By Stephen Puddicombe (Little White Lies)

Translator: csh

The translation was first published in "Iris"

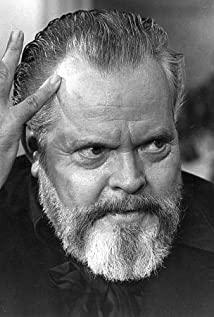

Any art form or film genre, once adopted by Orson Welles, is never what it was. Whether creating radio plays, dramas, documentaries, or Hollywood films, Wells will treat every project in an unreasonable manner, ignoring established rules and using his genius eye to initiate radical innovations that will shred, Rewrite the creative norms for future generations of filmmakers.

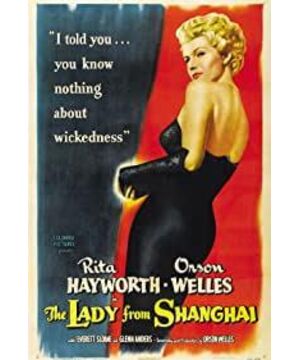

Seventy years ago, he made his unique mark on film noir. The result of all this is "Miss Shanghai," a stylized, disturbing work that, while it's a bit cluttered, we can find a flash of unusual inspiration, as well as many of Welles' most special style logo. Although "film noir" is just a generic label that critics attach to specific films when reviewing film history, we can still find a consensus that it can be used to describe a certain type of film Crime Movies: There are often established narrative elements in this type of work, the morality of the male protagonist should be questioned, the women are just as untrustworthy as they are, they are usually seductive and only mean trouble. Film noir also contains plot twists and turns that spiral slowly into the dark center of a gloomy city.

In Wells' "Miss Shanghai," he parodied and subverted a series of norms, which also included the above-mentioned elements. At the beginning of the film, what caught the audience's attention was how unusual the voiceover was. First, Wells — who is a director, but also an actor, plays the leading man as a sailor — adopts a suspiciously Irish accent. First-person narration is often present in film noir, but Wells' accent creates a level of absurdity, especially with the likes of Humphrey Bogart, Robert Mitchum, Sterling Hayden, and others. Compared to a hoarse, deep voice.

It's not just the voice of the narrator that brings about this weird comical feeling - Michael's tone and tone are also unusually funny and cheerful, with a certain sarcasm in his voice as he recalls his story. , he was laughing at his own stupidity. "When I start making a fool of myself," begins the narration, "there's almost nothing to stop me." In fact, throughout the rest of the film, he continues to insert his own comments accusing himself of being stupid. .

The stupidity mentioned above refers mainly to the following passage: Michael falls into the traps that are usually set for the male protagonist in film noir. After meeting the femme fatale Elsa Bannister, played by Rita Hayworth, he admitted: "From then on, I didn't use my head very much, except to miss her." Indeed. , his desire drives his rash decision to accompany her and her husband Arthur (Everett Sloan) on a boat tour of Mexico. He then slides further into the abyss as he agrees to participate in a criminal scheme to help Arthur's eccentric business partner Grisby (Glen Anders) fake his own death - a decision that makes him Inevitably, he was involved with the villain, whom he had previously compared with utter disgust to a pack of bloodthirsty sharks.

All of these elements are pretty standard for a film noir. But what makes "Miss Shanghai" different is that it has a subtle, ironic detachment and a subversive quality to it, as if everything was a little off track. We can hear traditional orchestral music, but juxtaposed with percussive Latin music and Chinese opera music. Grisby is evil, but Wells presents it in a deranged, grotesque, even dramatic way. There is a courtroom scene in the film where Michael and the others are tried in court, but the scene feels like a complete farce. Wells had Arthur serve as both defense attorney and witness, and at one point, even cross-examined himself. Meanwhile, jurors are laughing, sneezing, and babbling about their opinions and leading the trial to wrong verdicts.

The film's famous, incomprehensible plot is itself a witty joke. Wells imitated the labyrinthine narratives found in film noirs, such as The Nightmare (1946) and Beyond the Vortex (1947). The whole story is constantly intersecting in a two-line narrative, sometimes taking abrupt turns, shifting places between New York, Mexico and finally San Francisco, which creates a bewildering look and feel. Towards the end of the film, Michael's revealing voiceover ties all these loose branches together. Wells also teases the complexity by having his characters come together in a fun and spooky building, and he literally falls off a slide when he reveals he's the "substitute" ( Translator's Note: "The Fall Guy" is literally "the fall guy").

At the bottom of the slide is a mirror labyrinth, the film's famous final climactic scene. (But sadly, the scene was also brutally cut, like so many other parts of the film.) It was a shocking spectacle, an expressionist shootout in which the shooter had to Their targets were distinguished from dozens of reflected images. At the same time, the scene can also be seen as a terrifying visual metaphor, the hero of film noir trying to reconcile his position in a skewed world. It's a fitting, chaotic ending for the most vertiginous movie of its kind. It's a noir film, but Wells, as always, has produced something different.

View more about The Lady from Shanghai reviews