Q: Speaking of the character Yoav in "Synonyms", the child in "The Teacher" is also called Yoav. Are you trying to connect the two films?

Rapid: Let's just say it's the same person -- the kid in "The Teacher" grew up, stopped writing poetry, graduated high school and went to the military, and that's what happened next. But it can also be said that these two characters are people of the same temperament at different ages and in different environments. Imagine that Yoav's decision to never speak Hebrew again in Synonyms is quite dramatic, because he has a talent for the language, but he is now not allowed to use those words himself.

So maybe at 5 he gave up poetry, at 22 he gave up language. These two films are also expressing the mentality of these people: they are engaged in a fierce struggle, a battle against what most people think is normal around them; and as citizens of the world...being in this world means that they are this normal. Part of -- this confusion of consciousness is the sticking point. This war against normality has them turning their backs on themselves, you could say they are trying to cure the same disease.

Q: You used the word "crusade". There are many confrontational scenes in the film, like Yaron harassing subway passengers and Yoav questioning the orchestra members at the end. Why are you designing these plays?

Lapid: I think in both scenes, the protagonist (and the audience) will feel that this confrontation is necessary to reveal the nature of the other side. Yaron is convinced that, deep down, it's business as usual - Europe is still anti-Semitic, and so are the French; behind the rhetoric of universal values and the idea of a republic there is a deep-seated hatred of the Jews, and he's going to expose it with drastic measures. everything. Yoav thinks so to a certain extent, but he cares more about their hypocrisy than anti-Semitism.

Question: Hypocrisy?

Rapide: Yeah, there's a difference between the inside and the outside in the culture. Yoav happened to apply terminology and logic learned in a previous class on values, but dismantled them. In this class, it is the French who judge foreigners, who rate them according to how close they are to themselves: in order to be French, the more "French" you are... the more you deny your previous identity, ideas, the closer you are one step. In a sense, (in the last scene) a foreigner tests the French in a subversive way, separating them from "so-called" objective justice or universal values.

But in both these confrontations, you can feel the desperation, they are some kind of orchestrated action, like a conceptual artist using installation art to reveal something. This confrontation is also a cry of despair from the provocateur. Yaron is somehow lost in the madness. He grew up believing in the idea of either me or him: they are not us because they hate us or want to kill us...in a world of binary opposition. He could no longer accept that it was not so. If he found Europe full of ghosts and ghosts, he would be relieved, but the fact that there are no ghosts and ghosts knocked him down and completely disintegrated everything he believed. He knew exactly what to do if three people shouted "Long live Hitler" to hit him, but he was helpless in the face of normalcy. He fears this European norm. It was a cry of despair for Yoav, who was a "faithful believer" of the norm in Israel.

Q: And one more interesting point, at the very beginning you show that Yoav has nothing. He was naked, very symbolic. He was reborn.

Rapid: He was reborn, like a baby—naked in the water, nothing. In a sense, his fantasies have also come true, if his fantasies are to die symbolically as an Israeli and be reborn as a Frenchman, and not only that, his love in the most "French" Reborn on the bed, a couple from a French movie. As Wilde said, the only thing more disappointing than not living your dreams is living them. (Translator's note: Here Lapid should refer to "There are two tragedies in life, the first is that you can't get what you want, and the second is that you can get what you want.") Ten minutes into the film's opening, he arrived at what he wanted. Where to go: This is his prime, when he opens his eyes and asks, "Is this death?"

Q: It looked like "Christ descended" when the couple lifted him out of the tub. "Circumcised," Emile said, before covering her private parts with a towel.

Rapid: It's for censorship in China (laughs).

Q: Can we read any symbolism from it?

Lapid: Yes, it reminds me of a Renaissance painting I once saw in a religious school in Israel where they covered the exposed parts. I think it's funny Emile they do it, they educate him and try to make him a part of this society; they don't know what to do with his nudity. At the same time, he said he was "circumcised," so even if he died, he was considered a Jew.

Q: Speaking of the couple, Louise Chevillotte starred in Philippe Garrel's Love for a Day. Did you choose her because of that movie?

Rapide: I chose them because I saw their work and thought it was great. The film has an interesting, contradictory relationship with French cinema. While citing French cinema, it confronts French cinema, its "new wave" heritage, contemporary French cinema, and the established way of filming Paris.

From time to time you can see this double process, slapped in the face while applauding. I think there is a certain symbolism in putting these two young actors together - one in the work of the last hero of the new wave (Philippe Garrel, One Day), the other in the most French contemporary director (Arnold Deplechamp's "Three Memories of Youth") - using them in different combinations, different film languages, different mise-en-scene.

Q: Similar to how Yoav uses French...

Rapid: Yes, by absorbing the language he's changing it too. This is also very similar to what Yoav wants to do. On the one hand, he dreams of being the most ordinary French, the most normal French, the most "French" French. On the other hand, he dreamed of becoming an independent man, a foreigner who came to France, became the emperor of France, and changed the French code or system.

In the last scene, when he yells in the hallway, "French people, I'm here to save you, the Republic is falling." He has this fantasy, this madness, not to change France, but to make it back to where it should be. When he shouted "Marseillaise", what he called "Marseillaise" became a revolutionary song again, no longer commonplace and incomprehensible to sing. Suddenly he was like Rouget de Lisle, and the song took on meaning again: the revolutionaries were fighting, with that readiness to be radical, cruel, kill or be killed, like He said to someone in the orchestra, "Come on, fight for your music."

Q: On the other hand, Emile is borrowing stories from the Israelites, just as the teacher in The Teacher borrows poetry from Yoav…

Rapide: When we shoot with the French side, you often get the feeling that they envy your story. This complex relationship is between two cultures, one culture has everything but no real urgency or drama, and the other has nothing but its own pain... Emile is indeed a bit like a kindergarten teacher, She knew poetry well but had no words to express it.

Nadav Rapid

Q: He wants to be Victor Hugo.

Rapide: Exactly. But he has no "Les Miserables" to tell. The only miserable person he knew was "Jan Valjean" (Yoav).

Huang Yue: I have a question about the photography of Synonyms. At the beginning you are already comparing the two ways of shooting. The first scene is very fast, like the first view, and then when Yoav enters the apartment, the camera is still. Is this also an interpretation of French cinema?

Rapid: There's always been a conflict between vibration and stabilization in the film. Vibration contains inner movement, inner storm; it may contain many emotions, such as sadness and pain, but at least it also contains an opportunity for change. And these fixed shots are like... you're born and you die in this big Ottoman apartment.

From this point of view, it is no accident that the film ends with a fixed shot. But in the beginning, Yoav was in and out of the frame, as if trying to get out. From the very beginning it seemed like there was a competition in photography to see who would win in the end, whether it was this vibrating sight, vibrating people, vibrating being, or being fixed. Even naked, he runs in spaces where people don't run; and when he runs, falls, and rises again, he seems to invade this stable space with his active, quivering body.

Q: I have another question about the character of Yaron. Hector's story is central to their friendship. This is also a story that Yoav has especially liked since he was a child. Later in the movie there is a scene where Yaron is dragged behind a car like Hector.

Rapid: To me, it's like unhistorical history. History is not history, this is a very Israeli and possibly contemporary statement: everything is ahistorical, the Bible, the myth, the Holocaust. All of this is really close at hand. You turn your head and you might see the biblical King David sitting in a bar drinking with Jesus. Hector's death in battle is not a historical fact, but the present.

Also, I always said to myself before making this film, to make a historical film in a way that has no sense of history at all. This is also the strength (and weakness) of cinema: it tells the present better than the past and the future. Either way, you have to condense it all down to the here and now.

Q: How did you deal with humor in this film?

Rapid: I think the humor in all of my films is that you find a scene funny, but you don't know if that's what the director intended. You say, "Haha, that's a joke," and then you watch the movie and think, "No, that's pretty serious." I've had this sort of thing in my life a lot, and sometimes I hear someone say something about what it feels like He has a great sense of humour, and then I saw the serious look on his face, so I wasn't sure. It's a kind of disorientation humor.

Q: I noticed that Maren Ade was one of the producers, and Tony Erdman has this unsmiling sense of humor.

Lapid: Serious comments can be more fun than jokes. And the camera doesn't understand these jokes, stupid. There was a scene where several people were fighting at their desks, and it was shot in a very serious, calm, ordinary way, and the camera didn't know what was going on. You want to say, "This is so funny, give me a close-up," but it comes out...like a normal day in the office.

Q: In The Teacher, the camera is mostly placed in the children's position.

Lapid: In general, because this film is mainly about kindergarten people and childhood, at a moment I felt that childhood should not be just a screenwriter's design, but should actually appear on the screen. Shooting this way also affects the way the film captures the gestures and movements of the children. It's no use trying to turn kids into little adults because it just doesn't work.

Second, what's the point of making a movie like this if you're turning kids into unsuccessful adults? At the same time, I don't want to turn my camera to a childish perspective, because I'm not a child. At one point in the film, you feel the tension—the camera follows one logic, the kids follow another, and the result is a fusion of the two strategies. It is also a tension between the filmic object and the filmed.

Q: You often have poetry in your films; in Synonyms, you turned synonyms into poetry. How do you feel about poetry and movies?

Lapid: Obviously, when it comes to poetry and movies, there are always a lot of clichés. For me, whenever there is a tension between high and low, there is a connection to poetry. The craziest thing about poetry is that you can take the everyday words we all use, put them in a different order, and suddenly they become a poem. But still those words you would use in the supermarket.

This also allows poetry to enter a huge field of art, on the one hand it becomes sublime, on the other hand it almost becomes a lifesaver for the pretenders. When I see a painting or hear a Bach work, they use material that I don't have access to, I just listen. But poets (like Celan, Rilke, Rocca) use the exact same words I use every day, so I can say, "What's so great about this?" You use the exact same thing, just a different context. So this fusion of the high and the banal, the high and the low, even the fine and the vulgar, for me, that's what poetry and poetic cinema is all about. It has a tension between art and non-art, like the sky and the sidewalk.

Q: Why did you choose Synonyms as the entry point for the film? Did you sort them on purpose?

Rapide: I just put them in the order I think is right. This is also related to my own experience, when I was learning French to build up my vocabulary, my strategy was to learn the synonyms of each word. But I also have to practice over and over again, otherwise I will forget. Every time I say a word, I say all its synonyms. Each conversation takes hours.

Q: Also like "slam poetry".

Rapid: I want my movies to be like rap music. What I like about rap music is this: Simply put, you need an orchestra or an instrument to make music, which is very complicated, but with rap you can put them behind you and express what you see and think in the most direct way . Like the Lumière Brothers film, the people, the camera...everything is left undisguised, it goes back to its essence. But the rap certainly wasn't that stark, because...Snoop Dogg and Cypress Hill didn't sound the same, so all of a sudden the tone gave the lyrics a new meaning. For me, rap music is also a template.

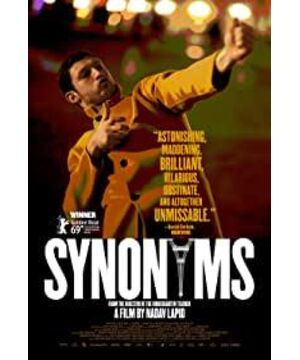

View more about Synonyms reviews