing panic across the continent. On July 9, Deutsche Bank followed suit, and for the next two days, all German banks were ordered to go on holiday; the Berlin Stock Exchange, the Börsch, was closed for two months. Britain abandoned the gold standard in September 1931, and two years later, the United States and nearly every major country did the same.

The collapse of industry and commerce bears a striking resemblance to the collapse of the financial world; the world industrial production index, excluding the Soviet Union, fell from 100 in 1929 to 86.5 in 1930, 74.8 in 1931 and 63.8 in 1932, a total decline of 36.2% . In previous crises, the largest decline was 7%. The decline in world international trade was even sharper, falling from $68.6 billion in 1929 to $55.6 billion in 1930, $39.7 billion in 1931, $26.9 billion in 1932, and $24.2 billion in 1933. It should also be noted that in the past, the largest decline in international trade was 7%, which occurred during the crisis of 1907-1908.

These major economic changes have caused a variety of correspondingly significant social problems. The most serious and intractable is the problem of mass unemployment, which has reached tragic proportions. In March 1933, the number of unemployed persons in the United States was conservatively estimated at more than 14 million, equivalent to a quarter of the entire labor force. In the UK, there are nearly 3 million unemployed, about the same percentage of the total workforce as in the US. The worst is in Germany, where at least 6 million people are unemployed: the executive committee of the trade unions estimates that more than two-fifths of their members are completely unemployed, and another one-fifth only works part-time. France is least affected due to its balance between agriculture and industry; the country has never had more than 850,000 unemployed, although this figure does not include the sizeable underemployment in rural areas (some predominantly agricultural countries in Eastern Europe). This is even more the case in these countries, where many workers leave the cities and return to overpopulated villages, where they live with their relatives).

Unemployment on such a large scale has greatly lowered the standard of living in all countries. Suffering and poverty were widespread even in wealthy America, especially in the early stages, when underfunded private and local agencies were entrusted with relief. This was the age of queues for relief bread, soup kitchens, and veterans selling apples on street corners. Thousands of men, and even some women, "stolen trains" back and forth from coast to coast, hoping to find work, or simply because there is nothing else to do. Many more left the arid dust storms of Texas and Oklahoma for California, as described in John Steinbeck's novel The Grapes of Wrath.

In the UK, the situation was made worse by persistent unemployment throughout the 1920s. A sizable portion of an entire generation grew up with little chance and no hope of finding a job. Some painfully refer to their aimless lives as "living hell." Others gave up hope and became resigned: "Anyone has no better chance of finding a job now than winning the Irish lottery". In Germany, disappointment was heightened and tensions were heightened due to a higher proportion of the unemployed; all of which ultimately made Hitler's success possible. Perhaps most tragic is the fate of the peasant masses in Eastern Europe. Although they had always lived a subsistence life, a 1939 survey report on the Drina region of Yugoslavia, a region quite representative of southeastern Europe, revealed that among 219,279 families, 46.4% had no beds, and 54.3% had no beds. % of the households do not have any kind of toilet, and 51.6% of the households use mud as the floor. In human terms, this means that the infant mortality rate (deaths per thousand live births in a year) in Romania, Yugoslavia and Bulgaria, Greece is 183, 144 and 99 respectively, while the The infant mortality rates were 66, 55 and 37, respectively.

Social dislocations of this magnitude are bound to have profound political implications. Even America, rich in resources and with a tradition of political stability, has been filled with incredible ideas and turmoil in these years: the grant army of homeless veterans; capitalist movement; farm holidays that developed into sit-down strikes on agriculture; various proposals for redistribution of income, including the Townsend Plan that called for generous pensions; Louisiana Senator Huey Long's "Sharing the Wealth" "Exercise, wait. Another manifestation of political turmoil was the outright victory of Franklin Roosevelt in the 1932 election. The ensuing "New Deal" acted as a safety valve for political discontent, effectively nullifying extremist movements.

Political developments in Britain and France in recent years have largely been the same as those in the United States. Both countries, while battered by a political storm, managed to weather the storm within the confines of their traditional institutions. The British Labour Party came to power in June 1929, but almost immediately it ran into the problem of handing out "unemployment benefits" to the growing number of unemployed. Meanwhile, U.S. financial firms are calling back their short-term loans and refusing to consider new ones unless the U.K. government takes some savings.

In August 1931, Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald bowed to these pressures and agreed to dissolve his Labour government and lead a new National Government. This government, like Lloyd George's coalition government from 1916 to 1922, proved to be a mere facade for Tory rule, as Conservatives still had a majority in the cabinet. Although the new government was formed to save the pound, it immediately abandoned the gold standard and the value of the pound fell from $4.86 to $3.49. The introduction of protective tariffs in 1932 and preferential preferential trade treatment for imperial members was another break with the past. Three years later, an old and sickly MacDonald resigned to give way to Stanley Baldwin, so the UK actually passed the years under Conservative rule, although a coalition government in name still existed.

In France, the left was also forced to step down under the pressure of the Great Depression. The left won the election in 1932, and Radical leader Edward Herriot organized a cabinet with the support of the Socialists, as he had done in 1924. This time, the leftist cabinet was also gradually undermined by mounting financial difficulties. The Radicals and the Socialists were irrevocably divided over how to deal with the economic crisis. Helio was only in power for six months, and the other four prime ministers subsequently abdicated in a short period of time.

In December 1933, the final battle came with the revelation of the Stavsky scandal; Stavsky was a Russian-born French citizen who, together with a local pawnshop, issued deceptive bonds and, according to rumours, many important Officials and politicians have been implicated in the case. Far-right groups took the opportunity to stir up riots in the streets in an attempt to overthrow the republic itself. Although they failed to do so, they did force the cabinet to resign in February 1934. A number of Conservative cabinets have come to power, but none can cure the country's fundamental ills.

Even more dramatic and fateful was Hitler's rise to power in Germany. The Great Depression also directly and decisively affected the course of political events in this country. In 1919, with the official adoption of the Weimar Constitution, a Western-style republic was established here. In its first year, the new republic had to deal with the communist uprisings in Bavaria and the Ruhr, in addition to the monarchist Kapp's rebellion in Berlin. Unrest continued until 1923, when French and Italian troops occupied the Ruhr in a dispute over reparations. At the same time, inflation swept across the country, wiping out savings at all levels. Only because of the agreement of the Dawes Plan in 1924 and the withdrawal of French and Italian troops from the Ruhr did Germany finally begin to settle down. In the years that followed, Germany accepted the Locarno Pact and joined the League of Nations, and its economy continued to improve thanks to a large loan from the United States.

The Great Depression hit Germany particularly hard, leaving two-fifths of the workforce unemployed and another fifth working part-time only. The government at the time was a center-left coalition, led by the socialist Chancellor Herman Miller, and the old conservative war hero Paul von Hindenburg as president. Like socialist cabinets in other countries, Miller's cabinet in Germany was gradually undermined by arguments over how to address unemployment and other problems caused by the Great Depression. The left favors increased unemployment benefits, while the right insists on cuts and a balanced budget. The latter approach is supported by most economists because the rationale for deficit financing has not been worked out, either in theory or in practice. In March 1930, Miller's cabinet was forced to resign, and since then Germany has been ruled by both centrist and right-wing parties.

At first, a coalition government was organized by Heinrich Brüning, a ruthless, stern but intelligent, upright member of the Centre Party who earned respect rather than friendship. The tragedy of this well-meaning patriot is that he dug the grave for German democracy. Lacking the support of a majority in parliament, he turned to Article 48 of the constitution, which empowers the president to issue decrees in times of emergency, which have the force of law unless explicitly rejected by a majority of the National Assembly. Indeed, the National Assembly did vote against the original emergency decree, but Bruening fought back by persuading Hindenburg to dissolve the National Assembly and order new elections in September 1930. Bruning expects various parties from the centre and the right to win an election majority, allowing him to run the country in a formal parliamentary fashion. The election, however, showed that Hitler's National Socialist Party had emerged as a national force.

Adolf Hitler, the son of a minor Austrian customs officer, had gone to Vienna in his early years aspiring to become a painter. Lack of talent, he subsisted on the most humble jobs of all kinds and lived a miserable life for five years - which, by his own account, seemed exaggerated. His tragic circumstances - real or imagined - along with unquestioned professional failures, help to explain the ardent beliefs he acquired at this time: hatred of Marxists and Jews, hatred of parliamentarism regime that despises the wealthy bourgeoisie and its "decadent" culture. Hitler wandered from Vienna to Munich, where he served in the Bavarian regiment in 1914. Although he fought bravely in the war, was wounded three times and was awarded the coveted Iron Cross, he apparently showed no special talent, for despite his dedicated service he was only promoted to corporal. However, these years in the army were the happiest of his life, and military training provided him with the ability to discern directions that he had always lacked.

After the war, Hitler turned violently against the New Weimar Republic. "I don't think the present Germany is a democracy or a republic, but an international pigpen for Marxists and Jews." The leader of the party, the head of state. After a series of inflammatory speeches about nationalism and anti-Semitism, he joined Field Marshal Ludendorff in a burlesque opera-style riot in Munich in 1923. The riot was easily suppressed by the police, and Hitler was imprisoned for nine months. At the time, he was 35 years old and in prison he wrote Mein Kampf — a flamboyantly lengthy autobiographical memoir in which he vented his hatred of democracy, communism and Jews, detailing How can a defeated Germany become "the monarch of all mankind". "Racial purity" was the key to this victory: "A nation committed to cultivating its best racial elements in an age of racial poisoning will one day become the monarch of all mankind."

After his release from prison, Hitler continued his agitation work with disappointing results. In the December 1924 election, his Nazi party won only 14 seats and 908,000 votes, and in the May 1928 election it won even fewer - 12 seats and 810,000 votes, i.e. 2.6% of the total votes. The September 1930 election was a major turning point, when the Nazi Party won 107 seats and 6,407,000 votes, or 18.3 percent of the vote. These snowflakes of votes did not come from workers, as the Socialists and Communists won 13 more seats in 1930 than in 1928. Hitler was now getting his newfound support from various middle-class elements who were desperately seeking refuge in the midst of a violent economic storm.

The political platform of the Nazi Party offered solace and hope to clerks and bankrupt businessmen. It called for the abolition of unearned earnings and "interest slavery," the nationalization of all trusts, a dividend system for big business, and the death penalty for loan sharks and profiteers. At the same time, it assured all patriotic Germans that they would break the yoke of the Treaty of Versailles and persecute the Jews, who were stigmatized not only as exploitative capitalists, but also as materialist communists. It should be emphasized that Hitler has been lobbying for this platform over the past few years with minimal response. The Great Depression was the immediate and primary cause of the change in his political fortunes. Until the full impact of this platform was felt, Hitler was seen by most Germans as a talkative and harmless fanatic; when nearly half the workforce was unemployed, he became increasingly A beloved Führer because he provided a scapegoat for their misfortunes and a programme of action for the fulfillment of personal and national aspirations.

Thanks to the September 1930 elections, the Nazi party increased its representation in the National Assembly from 12 to 107, making it the second largest party in the country. This unintended result gradually undermined Germany's parliamentary polity, as it deprived not only the centrist-right coalition that Bruening had desired, but also the centrist-left coalition that had ruled under Miller. . As a result, Brüning had to rely on presidential decree to enact all the necessary regulations for more than two years. The extent of his reliance on Hindenburg was confirmed when he proposed a statute for the decentralization of East Prussian estates; President Hindenburg, himself a Junkers landowner, was adamantly opposed to the statute and forced Bruning in 1932 Resigned in June.

The new chancellor was Franz von Papen, nominally a member of the Centre Party. He was in fact a reactionary aristocrat, aptly described as "a gentle, benevolent, gentle insignificant figure, a brilliantly intelligent fool". The weak coalition government he led had meager support from the National Assembly, so he held new elections in July 1932, hoping to strengthen his position. The Nazis, however, emerged as the biggest winners: their votes soared to 13,799,000, or 87.4 percent of the vote, and their seats soared to 230. Moreover, these advances have been made at the expense of the parties of the right and the centrist, since, compared with 1930, the combined seats of the Socialists and the Communists have actually increased by 2.

Hitler then became the head of the country's largest political party. In negotiations with President Hindenburg, he demanded full executive power. "What do you mean by this request?" asked Hindenburg. Hitler replied, "I simply demanded the same powers that Mussolini exercised after his march into Rome." Hindenburg refused, not impressed by the man he called "the Bohemian corporal." impression. However, the parliamentary system of government does not work at this time. Since neither the Nazis nor the Communists will join a coalition government, it is unlikely that this government will have the support of the majority.

In November 1932, Papen held another election in an attempt to break the deadlock. This time, the Nazis lost 2 million votes and 34 seats in the National Assembly, reducing their number of MPs to 196. While they remain the country's largest party, they can no longer pretend to be the irresistible tide of the future. Indeed, the leaders of the Nazi Party suddenly panicked. Hitler's deputy Josef Goebbels wrote in his diary on December 8, 1932: "The whole organization is extremely depressed. It is impossible to do well without funds. The Führer paced back and forth in the hotel room several times. Hours. Apparently, he was thinking hard. . . . Suddenly he stopped and said, 'If the party breaks down, I will shoot myself immediately.' Terrible threat, extreme depression."

Less than two months later, the suicidal man became Chancellor of Germany. One reason for this astonishing turnaround was that German business leaders were now giving the Nazi Party substantial financial aid, fearing that if the party collapsed, millions of votes might go to the left. On January 4, Hitler met Cologne-based banker Kurt von Schroeder, and since then the "lack of funds" that Goebbels complained about has ceased to be a problem. Another reason was that politics in Berlin at the time were seen as a quagmire of intrigue. Hindenburg was old and frail by this time, and could only work consciously for a few hours a day. He was persuaded to dismiss Papen and appoint Kurt von Schleicher to replace Papen; Schleicher was even more cunning than his predecessor.

Schleicher decided to try a demagogic method. He reversed Pabon cuts to wages and benefits, revived plans to divide East Prussian estates, and, through government-imposed agricultural regulations, set out to investigate illicit profits made by landowners. Landlords and merchants blamed him with hatred and dragged Hindenburg over. Schleicher was vulnerable for the same reason that Bruening and Papen were vulnerable earlier: not being able to form a majority in Congress. On January 28, 1933, Schleicher was forced to resign, and two days later Hitler became chancellor of a coalition cabinet of Nationalists and Nazis.

Within six months, Hitler had organized the whole of Germany according to his ideas about race and leadership. On 5 March, following an unprecedented campaign of propaganda and terrorism, a new National Assembly was elected. The Nazis got 288 seats and 5.5 million votes, but they still accounted for only 44 percent of the vote. When the MPs met, Hitler declared the Communists' seats invalid, and then made a deal with the Catholic Centre Party, which gave him enough votes to pass the Enabling Act on March 23, 1933. The Delegating Act gave him the power to rule by decree for up to four years. But by the summer of 1933, he had virtually eliminated or controlled all independent elements of German life - trade unions, schools, churches, political parties, the medium of communication, the judiciary and the federal states. As early as April 22, 1933, Goebbels wrote in his diary: "Now the power of the Führer is completely dominant in the Cabinet. There will be no more votes. The Führer himself decides everything. Much faster than we dared to hope."

Hitler thus became the master of Germany, and, as he constantly boasted, by legally legal means. The Great Depression made his victory possible, but it was by no means inevitable; this possibility became reality due to a combination of other factors, including Hitler's own talents, aid from various vested interests, and his The lack of vision of the opponents - they underestimated Hitler and failed to unite as the opposition. On August 2, 1934, Hindenburg died, just in time to enable Hitler to combine the powers of president and chancellor into a single person. The following month, at the Nazi Party Congress in Nuremberg, Hitler declared: "The German way of life for the next thousand years has been clearly defined."

British Foreign Secretary Sir Austin Chamberlain said after comparing the international situation in 1932 with that of the Nogano era: I have looked at the world today and compared it with the situation then, and I cannot Not to admit, for some reason, because of something hard to pinpoint, the world is going backwards nearly two years. Countries are not getting closer to each other, not increasing the level of friendship, not moving toward stable peace, but adopting attitudes of suspicion, fear and threats that endanger world peace.

The "something" that Chamberlain could not be sure of was the Great Depression and its various international and domestic effects. The various international agreements of the Locarno era, especially on reparations and war debts, are no longer viable. It soon became apparent that governments, driven to the brink of collapse by a declining economy and mounting unemployment, could no longer deliver on promises made a few years ago.

In July 1931, at the initiative of President Hoover, the great powers agreed to a moratorium on all intergovernmental debt payments. This moratorium showed that there was, in fact, a close link between the various debts and reparations among the Entente, although Hoover repeatedly reiterated that there was no such link. The following summer, at the Lausanne Conference, the great powers, though not in theory but in fact, completely cancelled Germany's war reparations. At the same time, payments to America's war debt were ended, although several token payments were made in subsequent years. So the thorny old problems of reparations and war debt were finally swept away by the economic storm unleashed by the Great Depression.

Another effect of the economic turmoil is the development of local economic nationalism to the point of hampering international relations. Amid the general collapse, countries' self-defense measures have taken the form of higher tariffs, stricter import quotas, settlement agreements, currency control regulations, and bilateral trade agreements. These measures are bound to cause economic friction and political tensions between countries. Various attempts have been made to reverse this trend, but none have been successful. The World Economic Conference held in London in 1933 was a frightening failure, and "economic independence", that is, economic self-sufficiency, gradually became the generally accepted national goal.

Closely related to this is the gradual cessation of attempts at disarmament, giving way to plans for large-scale rearmament. The Disarmament Conference, which began in August 1932, ran on and off for 20 months, but was as ineffective as the Economic Conference. As the 1930s wore on, countries devoted more and more power to rearmament. This trend has proven impossible to stop, as arms manufacturing provides not only imagined security but also employment opportunities. Unemployment in the United States, for example, did not decrease significantly until it began rearmament on the eve of World War II. Likewise, Hitler's massive rearmament program quickly resolved the unprecedented unemployment he faced. It should be soberly recognized that Hitler was most successful in pulling his country out of depression because he was the most thorough in preparing his country for war. In addition, the social devastation of the Great Depression and the accompanying unemployment took a toll on people, so people everywhere welcomed new jobs, even those in military factories. It is probable that no measure could have endeared Hitler to his people as much as the massive rearmament that gave jobs to the desperately unemployed.

The weapons and equipment that were accumulating at this time were bound to be used sooner or later, but there needed to be some reason to use them; "living space" was the most obvious reason. It was a term coined by Hitler, and similar expressions and arguments were used by Mussolini in Italy and by military leaders in Japan. According to this doctrine, unemployment and widespread misery are caused by a lack of living space. A lucky few nations seized all colonies and sparsely populated overseas territories, leaving other nations without the natural resources necessary to sustain their peoples. The obvious way out is expansion, with force if necessary, to correct past injustices. This is the argument used by so-called "poor" countries against "rich" countries.

In view of the fact that the Great Depression devastated Germany, Italy, and Japan, it equally and impartially devastated the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom—a claim that is clearly plausible. However, the idea of living space served to bring the people of "poor" countries together to support the expansionist policies of their respective governments. It also provides an ostensibly moral justification for aggression that publicly declares its purpose to feed the poor and work for the unemployed. In fact, even in "rich" countries, there are some who accept these theoretical explanations and justify the ensuing aggression. Even some Western politicians, reluctant to believe these specious reasonings, sometimes have to turn a blind eye to aggression because of pressing domestic problems. The repeated success of blatant violations of the League of Nations in the mid-1930s was partly due to the overriding domestic problems that Western leaders had to deal with first.

Such was the combination of forces that gave rise to what Chamberlain called "suspiration," "fear," and "regression" in 1932. In the years that followed, these forces completely undermined the reconciliation that had been reached in the 1920s, contributing to crisis after crisis, culminating in World War II.

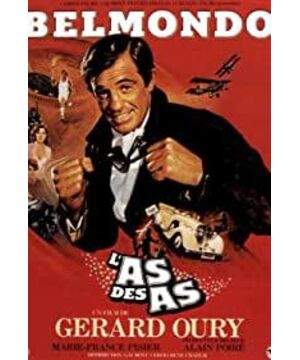

View more about Ace of Aces reviews