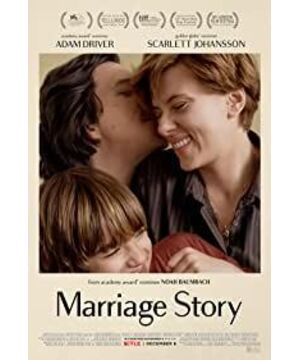

I suddenly want to practice translation, but I am not very skilled, welcome to make suggestions :)

Removed from the homepage of veteran New Yorker film critic AO Scott

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/05/movies/marriage-story-review.html

Dance Me to the End of Love

dance with me to the end of love

Traditionally, a story that ends in matrimony is classified as a comedy. But what about a story that begins with the end of a marriage? Noah Baumbach's tender and stinging new film, “Marriage Story,” doesn't quite answer the question. It's funny and sad, sometimes within a single scene, and it weaves a plot out of the messy collapse of a shared reality, trying to make music out of disharmony. The melody is full of heartbreak, loss and regret, but the song is too beautiful to be entirely melancholy.

Traditionally, a story that ends with a wedding is always classified as a comedy, so how should a story that ends with a marriage be classified? Noah Baumbach's new book "Marriage Life," tender and tingling, doesn't really answer. At the same time hilarious and cheerful, the film is also sentimental, and at times in the same scene, it choreographs its plot in the chaotic collapse of shared reality, trying to find music from dissonance. The melody is full of heartbreak, loss, and regret, but the whole song isn't exactly sad -- just because it's so captivating.

Charlie (Adam Driver) and Nicole (Scarlett Johansson) are an artistic couple living in Brooklyn with their 8-year-old son, Henry (the wonderful, deadpan Azhy Robertson). Both parents work in the theater: Nicole, a former teenage movie star (and a child of Hollywood), is a leading performer in the experimental stage company that Charlie, himself a sometime actor, directs. What we know of their life together is conveyed in an opening montage in which each partner, in turn, lists the things they love about the other. They've compiled these catalogs at the urging of the mediator hired to help them through their separation.

Charlie (Adam Driver) and Nicole (Scarlett Johansson) are a Brooklyn-based artist couple with an eight-year-old son, Henry (the genius Azhy Robertson). Both parents work in theaters: Nicole, a former teenage movie star (the daughter of Hollywood), now starred in experimental theaters run by Charlie, who also sometimes acts himself. In the montage at the beginning of the film, they take turns listing their reasons for loving each other so much that we get a sense of how their lives were together. They hired a marriage counselor to help with the separation crisis, and they collected this kind of love just to meet the counselor's request.

What follows — as an amicable split becomes a shattering rupture, lurching from awkwardness to rage in search of a new equilibrium — is a reversal of Tolstoy's sturdy observation about happy and unhappy families. Happiness is unique, inexpressible, a state that exists outside of narrative . Misery is what makes you just like everyone else.

When an amicable separation turned into a shattered break, and embarrassment turned into rage, the marriage stumbled and found a new balance, but what happened after that reversed Dostoevsky's attitude toward fortunate and unfortunate families. That deep analysis. Happiness is a unique, indescribable state that exists outside the narrative; misfortune will only make you an ordinary person.

This is certainly the perspective of the divorce lawyers who soon replace that hapless mediator. Nicole, who has a role on a television pilot, takes Henry to Los Angeles, where her sister (Merritt Wever), their mother (Julie Hagerty) and Henry's cousins live. This move, which Charlie insists is temporary — “we're a New York family,” he says to anyone who will listen — becomes a point of contention between the spouses and their attorneys. Papers are served. Voices are raised. Henry , whose well-being is supposedly everyone's chief concern, is pulled back and forth, his life wrenched out of sync.

Undoubtedly, the perspective of the hapless marriage counselor was quickly replaced by divorce lawyers. Nicole moves with Henry to Los Angeles, where her sister (Merritt Wever), mother (Julie Hagerty) and several of Henry's cousins live. Although Charlie insisted to everyone who heard the story that the move was temporary -- "We're New York home," the move became a point of contention between the couple and their defense attorneys. Court subpoenas have been issued, and the quarrel has intensified. Henry's happiness should be everyone's main concern, but in the repeated back and forth of his parents, he has been hindered as much as his life.

Nicole and Charlie, onetime creative collaborators, become characters in a drama neither one controls. “We need to tell your story,” says Nora (Laura Dern), Nicole's lawyer. Charlie visits two — a rumpled mensch (Alan Alda) and a shark in a suit (Ray Liotta) — and one of them urges him to “change the narrative.” For both parties (as they are called once their experiences are translated into legalese), this means rewriting a happy-couple past into a history of struggle.

Nicole and Charlie, once brilliant partners, become pitiful characters in a runaway farce. "We have to tell your story," says Nicole's attorney, Nora (Laura Dern). Charlie meets two lawyers, a raunchy decent man (Alan Alda) and a well-dressed liar (Ray Liotta), one of whom urges him to "take control of the story." For both couples (whose experience was translated into legal language when they were arraigned once), it meant a happy past married life being rewritten as a history of hard work.

The most painful parts of “Marriage Story” act out that revisionism, as idiosyncrasies are made to look pathological and mistakes are treated as potential crimes. The German social critic Theodor W. Adorno wrote that “divorce, even between good-natured, amiable, educated people, is apt to stir up a dust-cloud that covers and discolors all it touches,” an insight that Baumbach illustrates with vivid precision. He shows how “the sphere of intimacy” (to continue with Adorno) “is transformed into a malignant poison as soon as the relationship in which it flourished is broken off.”

The most painful aspect of Married Life is that it embodies a kind of revisionism, in which private idiosyncrasies are seen as pathological and minor mistakes are treated as potential crimes. German social critic Theodor Adorno wrote: "Divorce can easily raise a cloud of dust and fade away its color wherever it goes, even for two mild-mannered, approachable, and educated people. ". Baumbach attests to this with vivid precision. He shows how the "realm of intimacy" (continuing Adorno's words) "turns into a poisonous throng—when the love that grows in it is cut off abruptly."

The intimacy doesn't just vanish. At their moment of most intense conflict — when the thin line between love and hate seems to have been irrevocably crossed — Nicole still calls Charlie “honey.” There is still a residue of sweetness between them, which offers hope, not necessarily for reconciliation but for a limit to the damage each will inflict and sustain.

Intimacy doesn't just disappear out of thin air. Even in the heat of the conflict—the irreversible crossing of the line between love and hate—Nicole calls Charlie "baby." There is still a residue of love between them. Although this does not give the inevitable hope of reunion, it is expected to limit the damage caused by each dispute to each other.

What is happening is catastrophic, ridiculous and also — as the lawyers know — perfectly ordinary. Baumbach, exploiting and extending the tremendous talents of his cast, refuses to exaggerate. There are spasms of farce and throbs of melodrama, but they arise within the rhythms of everyday behavior. Which is not to say that Nicole and Charlie are confined to the shabby, somber stagecraft that so often passes for realism. They are large, complicated personalities with professional and emotional lives that fill their days, and the screen, with anxiety , surprise and occasional delight.

The destructive power of all the drama going on is absurd, but also—lawyers know this best—uncommon. Director Baumbach, while doing his best to evoke the immense talent of the actors, refuses to act too exaggeratedly. The film is full of farce-style muscle spasms and literary-film-style throbbing, and this is born out of people's actions in life, showing its proper rhythm. Not that the characters Nicole and Charlie are confined to some stale and dingy stage "art," performing fake realism; they are two important and complex people whose career and Life is full of anxiety, surprises, and occasional pleasures that fill their days together and fill our screens.

Baumbach works to be fair to both of them, and the effort shows. Like his other movies, perhaps even more so, this one feels personal. I don't just mean autobiographical. In a few minutes on Google you can find out about his marriage, his parents, his in-laws and whatever else you want to know. That information only confirms what you have already intuited if you've seen "The Squid and the Whale," "Margot at the Wedding," "While We' re Young” or “The Meyerowitz Stories: New and Selected”: He draws from his own life.

Baumbach tried to treat them both equally, and his efforts were evident. Like his other films, this one—perhaps even more so—is a personal experience. I'm not just referring to its autobiographical nature. You can easily google his marriage, parents, parents-in-law, and everything you need to know. If you've watched "The Squid and the Whale," "Margot at the Wedding," "When You're Young," and "The Meyerowitz Story," then all the information about him online only confirms your intuition: his Creation comes from personal experience.

But you shouldn't expect the picture to be perfectly objective or symmetrical. In some ways, “Marriage Story” is harder on Charlie than on Nicole, underlining his self-absorbed, self-pitying tendencies, but he also occupies the film's sympathetic center of gravity. It understands him better, even as Nicole has plenty of chances to explain herself. She seems to be the one who precipitated the breakup, whose expectations and feelings changed in ways that Charlie struggles to comprehend. He is blind to some of the consequences of his own behavior, which includes cheating on Nicole with a member of the theater company.

However, you cannot expect this cobbled imagination to be completely objective, or to correspond with the facts. In a way, Charlie is worse than Nicole in "Marriage Story," which puts him at the center of the gravitational field of empathy, despite its constant emphasis on his selfish and self-mourning tendencies. This allows him to be better understood, just as Nicole has countless opportunities to justify herself. She seemed to be the one who made the breakup, and her expectations and emotions dominated every aspect, and Charlie struggled to understand and respond. He failed to see the direct consequences of some of his actions, such as cheating with theater members behind Nicole's back.

The infidelity is treated as a sidebar, which isn't entirely convincing. And while “Marriage Story” delves into the tangled thickets of its characters' feelings, it is coy — or maybe just tactful — about their sexual lives, together and apart. Nicole has a moment of lust (following a moment of fury), but Charlie is, libidinally speaking, a closed book.

Less convincingly, the affair was treated as a side issue. Plus, while "Marriage Story" digs deep into the character's emotional intricacies, it takes a coy, or rather slick, approach to the couple's sex life. Nicole has shown lust (after rage), but Charlie, as far as the libido of lust is concerned, can't be seen through.

The complexity of the film's perspective — what Baumbach reveals and what he withholds, how he keeps up with characters whose circumstances are changing rapidly even as they feel like they're stuck — places enormous demands on Driver and Johansson, who are simply extraordinary. They are perfectly matched, which is to say interestingly mismatched, given the trajectory of the story. Each one has a charisma that's a little mysterious, a hint of Cubism in their faces, an undertone of irony in their voices. How could they ever have expected to know each other?

The complexity of the film’s perspective—what Baumbach intends to reveal, what to hide, how he keeps up with the characters when they are trapped and the situation changes rapidly—places high demands on Driver and Johansson, but their The performance is just too good. They're so good together, and based on the story, they'd be interestingly out of touch. Each of them has an extraordinary charisma, a mysterious cubism in their faces and a sarcastic bass in their words. How did the two of them think of getting to know each other in the first place?

One of the morals of this story, chastening but also oddly encouraging, is that we don't ever really know one another, but we're nonetheless obligated to try. Lawyers do it their way, insisting on simple answers to difficult questions. This is the place to note that Alda, Liotta and Dern collectively come close to stealing the movie, in part because they are playing performers fully in their element in ways that Charlie and Nicole are not.

One of the morals of the story, both admonishing and inspiring, is that we never really get to know each other, and yet we have a responsibility to try to do so. Lawyers have their own way of "getting to know" who is litigating, insisting that they answer tough questions with short answers. It should be noted that here Alda, Liotta and Dern are jointly trying to attract the audience's attention, partly because they are acting in their own field, but Nicole and Charlie are not acting.

We sometimes see those two at work — there are some delicious tidbits of backstage comedy, in both New York and Los Angeles — but rarely onstage. There are two important exceptions, moments of theater that use borrowed words and self-conscious artifice to deliver strong doses of unadorned feeling. Both involve songs from Stephen Sondheim's “Company”: “You Could Drive a Person Crazy,” a jaunty complaint about falling for a charming narcissist; and “Being Alive,” a heartfelt lament about being one. That number, sung by Driver near the end of “Marriage Story,” is an anthem of need, building to the shattering realization that “alone is alone, not alive.”

Sometimes we get to see the duo at work—there’s always an anecdote backstage in New York and Los Angeles—but not always on stage. There are two important exceptions to such theater moments, the use of lines and conscious means to express strong, unpolished emotions. Stephen Sondheim's "Companion" is used in both places: "You'll Make People Crazy," a light-hearted complaint about falling in love with a glamorous narcissist; lamentation. Towards the end of the film, the song Driver sings is a paean to mutual need, and he sings all the way to the heartbreaking realization that "loneliness is just loneliness, not living."

That is a bleak conclusion, and it's one that this meticulous and messy movie both acknowledges and resists. Bouncing between two large, opinionated American cities, Charlie and Nicole discover that other people are impossible and indispensable: children, colleagues, in-laws, exes , even sworn officers of the matrimonial bar. Alive is alive, not alone.

This conclusion is a little dark, but it is a point that this chaotic and cautious film has to agree with while refusing to admit it. Tossing between two self-righteous American metropolises, Charlie and Nicole eventually discover that everyone else is so unbearable and so hard to give up: kids, college, in-laws, exes, and even sworn justice in divorce court personnel. To live is to live, you can't just be alone.

View more about Marriage Story reviews